We are delighted to host Yemisi Aribisala, the author of Longthroat Memoirs: Soup, Sex, and Nigerian Tastebuds. Brittle Paper is the first stop in her week-long blog tour publicizing her amazing new book of essay about Nigerian food and culinary culture.

As promised, we have an exclusive peek into the book. Scroll down to read the short excerpt, in which Aribisala makes a surprising discovery in a Calabar market. You’ll get a taste of Aribisala’s unmatched skill at making Nigerian food something quite wondrous.

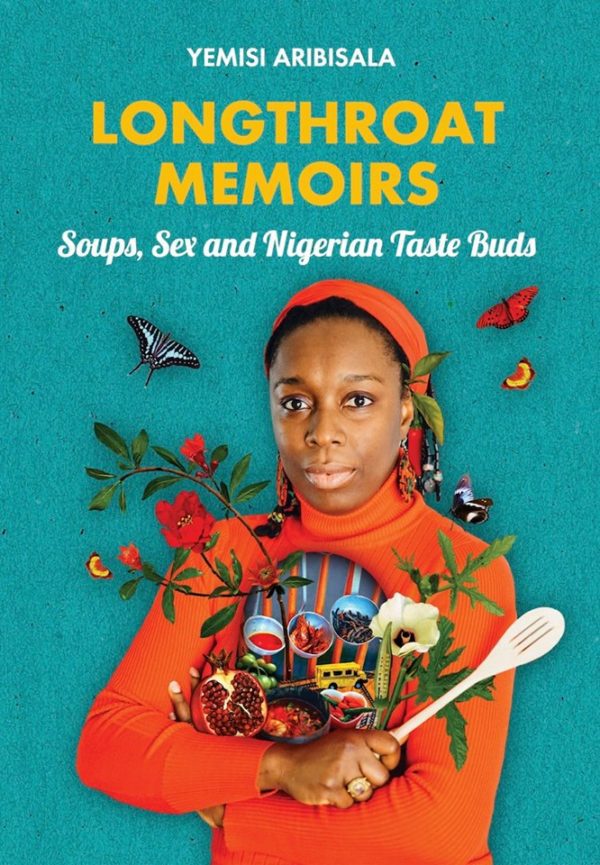

You’ve read the excerpt and the synopsis of the book and have seen the book cover (above). It’s time to write any questions or comments you might have in the comment section. Feel free to ask questions or simply leave a comment about anything—Nigerian food, recipes, ingredients, food writing, essay writing, publishing, etc. Aribisala will respond to you as best as she can.

Okay, let’s go!

Synopsis:

Longthroat Memoirs presents a sumptuous menu of essays about Nigerian food, lovingly presented by the nation’s top epicurean writer. As well as a mouth-watering appraisal of the cultural politics and erotics of Nigerian cuisine, it is also a series of love letters to the Nigerian palate. From innovations in soup, fish as aphrodisiac and the powerful seductions of the yam, Longthroat Memoirs examines the complexities, the peculiarities, the meticulousness, and the tactility of Nigerian food. Nigeria has a strong culture of oral storytelling, of myth creation, of imaginative traversing of worlds. Longthroat Memoirs collates some of those stories into an irresistible soup-pot, expressed in the flawless love language of appetite and nourishment. A sensuous testament on why, when and how Nigerians eat the food they love to eat; this book is a welcome addition to the global dining table of ideas.

Excerpt:

How to Make Meat

I am at the old woman’s condiment stall, buying uyayak pods (tetrapleura tetraptera) with bitter kolas to keep snakes out of the house, when something behind her catches my eye.

‘What is that?’ I ask.

‘Usu,’ she responds absentmindedly, gathering the pods into a bag.

Why do I bother asking these sort of questions when I always get those sorts of answers? ‘What is Usu?’

‘Usu … Usu!’ She turns around to reach for the soil-covered, nodular tuber, and my eyes grow round from shock.

‘Where is this from?’ I ask, attempting to keep my voice from expressing excitement. She is putting all my things in one place and can’t seem to do that and hold a conversation at the same time. She stops what she is doing, catches her breath and explains that it is like a mushroom. You take a bit of it, put it back in the ground and it grows. ‘Just like that!’

I know she doesn’t mean ‘just like that’. I’m staring at her with amazement because of the striking similarity between what she is nonchalantly holding in her hand and what those odd white men on the BBC Lifestyle channel rapturously refer to as a truffle: a very expensive mushroom that you cannot put back in the ground to grow just like that. Of course, if I start to ramble on about wild fungi and how one fist-size truffle can cost over a thousand euros, and how it is documented that you absolutely cannot commercially grow truffles, she would forevermore treat me like a market-crazewoman, the worst sort of crazeperson, so I keep my cool, buy a small, cleaned piece and ask her what she would cook with it, if she will cook it. I am already treading dangerous ground standing around asking questions.

