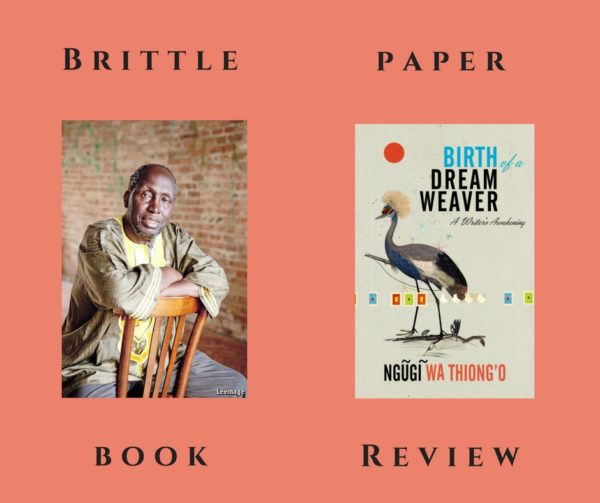

Title: Birth of a Dream Weaver: A Writer’s Awakening

Author: Ngugi wa Thiong’o

Publisher: The New Press

Year: 2016

Where to buy: Amazon

***

“We did not know (that) we lived in Paradise… This paradise could only refer to the Makerere of the 1950s and early 1960s. It was not just its location on a hill that faced other hills with poetic-sounding names like Rubaga and Namirembe, on which stood cathedrals or the Lubiri Palace or the Kasubi Royal Tombs.”

In the fifties and sixties, some of the first set of educated East African students found themselves in Makerere University, Uganda, in pursuit of education. Many of them had come from neighboring Kenya where colonial structures, attitudes, gentrification, and oppression had repulsed and confined them, and where they were treated like second class citizens. In Uganda, they had their first experience of real freedom in an environment that offered a semblance of equality for the black students, opportunity for their dreams, and freedom from the strictures that colonial Kenya placed on their creative imagination.

One of those students was James Ngugi (later, Ngugi wa Thiong’o), who left his home country in 1959. In his new memoir Birth of a Dream Weaver: A Writer’s Awakening, the now world-famous author of many novels documents these times with both nostalgia and pragmatism, with both a rose-eyed celebration of what made the time magical, and a clear-eyed appreciation of the complexities that also attended it. Through his eyes, we experience the colonial East Africa and the author’s own creative development first as a playwright, then as a novelist, and briefly as a journalist.

East Africa of the late fifties was both a latent paradise and a swamp filled with undesirable elements. The teachers and professors that made an impression on the young Ngugi and his many contemporaries were both smart hardworking British civil servants and sometimes haughty condescending closet racists unimpressed by their students cockiness. Through literature, in one case with the famous Karen Blixen, locals are portrayed as simpletons, comparable only to animals in their thought process, capability, and in some cases embrace of death. When fifteen men were bludgeoned to death at the Hola Camp in the hands of colonial policemen, their deaths were widely ascribed (by the British perpetrators) to African ritual self-sacrifice, a type of behavior common among animals involving choosing death over indignity or compromise. If the victims could be portrayed as a people with such extreme ritualistic practices, then the perpetrators could get away with many atrocities.

In another instance, during an Economics class, one Dr. Cyril Ehnlich spent the first twenty minutes of every lecture telling the students how “intellectually poor” they were, and warning them against being bigheaded. “You think you are very intelligent”, he would say “just because you have come to Makerere? You think you know everything just because of setting foot in a college? You know nothing!” Another professor from Ngugi’s school had published a book in the United Kingdom in which he

told hilarious stories of his African students who would never answer a straight question with a straight answer. Asked about that bird on the tree, they would talk about a tree on a hill near their home. It was his way of saying that logic and rationality were alien to the African mind. His students, who had worshipped him as this free, liberal, broadminded thinker and writer, with a strong liking for Africa and Africans, were pained and furious when they read how Foster had seen them. They had hugged him as a fellow human; he had embraced them as black objects of his colonial anthropological gaze.

Many authors of his generation have documented their times during these crucial period of modern African life. Chinua Achebe’s There Was a Country (2012), and The Education of a British-Protected Child (2009) come easily to mind, as do Wọlé Ṣóyínká’s Aké: Years of Childhood (1981) and Ibàdàn: The Penkelemes Years (1994). Even Ngugi himself, in earlier memoirs of his childhood, approached many of these events in different ways. The first in the series was Dreams in a Time of War (2010) followed by In the House of the Interpreter (2012), each dealing with a different part of his youth and his brother’s participation in the Mau Mau rebellion.

In each work, like in this one, the lookback isn’t always an unbiased recollection of innocence, combining a subtle longing for the utopia that this past represented with the contrast it provides to the ailing present. And in the case of this third memoir, it also sets record straight on perceived misinformations from the past, particularly about the role of the British in colonial Africa. It also attempted redemption. At the beginning of the book, the writer insists that we call the Mau Mau whose rebellion against British rule cost his uncle his freedom, by its rightful name: “Land and Freedom Army (LFA)”.

The memoir also dwelt a lot on the progress of the young Ngugi’s literary development. His first short story “The Fig Tree” was written to cover up a lie he had told a respected senior student so as to create a good first impression that he was a writer of fiction. The result was a disaster, which improved over time until the work was good enough to appear in the student publication Penpoint in December 1960 when he was 22.

His first novel, first titled “Wrestling with God,” and changed to “The Black Messiah” before being published as The River Between, was written because of the motivation that fifty British pounds offered, from a literary competition administered by the East African Literature Bureau. Against the background of a changing time, we watch as the writer was born, through trial and error, strokes of luck, curiosity, and hard work. His short journalistic career also featured interesting episodes, including one in which he was almost murdered by security guards of a politician after being mistaken for a spy.

Ngugi’s participation in the famous 1962 Conference of African Writers of English Expression held in Makerere was noted in all its significance to the affirmation of the author’s value as a writer and intellectual, all the more notable, perhaps, because he was just a second-year student at that university when he was invited to hobnob with the prominent and best writers around the continent.

Whatever prompted the invitation and the venue, it was thrilling when June 1962 came and I found myself among the big names of the time, which included Ezekiel Mphahlele, the main organizer, and Bloke Modisane, Lewis Nkosi, and Arthur Maimane—all South Africans in exile; Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, Christopher Okigbo, J.P. Clark, and Donatus Nwoga, all from Nigeria; Kofi Awoonor (then going under the name Kofi Awoonor-Williams) of Ghana; and our East African contingent of Grace Ogot, Rebecca Njau, and three Penpoint writers, Jonathan Kariara, John Nagenda, and me. Rajat Neogy and his Transition were very much present: it was as if the magazine and the conference were born of the same moment of East Africa in transition and needed each other. From the Caribbean came Arthur Drayton; and from the United States, Langston Hughes, who had recently published Ask Your Mama, and Saunders Redding, then a prominent African American critic.

It was in this gathering that the seeds of Ngugi’s rebellion against the use of English as a medium of African literature were sown, among others.

It does seem, at times, that literary gymnastics is relegated in favor of detailed recollection in this book, with diligent documentation of minor and relevant scenes and scenarios from the author’s childhood enriching the book more than mere stylistics. The overlay of barely subdued anger at the injustice of the colonial experiment is one of the book’s most visible, ubiquitous, themes. In one notable scene at the beginning of the book, a play that the author (then a student) had written was prevented from being staged at the National Theatre in Kampala because in it a British district officer was depicted to have raped an African rebel’s wife. “He can’t do that,” the British Council had opined, bringing colonial politics and the British sense of self in the world to bear on an artistic expression that, certainly, had roots in fact. And for that, the work is both a valuable addition to the canon of pre- and post-colonial narratives of early African writers in English (slightly ironic, since Ngugi’s primary language of literature today is Gikuyu) and an important historical document.

Frightening to think that some of the angrier parts of the author’s life haven’t even been written about yet.

Rating: 5/5

**************

About the Author:

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s work has appeared in Aké Review, Brittle Paper, International Literary Quarterly, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, and recently in Literary Wonderlands, an anthology edited by Laura Miller. He is the winner of the Premio Ostana “Special Prize” 2016 (awarded in Ostana, Cuneo, Italy) for his work in indigenous language advocacy.

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s work has appeared in Aké Review, Brittle Paper, International Literary Quarterly, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, and recently in Literary Wonderlands, an anthology edited by Laura Miller. He is the winner of the Premio Ostana “Special Prize” 2016 (awarded in Ostana, Cuneo, Italy) for his work in indigenous language advocacy.

Lucky Ukperi June 26, 2017 08:33

This is an interesting review. Ngugi wa Thiong'O remains a pioneer whose works would always open up the vista on (post) colonial relationships.