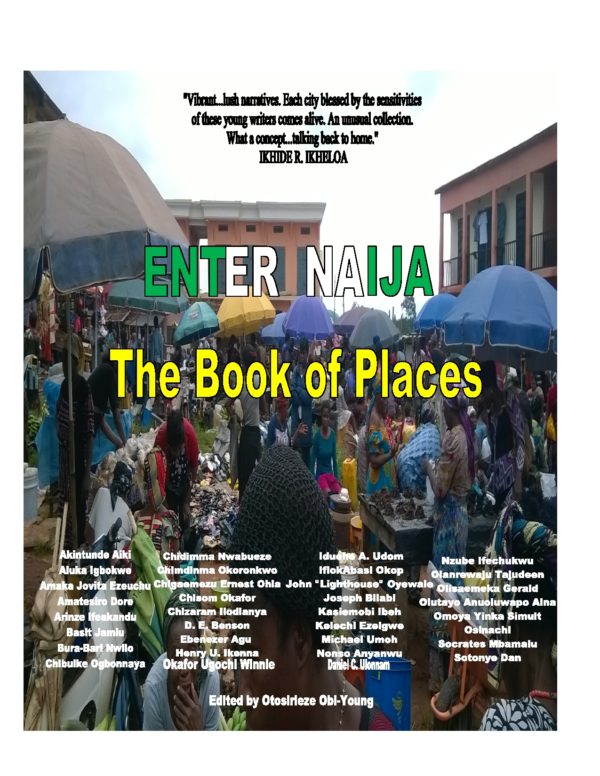

In October 2016, we published Enter Naija: The Book of Places, an anthology of creative nonfiction, photography, poetry, digital art, fiction and commentary on Nigerian cities, designed to mark the country’s 56th Independence anniversary. Featuring 35 writers and visual artists, the anthology is edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young and introduced by Ikhide R. Ikheloa, and is the first in the Art Naija Series. Ahead of the publication of the series’ second anthology, Work Naija: The Book of Vocations, 2012 Caine Prize winner Rotimi Babatunde, who wrote the introduction, shares with us a new essay inspired by the anthology.

Read below.

***

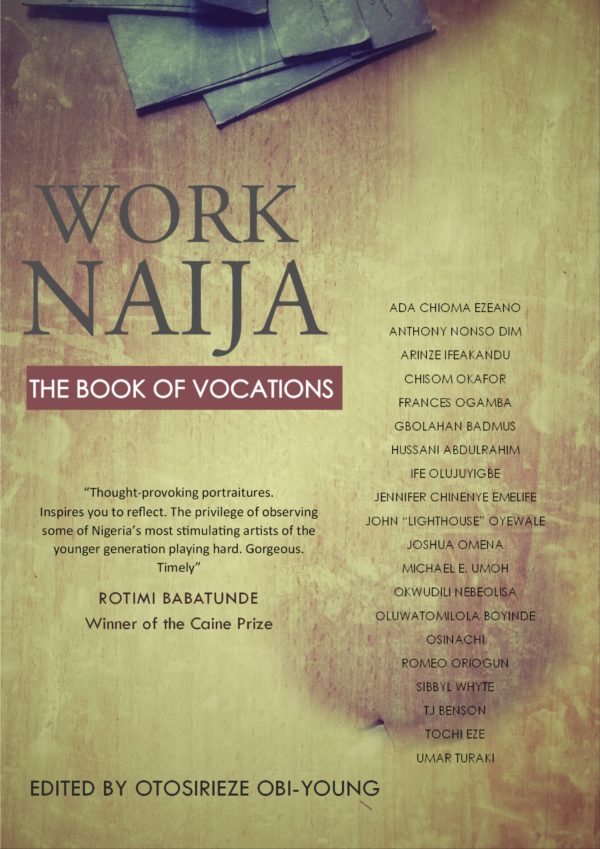

Not only does Work Naija: The Book of Vocations, edited by Otosirieze Obi-Young, make you engage afresh with the occupations addressed by its contributors, it also inspires you to reflect on the very nature of work.

Work, like piety, has long been championed as a divine duty, though that duty has needed to be fulfilled more by common folk than by the privileged. Illustration of that can be found in “The Labours of the Months” gallery of the medieval illuminated manuscript Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, commissioned by John, Duke of Berry, and mostly executed by the Limbourg brothers. On the gorgeous vellum pages of that calendar cycle, peasants are shown dutifully tilling the earth and shearing sheep, harvesting grapes in September and shivering before a niggardly fire in the wintery chill of February. But the Duke of Berry and other royals are only seen cavorting in the vicinity of their numerous chateaux and revelling in the blood sport of falconry and exchanging lavish gifts on New Year’s Eve. Very rich hours, indeed—until the plague, apparently, came in 1416, and death, without discrimination, swept away the art-collecting Duke and many of the peasants he considered his and the artistic geniuses that were the Limbourg brothers, leaving unfinished the illuminated book of hours that connected them all.

The affinity between work and piety was recognized as far back as antiquity by Hesiod. He said in Works and Days, “Both gods and men are angry with a man who lives idle, for in nature he is like the stingless drones who waste the labour of the bees, eating without working.” That Hellenic sentiment is shared by diverse societies across time and space. The apala bard Haruna Ishola begins his song “Oníṣẹ́ Ńṣiṣẹ́” with this line: “The worker is up and about, but the indolent sleeps on, behaving like a king”. That mockery is in line with this proverb from Haruna’s Yoruba culture: “The sluggard says that on the day Death comes, happiness will be his. But Death replies that he’ll delay his coming to compound the sluggard’s misery.” In the sixth century, Pope Gregory I enshrined sloth, which inevitably broadened beyond its initial emphasis on the spiritual, among the Seven Deadly Sins. And several centuries later, Dante, in the Divine Comedy, imagined shirkers like the Abbot of St Zeno being compelled to run in penance around the Terrace of Sloth, recounting the deeds of the diligent like a playlist on repeat.

Not even ostensibly secular societies have found it unbecoming to participate in the consecration of hard work. The Soviet Union, as if run by a politburo of pious red Calvinists, turned the champion miner Alexey Stakhanov, despite the queries raised about his feats, into an icon of national veneration. And in 1964 the Soviets put the future Nobel Prize in Literature winner Joseph Brodsky on a show trial and sentenced him to five years of forced labour for the crime of “social parasitism” (defined by Article 209 of the Criminal Code as “evading socially useful work and leading an antisocial and parasitic way of life”). The Nazis also invented a similar category of criminality. They condemned thousands, including people of Romani ethnicity, to hard labour in concentration camps after labelling them arbeitsscheu. Workshy. And it must not be forgotten that the stereotyping of people of non-European descent as lazy was one of the pretexts for colonialism.

In the face of work’s widespread valorisation, the question needs to be asked: Beyond possibly increasing the chances of basic subsistence, what percentage of the diligent does hard work lift from one economic class into another? Or to put the same question, using Nigerian Pidgin, bluntly: Who work help?

In an attempt to answer that question, a 2015 study of the Pew Charitable Trusts, “Economic Mobility in the United States”, concludes, “The analysis makes it clear that children born into different economic circumstances can expect very distinct economic futures. The degree to which family advantage is transmitted suggests that opportunities for economic success are very unequally distributed. Although no one would be surprised that children from higher-income families enjoy some advantages, this report reveals them to be dramatic.” The same study states that “not only are the earnings of men higher than those of women at each level of parental income, but the average IGE [intergenerational elasticity] for women is more than 40 percent lower than that for men. It follows that, although men and women both benefit from being born into higher-income families, men secure this advantage disproportionately via their own earnings.”

That’s not all. A 2016 survey by the Pew Research Center on the economic realities of black and white households in the United States makes this grim observation: “In 2013, the most recent year available, the median net worth of households headed by whites was roughly 13 times that of black households.” It also notes that “even among adults with a bachelor’s degree, blacks earned significantly less than whites”.

These studies show that other factors are more critical to the attainment of comfort and affluence than hard work. (That dreadful sound you are hearing is nothing strange: just class, gender and racial discrimination hammering nails into the coffin of the American Dream—that myth of equal opportunity.) Numerous studies in other countries have, adjusting for context, arrived at findings that agree with the ones above. In the light of that knowledge, one cannot but think that the tragedy of Okonkwo in Chinua Achebe’s trailblazing Things Fall Apart would have been averted if the character had realised that neither hard work nor masculine bravado could have ameliorated his true impoverishment: the second-class status foisted upon him by the Europeans who reduced him and his people to mere subjects of the British Empire.

“Leisure is better than occupation and is its end,” wrote Aristotle in Book VIII of his Politics. But if, for the reasons outlined above, hard work does not guarantee the attainment of leisure, we must shed a tear or two for the much-loved, hardworking characters in literature, belief and folklore. John Henry, whose victory over the white man’s steam drill threw no spanner in the wheels of his country’s racist political and economic machinery. Long-suffering Joe Gargery, blackened by the forge, henpecked by the combustible Mrs Joe and abandoned by his food-wolfing pal Pip in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations. Martha of Bethany, patron saint of servants and cooks, put down by Christ with words that were little different in essence from the ones he directed at the devil: “Man shall not live by bread alone.” And, of course, Animal Farm’s Boxer, who confronted every challenge with the motto “I will work harder”. Ultimately, after working himself into terminal exhaustion, Napoleon and his porcine gang promptly dispatched Boxer to the knacker’s in exchange, hints the novel, for a case of whisky.

As we empathise with these hardworking heroes of literature, simultaneously celebrating its true rebels—the loafers and wastrels who subvert the suspect burgher morality of hard work with their delinquency and mischievousness—is necessary. Notable among them is Oblomov, the eponymous antihero of Ivan Goncharov’s 19th-century novel, who spends his days lying in bed and bickering with Zakhar, his likewise apathetic manservant. “Lying down was not for Oblomov a necessity, as it is for a sick man or for a man who is sleepy; or a matter of chance, as it is for a man who is tired; or a pleasure, as it is for a lazy man: it was his normal condition,” said the narrator in Goncharov’s novel.

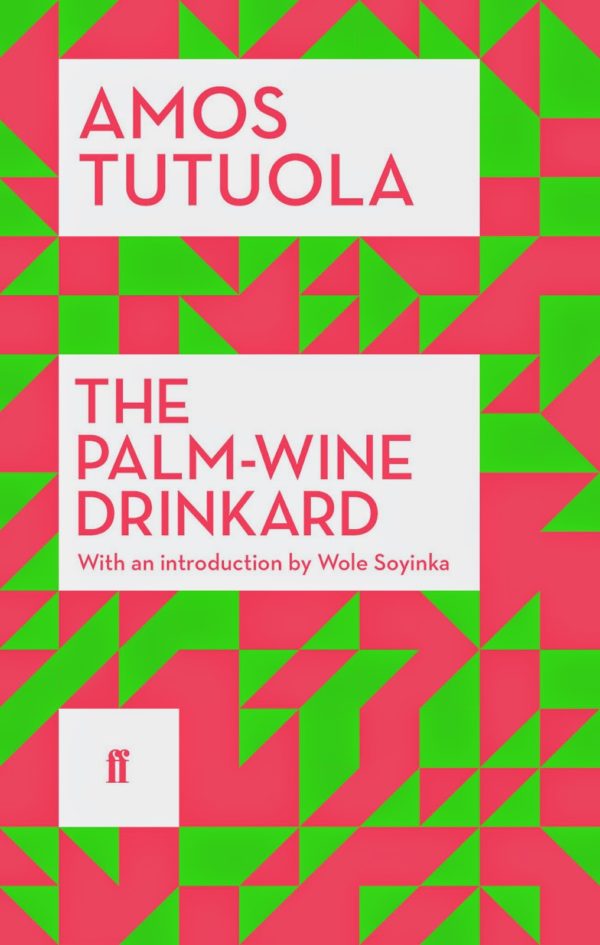

And there is Nkem Nwankwo’s Danda, one of the great comic characters in literature, whose notoriety as an akalogholi, a good-for-nothing, earned him the nickname Rain. His father Araba had charted a respectable path for him, but Danda, typically dressed in a cloak adorned with tinkling bells, preferred playing the flute and dancing, flouting communal taboos and getting drunk on palm wine. Talking of palm wine drinking, mention must be made of literature’s foremost aficionado of that art, Amos Tutuola’s the Palm-Wine Drinkard. Here is the Drinkard telling us, in his inimitable voice, about his lifelong aversion to hard work: “I was a palm-wine drinkard since I was a boy of ten years of age. I had no other work more than to drink palm-wine in my life…. My father got eight children and I was the eldest among them, all the rest were hard workers, but I myself was an expert palm-wine drinkard. I was drinking palm-wine from morning till night and from night till morning.”

Among literature’s famous slackers, Unoka, Okonkwo’s father in Things Fall Apart, deserves special acknowledgement if class is taken into consideration. Oblomov, Danda and the Palm-Wine Drinkard had the considerable wealth of their different families as safety nets, but Unoka did not have such resources to call upon: he had to survive by guile and debt (as demonstrated by his encounter with his creditor Okoye) since the poetry of his musicianship could not put food on his table. Unoka’s daring rejection of the goals prescribed for men by his society—numerous yam barns, wives and titles—is anti-materialist rebellion of the purest kind.

Let us imagine Oblomov—who does not even move from his bed to his dressing table until well into the novel that has him as its central character—arriving in Dante’s afterlife and being told to explain why he shouldn’t be made to undergo the dizzying penance of running round and round the Terrace of Sloth. And let us also imagine Unoka docked before Mme Saveleva, the judge in Joseph Brodsky’s 1964 trial, attempting to defend himself against the charge of social parasitism. The excerpts below from the proceedings of that trial, transcribed by the brave Frida Vigdorova and translated by Michael R. Katz, leave no doubt about what Unoka’s fate in Mme Saveleva’s court would have been.

JUDGE: What do you do for a living?

BRODSKY: I write poetry. I translate. I suppose. . .

JUDGE: Never mind what you “suppose”. Stand up properly. Don’t lean against the wall. Look at the court. Answer the court properly. (To me [Vigdorova]) Stop taking notes immediately! Or else—I’ll have you thrown out of the courtroom. (To Brodsky) Do you have a regular job?

BRODSKY: I thought this was a regular job.

JUDGE: Answer correctly!

BRODSKY: I was writing poems. I thought they’d be published. I suppose . . .

JUDGE: We’re not interested in what you “suppose”. Tell us why you weren’t working.

BRODSKY: I had contracts with a publisher.

JUDGE: Did you have enough contracts to earn a living? List them: with whom, what dates, and for what sums of money?

BRODSKY: I don’t remember exactly. My lawyer has all the contracts.

JUDGE: I’m asking you.

Mme Saveleva—hardworking judge that she is—harasses Brodsky some more, demanding for details of his employment history. And then she goes for the jugular.

JUDGE: And, in general, what is your specific occupation?

BRODSKY: Poet. Poet-translator.

JUDGE: And who said you’re a poet? Who ranked you among poets?

BRODSKY: No one. (Unsolicited) Who ranked me as a member of the human race?

JUDGE: Did you study for this?

BRODSKY: Study for what?

JUDGE: To become a poet. Did you attend some university where people are trained . . . where they’re taught . . .

BRODSKY: I didn’t think it was a matter of education.

JUDGE: How, then?

BRODSKY: I think that . . . (perplexed) it comes from God . . . .

Judge Saveleva would have found Unoka guilty of the allegation levelled against Brodsky, just as Oblomov would have been subjected to the same penance the Abbot of St Zeno had to endure in Purgatory. Evidently, sloth and social parasitism, conceptualised centuries apart, are just two sides of a coin: the devil always invents crimes for idle hands. But Brodsky was busy writing poetry, Oblomov reflecting on existence as if he were a precursor to Paul Valéry’s Monsieur Teste, Unoka playing the flute, Danda causing mischief, and the Palm-wine Drinkard traversing the realms of the living, the dead and the unborn in search of his tapster. So they were employed in activity of some kind. Rather than convicting the aforementioned of sloth or social parasitism, a judge with a penchant for fine—even if ultimately immaterial—linguistic distinctions might find it more fitting to convict them all of another charge: play.

Play, like sloth, is oppositional to work. However, unlike sloth, play and work connote engagement in activity; the key difference is that play, unlike work, is activity directed towards ends that are not utilitarian. Play is an adventure undertaken for its own sake, without any functional purpose and without material profit as an objective. Play seeks to contribute nothing to the GDP of any country. Play, as conceived here, is not, as some might presume, a rest or holiday from work. Aristotle, in Politics, considers such interludes mere “medicine for the ills of work”, not “leisure”. Play, even if it sounds less pejorative than sloth or social parasitism, is broadly synonymous with them in the transgressive sense that Chinua Achebe, in his essay “Work and Play in Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard”, brilliantly captures thus: the raising of “pleasure to the status of work or occupation”.

If play is transgression, many of the best minds in history stand guilty of it. The modernist artist Paul Klee found nothing more worthwhile to do with his time than dreaming of “taking a line for a walk” in his bid, like Kandinsky’s, to wrench out novel realities from the abstract. Benjamin Franklin’s fooling around with a kid’s kite in the storm and Luigi Galvani’s gross play in the lab with frogs’ legs were so economically worthless that the story had to be invented of England’s future Prime Minister William Gladstone asking Michael Faraday, decades after Franklin and Galvani had died, if electricity had any value. The daunting wordplay and formal ambition of James Joyce’s Ulysses had attenuated the novel’s commercial prospects even before its sexual frankness, by the standards of the day, caused it to be banned in several countries, including the United States where the Postal Department routinely burnt copies of the book. And Bernhard Riemann’s thesis on the geometry of higher-dimensional spaces was so devoid of practical value at the time of its formulation that it could have been the rumbling described in this line from traditional Yoruba poetry: “All to no purpose is the rumbling among the elephant-grass bushes.”

Ironically, it is the very purposelessness of play that enables it to enrich our world in ways that transcend the quotidian. In “Work and Play in Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard”, Chinua Achebe’s earlier-mentioned laudatory essay on Tutuola’s novel, Achebe says that the Drinkard’s “refusal to work cannot be a simple ‘self-regarding act’ but is a social and moral offence of colossal consequence”. Achebe goes on to say that, after the novel’s opening sentences, the Drinkard “proceeds to spend the rest of the book on the punishment he undergoes in atonement for his offence and then a fairly brief coda on his restoration”. But the Drinkard’s journey in search of his dead tapster reads more coherently as an extension of the Drinkard’s commitment to play—even a celebration of it—rather than as a “punishment” for his “offence”. The novel provides no evidence that the Drinkard’s journey to the Deads’ Town reformed him into a conscientious worker. After his return from the journey, the Drinkard says, “I sent for 200 kegs of palm-wine and drank it with my old friends as before I left home.” A few pages later, he adds, “I had become the greatest man in my town and I did no other work than to command the egg to produce food and drinks.” The Drinkard’s “restoration” advanced by Achebe is not vindicated by Tutuola’s novel.

Without the Drinkard’s devotedness to the “offence” of play, he would not have embarked on the adventure that enriched him with marvels like the kind Faithful Mother, the red inhabitants of the Red Town, the Spirit of Prey with its mercury-coloured eyes, and the 400 dead babies marching towards the Deads’ Town—experiences that the conventional lives of his seven hardworking siblings could never have thrown up. The Greek poet C.P Cavafy’s sings about the beauties of such adventures in his “Ithaka”: “May there be many a summer morning when,/ with what pleasure, what joy,/ you come into harbours seen for the first time;/…./Ithaka gave you the marvellous journey./Without her you would not have set out.”

The benefits of play, though, are not only intangible. Because play’s free-spirited explorations lead to “harbours seen for the first time”, it often lays the foundation for the creation of material benefits that those who dedicate themselves to it cannot envisage. Paul Klee could not have foreseen that his ruminations on line and colour—which formed the bedrock of his pedagogy at the Bauhaus—and the equally rarefied meditations of such colleagues of his like Kandinsky would have an influence so ubiquitous on the design of buildings, furniture and industrial products around us that we have almost stopped noticing it. Nor could Joyce have anticipated the huge tourist draw Bloomsday would become in Dublin and other cities around the world. Or Galvani and Franklin that their messing around with frogs’ legs and kites, respectively, will one-day usher in our electricity-dependent world. (This, apocryphally, was Faraday’s response to Gladstone’s question about the usefulness of electricity: “Why, sir, there is every probability that you will soon be able to tax it.”) And Riemann could not have predicted that his seemingly redundant conceptualisation of the geometric properties of spaces unfamiliar to human reality will not just remain a mathematical curiosity but will, decades later, become crucial to the emergence of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity—a gravitational model of the universe that makes possible the existence of the GPS satellites that navigate our planes and cars and make location-based services possible on our smartphones. All work and no play makes the world a stagnant place. Playing hard turns out not to be as useless as it might appear.

Work Naija: The Book of Vocations gives us the privilege of observing some of Nigeria’s most stimulating writers, artists and photographers of the younger generation playing hard with the theme of hard work. The publication of the anthology is timely: in Nigeria and around the world, emerging realities are currently destabilising traditional assumptions about the connection between work and income. As the rapid advances being made in the field of robotics continue to imbue the long-deferred nightmare of the Luddites with contemporary relevance, the prospect that intelligent machines, working more efficiently and at cheaper costs, will soon make a wide variety of professions extinct has led to calls in many countries for the introduction of a universal basic income, to be paid by the government to all citizens. And in Nigeria, a freer press and more vigorous citizen journalism, deploying the new tools provided by information technology, have bared the extraordinary dimensions of corruption by public office holders, initiating a crisis of confidence in the populace about the hitherto sacrosanct belief in the correlation between work and wealth. That eroding confidence in the connection between both is being undermined even further by prosperity preachers, whose message is premised on the logic of divorcing wealth from work and linking wealth with divine grace, aided by “seed sowing”. Let somebody shout hallelujah.

