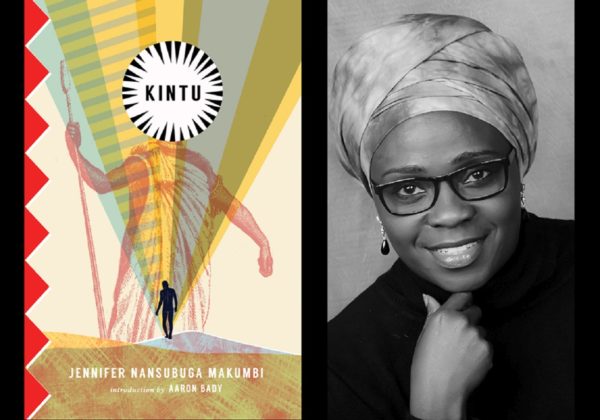

Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi recently had a banging interview with The Los Angeles Review of Books. Her novel Kintu, which won the Kwani? Manuscript Project Award in 2014 and was longlisted for the 2016 Etisalat Prize, has drawn praise. Publishers Weekly called it “A masterpiece of cultural memory…elegantly poised on the crossroads of tradition and modernity.” Library Journal describes it as “Reminiscent of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.” Book Riot called it a “passionate, original, and sharply observed” book that “decenters colonialism and makes Ugandan experience primary.” The book has also earned praised from such names as Maaza Mengiste, Ellah Allfrey, and Aaron Bady who hailed it as “the Great Ugandan Novel.”

This recent interview was conducted by the journalist and writer Alexia Underwood. In it, she made strong comments on homosexuality, feminism and men, Idi Amin and Islam in Uganda, patronising publishers, her next book, and expats. Here are excerpts below.

On homosexuality:

I also wanted to talk about homosexuality, because Uganda is perceived as the most homophobic country in the world, because of the bill [the Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Act, 2014] that was passed. There is an idea that homosexuality came with colonization, and that before that, Africans never engaged with homosexuality. I thought, let’s go back to the past and see. It wasn’t homosexuality that Europe brought, it was homophobia.

On feminism and men:

We have failed to see that the patriarchy also oppresses men, that there is oppression sometimes in privilege. I thought that I can’t start my feminist writing before I address this problem. So this is why I looked at Kintu, the patriarch, as oppressed in a way, especially in the arena of marriage. He’s forced to marry a twin sister that he didn’t want at all. And then, every other day someone is bringing him a virgin or someone is pushing a woman on him and saying, you’re a chief, you should have lots of women because it makes you look like a big man. But he doesn’t want them. And unfortunately, his wife has bought into the whole patriarchal concept and is a very good wife, and she allocates all the women into different regions, of the districts, and he would visit each one of them and spend a week with them and even when he can’t, when he says he’s physically exhausted, she will find him potions. People did not see this as oppression because men perform it, but actually, it’s repression. Another character is Kanani, who has been eating bad food for 40 years because in Buganda, men don’t go in the kitchen. He cannot talk about it because he will undermine his wife. I thought that these things would start a conversation. I mean, feminism in Uganda is still a very middle-class thing—working-class women are not buying into it. Why? I don’t think feminism is complete if it’s not looking at how men could be repressed or oppressed by the patriarchy as well.

On Idi Amin and Islam:

Idi Amin is referred to as a monster. When we talk about our monster in Uganda, that’s fine with me, but when I came out to the West and the West was talking about Idi Amin in ways that were uncomplicated, unproblematized, I stepped back—hang on a minute. For example, I was aware that when Amin came into power, Muslims were far behind Christians in terms of education, wealth. They were not allowed to come to school. If they wanted to join schools they had to be baptized, and Muslims didn’t have their own schools. In the ’70s they were only allowed to do a few jobs, like be butchers or drivers. Then Amin came along and said we’re going to start schools for Muslims. He also allowed an Islamic university in Uganda, and I went to that Islamic university, though I’m a Christian, and this is how I discovered the Islamic history in Uganda.

On patronising publishers:

I remember that when I took the book back home, there was a 14-year-old girl who picked it up and read it in two days. When she finished, she came to me and gave me back the book, and said, “When is the next one?” It wasn’t like, “Oh, I loved it,” or anything like that, she just asked, “When is the next one?” just in case I thought I’d written a fantastic book. I thought back on the British publishers telling me that the British would not understand the book because it’s too difficult, and I looked at this 14-year-old, and thought, god, how patronizing can they be.

On expats and her next book:

I’ve finished a second novel, but I’m working on a collection of short stories at the moment. They’re all about Ugandan experiences in Manchester. I know we would usually say migrant stories, but I’m moving away from that and using the term expat experiences, because I’ve noticed that when the British are talking about their immigrants in Europe who are now being affected by Brexit, they don’t talk about them as immigrants, they call them expats.

Read the full interview HERE

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions