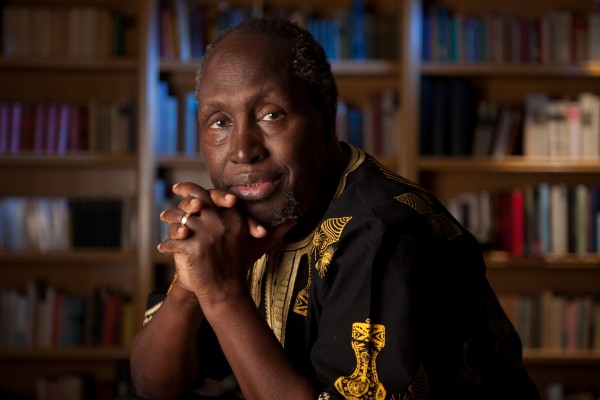

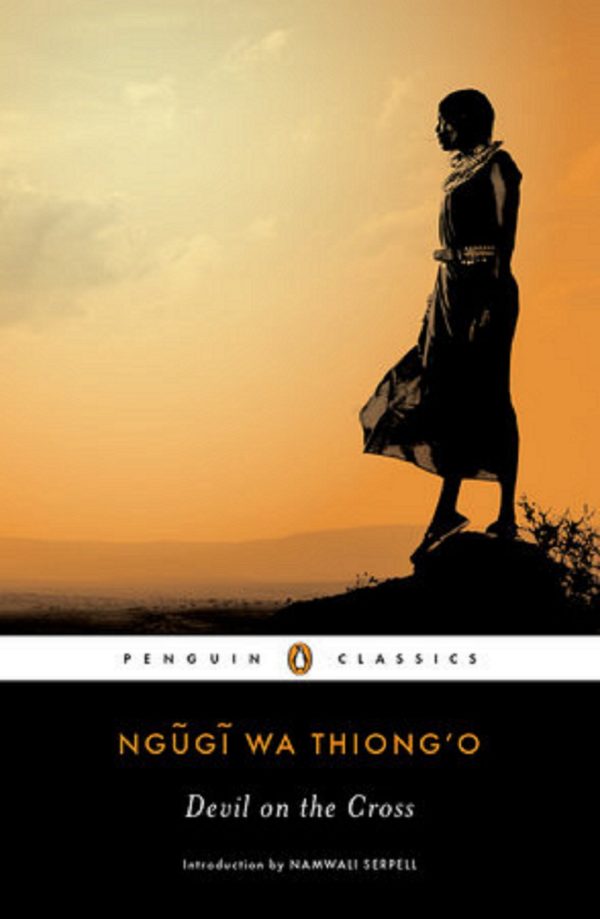

Thirty-seven years after it was first published, Ngugi’s Devil on the Cross has a new edition from Penguin Classics, with an introduction by the 2015 Caine Prize winner Namwali Serpell. Part of this introduction, titled “Kenya in Another Tongue,” is published in The New York Review of Books and traces both Ngugi’s political awareness and his ideological evolution that saw him declare the need to have African stories written primarily in African languages.

The new edition of Devil on the Cross has generated much discussion, most notably Tope Folarin’s Los Angeles Review essay in which he discusses matatu, dreams, Ngugi himself and—wait for it—Serena Williams. Serpell’s introduction dwells more on the personal life of one of our greatest writers.

Here is an excerpt of Namwali Serpell’s introduction.

On December 30, 1977, the Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was arrested. In the middle of the night, bulky Land Rovers and flashing police cars stormed his yard in Limuru, Kenya. They were brimming with men armed with pistols, rifles, and machine guns. As the officers searched his library, Ngũgĩ asked if he was under arrest. The officers said no. He was simply being asked to accompany them to the police station, where he would be given the task of cataloging the books and pamphlets the officers were plucking from his shelves: titles by Marx, Engels, Lenin, and so on. They also confiscated about twenty-five copies of Ngũgĩ’s own play, cowritten in Gĩkũyũ with Ngũgĩ wa Mĩriĩ, entitled Ngaahika Ndeenda, or I Will Marry When I Want.

The two writers and the locals of a village called Kamĩrĩĩthũ had staged the play in a community-built open-air theater. Its five-month run had been immensely popular, drawing large crowds from afar. But on November 16, 1977, the Ministry of Housing and Social Services had essentially banned further performances of the play by withdrawing the license for any public gathering at the Kamĩrĩĩthũ Community Education and Cultural Centre. This, Ngũgĩ assumed, was why, when he reached the police station, he was handed a detainment order signed by the then Vice President of Kenya, Daniel arap Moi. In the early morning hours of December 31, 1977, Ngũgĩ was driven to Kamĩtĩ Maximum Security Prison in Nairobi. He would be kept there without a trial for nearly a year.

Ngũgĩ has detailed his prison experiences in Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary. He lost his name—he became detainee K6,77—and lived in Cell 16 in a block with a handful of other political prisoners. For a time, they were given only one hour of light a day. They took it in a bare compound where they chatted and played chess and sought prophecies in the pages of the Koran or the obscure flights of doves. Mostly, Ngũgĩ says, they moved in “erratic, aimless circles and wanderings, going everywhere and nowhere…. The compound used to be for the mentally deranged convicts before it was put to better use as a cage for ‘the politically deranged.’” For many prisoners, reading and writing were palliative. Ngũgĩ notes with amusement that he had always found the idea of toilet paper manuscripts “romantic and unreal.” But if the coarse toilet paper at Kamĩtĩ was meant to be punishing, “what was bad for the body was good for the pen.” Ngũgĩ wrote the notes that became Detained on that toilet paper. He also wrote the classic novel Devil on the Cross, which has been published in a new edition by Penguin.

Caitaani Mũtharabainĩ, or Devil on the Cross, came into being at a crossroads in Ngũgĩ’s life and in the life of the country that he loved enough to criticize. In 1952, when the Mau Mau Rebellion began—members of the largely Gĩkũyũ Kenya Land and Freedom Army revolted against British rule, sometimes with extreme acts of violence—the British declared a State of Emergency. By the time Ngũgĩ was fourteen years old, the colonial regime had taken over Kenya’s national schools. English, already widely used to enforce submission to colonialism and conversion to Christianity, became the language of instruction. This meant that young Kenyans were introduced to classics of English literature like Shakespeare’s plays. But they were also forcibly exposed to the incongruous, racist, and mediocre works of colonial writers like Elspeth Huxley.

In his well-known collection of essays Decolonising the Mind (1986), Ngũgĩ provides telling anecdotes about his childhood inculcation in linguistic imperialism. Refusal or inability to speak English was punished in both corporal and psychological fashion: strokes of the cane upon the buttocks; metal plates around the neck saying I AM STUPID or I AM A DONKEY. Each time a student spoke in a mother tongue, they would receive a button; they would hand it on when they overheard the next culprit; at the end of the day, the students would sing the names of whoever had passed them the button; all the offenders would then be punished. In this way, cultural shame was both internalized and self-regulating.

Ngũgĩ had grown up speaking Gĩkũyũ at home. This was how he first encountered stories, riddles, proverbs, and what he calls the “music of language.” He was the son of a farmer and the brother of a political dissident. His brother, a member of the Mau Mau movement, was killed; another brother, deaf and mute, was shot during the State of Emergency; Ngũgĩ’s mother was held in solitary confinement for three months. Both of these facts—his class upbringing and his family’s politics—served as marks against him, but Ngũgĩ managed to gain admission to Makerere University College, in Kampala, Uganda, in 1959. There, in 1962, he attended “A Conference of African Writers of English Expression,” a historic meeting of black writers that included Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, and Es’kia Mphahlele. Ngũgĩ, who at the time went by James Ngugi, had written but not yet published his early novels Weep Not, Child and A River Between. Ngũgĩ was stirred by the debates at the conference. The very first item on the agenda was “What is African literature?” This zombie question—still often raised, never fully dead—naturally led to a discussion of language. Why was most so-called African literature written in European languages?

These questions haunted Ngũgĩ. But he continued to write and publish novels in English, including A Grain of Wheat (1967), and to teach in English as an associate professor and chairman of the literature department at Nairobi. Ten years later, an old woman in Kamĩrĩĩthũ, a village near the suburb where he lived, asked Ngũgĩ to help rehabilitate the local cultural center. Only then did Ngũgĩ begin to write in Gĩkũyũ, which is spoken by only about 22 percent of Kenyans and is read by far fewer. The play that sparked his arrest was also his reawakening to his mother tongue. Ngũgĩ’s theater initiative at Kamĩrĩĩthũ was registered as a self-help project with the Department of Community Development of the Ministry of Housing and Social Services. The form of the play—which incorporated Gĩkũyũ song, dance, and folklore—and its staging in a community-built theater seemed to suit the new government’s aim to promote Kenya’s culture and history. But its substance—its vehement Marxist critique of that government and what Ngũgĩ called its “neocolonial” regime of cynical and capitalistic oppression—was deemed inflammatory and he was arrested. Already in prison for writing a play in his mother tongue, Ngũgĩ decided to write a novel in Gĩkũyũ instead.

Read Namwali Serpell’s “Kenya in Another Tongue” in The New York Review of Books.

Buy the new 2017 edition of Devil on the Cross on Amazon.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions