One day, when he was a child, Níyì Ọ̀ṣúndáre’s father called him into the living room to present a gift he had brought for him from Lagos. In Ìkẹ́rẹ́ Èkìtì at this time in pre-independence Nigeria, much of what now defines “enlightenment” was limited to big cities and not generally accessible to all parts of the country.

What his father had bought for his son demanding this intimate interaction in his living room, however, was not a nifty gadget or an electronic device. It was a pen.

“I have brought this for you to use when you have advanced in your education,” the father said. “I do not know how to use it, but I know its power. I use the hoe to scratch the earth for a living; but you will use this pen as your own tool. The way I see the world today, the future belongs to those who are able to scribble black things on a white surface.”

And with that, a book, and the trajectory of the enchanted life of one of Africa’s most prominent published poets began. The book is Niyi Osundare: A Literary Biography written by Sule E. Egya, a poet and literary scholar. The event referenced in the first chapter of the book was necessary to ground the reader in the time and situation of Professor Ọ̀ṣúndáre’s early beginnings, and also in the historical foregrounding of pre-independence Nigeria, Ìkẹ̀rẹ́ Èkìtì in particular, and the poet’s own peculiar upbringing.

Professor Níyì Ọ̀ṣúndáre is today one of Africa’s most recognizable writers, whose life and work bestride decades of creative output in poetry, drama, literary scholarship, and teaching. His is known as the “people’s poet” (defined as one whose work was found to be more accessible as contrasted with the Nigerian poets of earlier generation, Sóyínká, Okigbo, etc, who were deemed to be more obscurantist) has endured, and earned him a niche in the second generation of Nigerian writers as a distinct and delightful voice. He was educated at the University of Ìbàdàn for his bachelors, the University of Leeds for his master’s and York University, Canada, for his Ph.D. He was the Head of the Department of English at the University of Ìbàdàn from 1993 to 1997 and a professor of English at the University of New Orleans since 1997.

When I first met him in the flesh as a student in the Faculty of Arts in the University of Ìbàdàn in the early 2000, his occasional presence as a visiting professor always brought color and excitement to the environment. His reputation as one of the most recognizable members of the faculty had preceded him. He taught a third-year level course in poetry at the Department of English, but not as a full-time member of staff, though I didn’t know that at the time. He came in during the summer and disappeared for the rest of the term. This scarcity further elevated the value of the class he taught and had qualified students scrambling to attend. When I was in my second year and I learnt that it was going to be his final year of teaching in the university, I started attending his classes, even though I wasn’t qualified to earn credits for my work. It was to the professor’s credit and unconventional nature that he never kicked me out.

The biography better situates the reason for his presence on campus during these times in appropriate context. He had transferred from the university to New Orleans in 1997 due to a personal family emergency he discussed further in a recent interview. But he came around to teach every year in Ibadan because of his commitment to the students and to the institution. At close range, he confirmed that commitment, occasionally bringing other writers from around the country to speak with the students. His unconventional nature was evident when, one day when the classroom didn’t feel conducive enough to learn because of heat, he took the class out to a spot in the faculty quadrangle, under the open skies.

Those who have known or read or learnt from this writer and poet and have wondered why there hasn’t been any detailed or comprehensive account of his life, either by the poet himself or by anyone close to him, will no longer have to. As a writer known mostly for his poetry, penning an autobiography might have come across as incongruous with an image of a modest and usually self-effacing man whose passion lay in his work and not in personal aggrandisement (Egya reports that Ọ̀ṣúndáre turned down the Commissioner for Education position from his state government in 1988 and a honorary chieftaincy title from his home town a year later). But in the hands of a competent third-person narrator, in a work of careful and diligent scholarship, we have a comprehensive entry point into the life of the poet, his early influences and affiliations, family life, his published work, criticism of his work, and other notable events in his life.

It turns out that, along with having earned a place as one of the continent’s most enduring poetic voices, Níyì Ọ̀ṣúndáre has also lived an enchated life. “Farmer-born, peasant-bred” is one of the most recognizable descriptors he has used to describe his life. But that says little of the journey he has taken from humble beginnings as a child of Ọ̀ṣun in the forties to become the winner of the NOMA Award for Publishing, the Nigerian National Merit Award for Academic Excellence, the Commonwealth Poetry Prize, and other numerous honours across the world. From being one of the first graduates from his hometown to attend a university, he became a professor of English at the University of Ìbàdàn (in 1989) and an important social commentator who used satire through poetry to address contemporary issues.

His caustic tongue was eventually to prove problematic for the powers that be. After receiving a Commonwealth Poetry Prize in the UK, he was targeted for murder, likely by the Nigerian military regime. One evening in January 1987, while he was walking around the university premises with a friend, he was attacked by unknown men who, having at first confused as to what dangerous weapon to attack him with, settled on an axe with which they hacked his head. He lived to tell the tale, though with a concussion that took months in the hospital to heal. As one whose primary medium of artistic interface with his world is poetry, his response came in the form of a poetry collection Moonsongs (1988), described as “a product of intense therapeutic concentration” and has became one of his most critically praised work, feted for its “inward poetic journey” and “level of technical excellence”.

Another notable brush with death he would face came in 2005 when he was trapped for days in the attic of his own house when the Hurricane Katrina swept through New Orleans. He had taken a job at the University of New Orleans after leaving the University of Ìbàdàn. And due to some scheduling issues, he found himself trapped at home alone with his wife when the levee broke and Lake Pontchartrain poured out its contents, swallowing up the city and displacing its inhabitants. The account, detailed in Chapter 8, takes the reader suspensefully through the horrors and aftermath of the hurricane. The poet-professor had become homeless and faceless, with no identification, job, or housing. He lived in tents and shelters, relying on the goodwill of strangers and a traumatized country.

One of the biggest gaps in contemporary narratives of first and second generation writers from Nigeria – especially those who have spent years living and working abroad – is the full accounting of their lives away from home. Except in a few cases (see: America Their America, You Must Set Forth At Dawn, Never Look an American in the Eye, and Buchi Emecheta), the perception has taken hold that the sojourn of these writers in the new world have been anything but eventful. But how could this be? Could a country as rich and culturally diverse as America (and other Western countries where they have taken residence) be unstimulating for creative contact? Unlikely. What seems a better explanation is that many writers had simply sealed up their “escape” with a bow of silence, keeping only the distant homeland in the center of their creative ferment. In this work, Egya pull up the curtain, gently revealing what is, expectedly, a human tale of triumph. The experience of surviving a hurricane as powerful as Katrina seemed, at the end of his telling, as terrifying as one might expect. But Osundare went through it, and lived to pay homage in his later collection A City Without People: Katrina Poems (2011).

One benefit of reading nonfiction is the pleasure of a casual dive into fascinating historical events with the assurance of veracity and depth. This is where the strength of this narrative is most evident. Who was Ọ̀ṣúndáre as a child? What kind of events influenced him to follow the path that led him here as one of the continent’s most visible, most anthologized, and respected poetic voice? What other things about his personal or professional life are relevant enough to be documented for those interested in learning about him? In this work, the balance is properly weighted, featuring an academic exercise that carefully curates and situates the writer’s work, influences, and criticisms, as guides in a respectful stroll through other consequential events around his life. As Prof Oyèníyì Okùnoyè says in the blurb, Sule Egya “brings the skills of the storyteller and the scholar to bear on his recreation of the Ọ̀súndáre’s story.”. It is a work of literary criticism of Ọ̀ṣúndáre’s literary ouvre, primarily, against the background of the events that influenced them.

There will be a perception, from those who do not share the love and admiration that the author and many of his readers have for the accomplished poet, that the biographer became too deferential at times to be an unbiased raconteur. A sentence like “he is the quintessential man who cannot keep silent in the face of tyranny”(298) will come across as almost an obsequious oversimplification. The life and work of Níyì Ọ̀ṣúndáre speak for themselves as a testament to diligence, integrity, hard work, artistic competence, and political consciousness. But he was never known primarily as a human rights activist.

Still, this very important attempt at putting Ọ̀ṣúndáre’s story at the disposal of readers is a worthwhile effort, situating him in context of the Nigerian socio-political landscape and within world literature. In ten chapters and 334 pages, Egya has discharged that intention well, perhaps even more notably for its (relative) timeliness. The poet turned seventy earlier this year, still wielding the gift of a literal and figurative pen, still as acerbic, still as charming, and still as sublime, from many years ago.

[Buy Niyi Osundare: A Literary Biography written by Sule E. Egya HERE.]

**************

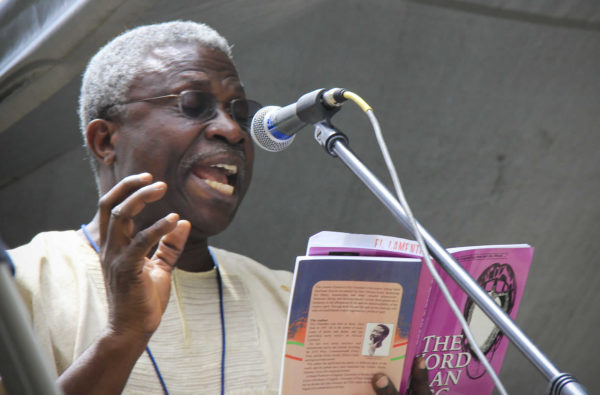

Post image via suedie.wordpress.com

****************

About the Author:

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s work has appeared in Aké Review, Brittle Paper, International Literary Quarterly, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, and recently in Literary Wonderlands, an anthology edited by Laura Miller. He is the winner of the Premio Ostana “Special Prize” 2016 (awarded in Ostana, Cuneo, Italy) for his work in indigenous language advocacy.

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s work has appeared in Aké Review, Brittle Paper, International Literary Quarterly, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, and recently in Literary Wonderlands, an anthology edited by Laura Miller. He is the winner of the Premio Ostana “Special Prize” 2016 (awarded in Ostana, Cuneo, Italy) for his work in indigenous language advocacy.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions