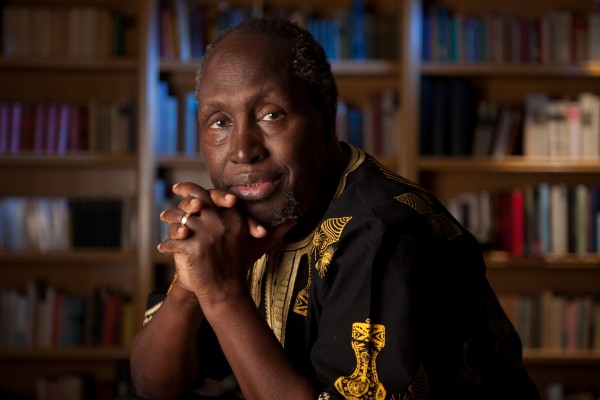

In a review for The New York Times, of the American Harvard professor Maya Jasanoff’s new book The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Global World, which considers the life and legacy of the Polish novelist, revered author Ngugi wa Thiong’o has revived the Chinua Achebe versus Joseph Conrad conversation, disagreeing with part of Achebe’s reading of him, pointing out similarities between the two men, and going as far as to call Conrad “a literary brother to Achebe.”

In 1975, Achebe gave a seminal lecture, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” in which he described Conrad, hitherto considered untouchable in the Western canon, as “a bloody racist.” Achebe’s reading has since defined studies of Conrad. While Ngugi agrees with “everything Achebe said about Conrad’s biases,” he “could not wholly embrace Achebe’s overwhelmingly negative view of ‘Heart of Darkness’ or Conrad in general.”

Describing The Dawn Watch as “fascinating” and as a “masterful study,” Ngugi zeroes in on both “the majesty and musicality of his [Conrad’s] well-structured sentences [that] had so thrilled me as a young writer” and—as something Achebe missed—“Conrad’s ability to capture the hypocrisy of the ‘civilizing mission’ and the material interests that drove capitalist empires, crushing the human spirit.”

The review is titled “The Contradictions of Joseph Conrad.” Here is an excerpt.

*

In the same way, Conrad and Chinua Achebe are also connected. And yet, Achebe led the charge against Conrad. In 1975 the Nigerian novelist delivered a lecture, “An Image of Africa: Racism in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” which was then published as an essay. He built on the insights of the groundbreaking literary critic Es’kia Mphahlele, who accused Europeans like Conrad of depicting Africans as acted on by history instead of making it. Achebe went ever further, calling Conrad a “bloody racist.” This critical perspective has become an inevitable companion to any discussion of the writer’s work. Jasanoff herself uses it to frame her quest for a more complex vision of Conrad.

Achebe’s essay helped explain what I had found repellent in Conrad’s work and why I’d stopped reading him. In the novels set in the outer reaches of European empire the native characters always seemed to merge with their environment, reminiscent of the Hegelian image of Africa as a land of childhood still enveloped in the dark mantle of the night. I accepted everything Achebe said about Conrad’s biases.

And yet, I could not wholly embrace Achebe’s overwhelmingly negative view of “Heart of Darkness” or Conrad in general. Somehow, the essay failed to explain what had once attracted me: Conrad’s ability to capture the hypocrisy of the “civilizing mission” and the material interests that drove capitalist empires, crushing the human spirit. Jasanoff does not forgive Conrad his blindness, but she does try to present his perspective on the changing, troubled world he traveled, a perspective that still has strong resonance today.

In “Heart of Darkness,” Conrad’s literary stand-in Charles Marlow talks of imperialism as a form of robbery accompanied by violence and aggravated murder on a grand scale. Colonial ventures are mostly about taking the earth away “from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves.” This captures, in one sentence, capitalism’s racist roots in slavery and conquest. Conrad also anticipated a capitalist system’s capacity to dismantle societies, a point he illustrated through his depiction of Mr. Holroyd, the cynical American silver and steel tycoon in “Nostromo.” Jasanoff does an excellent job pulling on all these threads.

I suspect Achebe missed this side of Conrad because he didn’t stop to consider the diabolical character of Kurtz, the brilliant station agent gone rogue whom it is Marlow’s task to retrieve. In “Heart of Darkness,” the final image of Kurtz, the man of light and reason, is one of him hedged by human heads, capturing the horror of imperialism and the hollowness of the enlightenment philosophy with which colonialism wrapped itself. It is a scene reminiscent of Marx’s comparison of bourgeois progress to the pagan idol who drank nectar but only from the skulls of the slain. Congo was littered with 10 million skulls, the work of civilized hunters for rubber and ivory to meet the greed of King Leopold of Belgium.

The Conrad who was able to imagine Kurtz in this way is often obscured by Marlow, Conrad’s literary alter ego. In “The Dawn Watch,” Jasanoff goes behind the mask and, like Stanley in search of Livingstone, or Marlow in search of Kurtz, sets out to find the elusive Conrad by tracing the physical, historical, biographical and literary footsteps of the writer. Born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski in 1857, in a Poland then under the thumb of czarist Russia and to parents engrossed in the struggle for independence, he later becomes a homeless traveler of the oceans, and eventually ended up as Joseph Conrad, an English-speaking citizen of the most global of the European capitalist empires of the time. Jasanoff returns Conrad to all of these contexts, understanding what impact they had on his novels.

In the process, she becomes a detective piecing together the incidents big and small that formed classics like “Lord Jim,” “Heart of Darkness,” “Under Western Eyes” and “Nostromo.” She helps us make sense of the seeming contradictory decision on Conrad’s part to write about the effect of empire but never set his novels in any of the colonial possessions of his adopted homeland, Britain, letting their actions unfold in mostly Dutch, Belgian and Spanish colonies.

And yet he remains one of us, a literary brother to Achebe. As Jasanoff reminds us, Conrad and his family were victims of the Russian Empire. Achebe and his people were victims of a Western empire. Both writers embraced English.

Read the full essay HERE.

Nsah Mala December 01, 2017 14:34

I am so glad to have been featured in this anthology, together with my mentor, Synthia Achoh. Thanks so much for selecting our work, Nonso. Thanks for publishing it, Brittle.