Work Naija: The Book of Vocations contributes to these national and international conversations in direct and oblique ways. The anthology is gorgeous, like the Limbourg brothers’ Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry; in contrast, though, Work Naija: The Book of Vocations brings to bear on the discourse of work critical perspectives that are absent in the medieval volume.

In the manner of all great adventures, Work Naija: The Book of Vocations enriches us with many memorable encounters in the course of its unfolding: Chisom Okafor’s stunning, masterly poem on chefs and their “food-universe” of the kitchen; Ada Chioma Ezeano and Joshua Omena’s thought-provoking portraitures of commercial sex workers and their patrons; Ife Olujuyigbe’s droll insights on the salon habits of hairdressers; and Otosirieze Obi-Young’s autobiographical exploration of the fine qualities that distinguish barbers from one another. There is also the bold iconography of flattened shapes and vivid colours Osinachi deploys in his artworks to capture the realities of musicians, churches, red-light districts, nomads and undertakers; Frances Ogamba’s touching depiction of the quiet dignity of dumpsite scavengers; Anthony Nonso Dim’s take on Roman Catholic clergy and their parishioners, with its startling ending; John “Lighthouse” Oyewale’s learned investigation of the ways photographers see, concretised with metaphors from the animal world; and Michael E. Umoh’s spotlighting of the self-confidence of tricycle drivers and akara sellers.

Look out for TJ Benson’s celebratory, expressive photographs of working women; Tochi Eze’s illumination of the hidden lives of kiosk owners; Jennifer Emelife’s frank piece on society’s unrealistic expectations of teachers; Gbolahan Badmus’ heart-breaking story on the travails of a job hunter; fishermen and their enchantment with waters in Abdulrahim Hussani’s poem; and the sacrament of maternal love in Romeo Oriogun’s contribution, which draws correspondences between the Crucifixion and the daily sacrifices hawkers make for their families. And also check out the fascinating teasing-out of parallels between beggars, motorpark preachers and politicians in Umar Turaki’s reflections; Arinze Ifeakandu’s nuanced, ambivalent take on priests, the liturgy, and the luminous music of the church; Oluwatomilola Boyinde’s compelling black-and-white photographs of workers persevering in a time of economic downturn; and Sibbyl Whyte’s witty imagining of the career progression of prosperity preachers.

More could be said about these artists and their contributions to the anthology, but what’s more delightful than an adventure directly experienced? Reader, wouldn’t you rather wish to set out on the journey into Work Naija: The Book of Vocations yourself?

**************

About the Author:

Rotimi Babatunde is a Nigerian writer and playwright. In 2012, he won the Caine Prize for his short story “Bombay’s Republic.” In April 2014, he was named in the Hay Festival’s Africa39 project as one of the 39 Sub-Saharan African writers under the age of 40 with the potential and the talent to define the trends of the region. In 2015, his short story “The Collected Tricks of Houdini” was longlisted for the Sunday Times EFG Private Bank Short Story Award. His plays have been broadcast on the BBC World Service and presented at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, the Swedish National Touring Theatre, and the Halcyon Theatre, Chicago. He is also a winner of BBC World Service’s Meridian Tragic Love Story Competition as well as the AWF Cyprian Ekwensi Prize for Short Stories.

Rotimi Babatunde is a Nigerian writer and playwright. In 2012, he won the Caine Prize for his short story “Bombay’s Republic.” In April 2014, he was named in the Hay Festival’s Africa39 project as one of the 39 Sub-Saharan African writers under the age of 40 with the potential and the talent to define the trends of the region. In 2015, his short story “The Collected Tricks of Houdini” was longlisted for the Sunday Times EFG Private Bank Short Story Award. His plays have been broadcast on the BBC World Service and presented at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, the Swedish National Touring Theatre, and the Halcyon Theatre, Chicago. He is also a winner of BBC World Service’s Meridian Tragic Love Story Competition as well as the AWF Cyprian Ekwensi Prize for Short Stories.

Simeon Mpamugoh June 28, 2017 13:09

A good effort. Keep it on.