She says she will. She won’t infuse oil with it or frugally shred it on top of her meal. We are in a market in Calabar but there is no market for this usu; there is no need to think about whether or not it is commercially growable or if it is the most expensive food in the world. It is just a mushroom that Igbos eat, so the mental partitioning that the locals apply to her wares when they approach her stall has relegated the usu’s value to next to nothing. Achi, ofo and ogbono have more market value than the usu.

In Calabar, it is not unusual to run into world-renowned delicacies pretending to be nobodies: strawberries up on the plateau at the Obudu Cattle Ranch; sole peddled out of old basins on Hawkins Street; lime-green and red rambutans hawked on little girls’ heads in May. And now usu, which might be the tartufi bianchi, one of the most expensive, luxurious foods in the world. Perhaps I should say nothing about it so that Calabar is not overrun by trifolau with specially trained pigs hunting for truffles. When she says you can put the mushroom back in the ground to grow, she is talking like a genuine trifolau with knowledge of a special grove in a secret place. The place where the usu will grow is not anyplace that you know or can reach, so what value is that information to you? Nothing. She recommends combining usu with egusi to create a meat substitute. A beloved, triumphant meat substitute, not one in the fashion of tofu-pretending-to-be-chicken, or those vegetarian sausages you might see in La Pointe supermarket that have a sort of I’m-sorry-I’m-not-meat air about them. I am amazed by this suggestion because we like to stereotype ourselves as unrepentant carnivores who can’t bear the sight of our meals sans animal flesh. Yet here is a local substitute that we would happily eat in soup.

Hand-shelled egusi is ground with the usu in a blender and then pounded in a hand mortar until the oil begins to separate from the seeds.. The successful pounding and the separation of the oil leaves a smooth beige mound. This processing is the same as pounding egusi for the ntutulikpo soup but with the added dimension of taste and texture from the usu. Salt, pepper and onions are added if the eater desires. A large pot of water is kept boiling on the hob. The mixture is cut into equal sized pieces, shaped as desired and cooked in the boiling water until the meaty texture is attained. This boiling typically takes thirty to forty-five minutes.

There is something about boiling that doesn’t quite agree with me: I keep thinking of all the flavour and nutrients being drowned. The egusi and usu mixture should be steamed in thaumatococcus leaves, but boiling is the only way to create the texture of meat, the only way to create something that can texturally hold its own in a pot of soup as a meat substitute.

Beautiful, right?

Now write any questions or comments you might have on the comment section.

Again, join us in giving Aribisala a warm welcome!

PS: Where to get the book:

Lagos: Patabah bookstore, Shoprite Suru-Lere, Quintessence Ikoyi, Jazzhole Ikoyi, Glendora Ikeja City Mall etc.

Abuja: the Cassava Republic Bookshop stores it and they are at 62B arts and crafts Village, opposite Sheraton.

If you live in the US, the Uk, and so on, go HERE.

Yemisi Aribisala November 29, 2016 14:14

Dear Tolulope, how well I know that look! I remember once standing in one of those aisles in Calabar Marian market and discussing with another woman and saying by-the-way that I wasn't too hot on white smoked crayfish and the way it overwhelmed soup with its aroma. The silence, the looks, the disdain from all around me. It was as if I had sworn at the top of my voice. So many I wouldn't say overlooked ingredients, but ones that I had never heard of or didn't imagine I would find in local markets: Baskets of Rambutans for example, even poured out on the floor in front of Marian market, so cheap I stood staring and thinking of how you found them in supermarkets in the UK sold six for 2 plus pounds, carefully arranged in styrofoam, covered with cling film: Oyster mushrooms - a basket stood in the market one day and people walked past and stopped and complimented it as if it was some kind of visiting monarch: Mushrooms wrapped in banana leaf and kept near wood fires for days on end until its Umami is deep and its texture is like meat: Desiccated paw-paw, left to ooze milk and dry in the sun then stored for soup: Black dried sprouts also for cooking soup in place of meat. When black peppers (uziza) are harvested in Calabar they are a beautiful red colour -fire engine red- and you can imagine them arranged on a stall table. I remember seeing large coral coloured smoked crayfish - the really big ones Delta people call Isa Okpotokpo, or the Yoruba call Ede pupa; so expertly treated that they looked fresh. Their shells were tender as if the crayfish had been steamed. The aroma on them was unbelievable. Only once did I see them throughout my stay in Calabar and they were incredibly expensive. So many delicacies... many many of them that people couldn't even give me a name for. One of my all time favourite discoveries is the "country onion", a beige hard kernel that the Cameroonians use for cooking beans. The delicious savouriness that it gives when ground and added to cooking is something quite special.