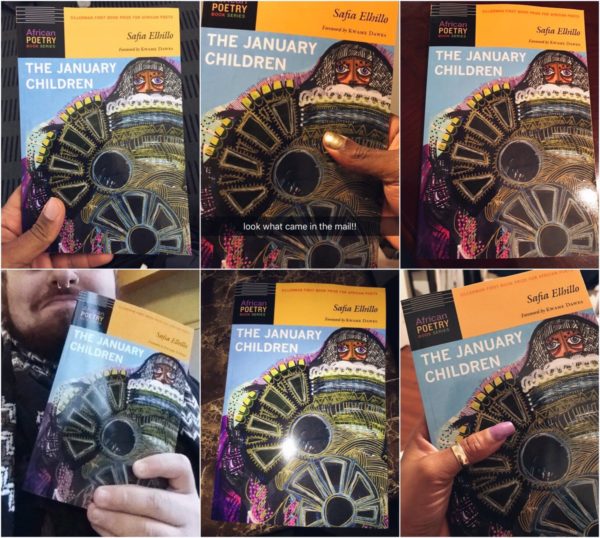

Sudanese poet Safia Elhillo has received the 2015 Brunel International African Poetry Prize, with her poem “application for assylum” shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Poetry. Her debut collection, The January Children, won the 2016 Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets, and was published in 2017 by the University of Nebraska Press. The term “January Children” refers to people born in Sudan under British colonial occupation, her grandfather’s generation; and in addition to their lives, Elhillo’s book explores familial and national history and what it means to be bilingual.

In a recent interview with Brooklyn Rail, she discusses her use of the late Egyptian music icon Abdel Halim Hafez as “a lens through which to interrogate many of these questions.”

Read an excerpt of the interview below:

Alex Dueben (Rail): Could you explain the title, because I don’t think this is well-known?

Safia Elhillo: The January Children are the generation born in Sudan under occupation. I also recently learned that this isn’t a phenomenon that’s unique to Sudan. Basically, children were lined up and assigned birth years by height and all given the birthdate January 1st. My maternal grandfather is of that generation.

Rail: The spine of the book is these poems about Abdel Halim Hafez. How did those poems start?

Elhillo: The process of writing these poems and this book was the opposite of what my process is usually like, where I’ll usually be like elbow-deep in something before I realize that I’m working on a project. With this, I decided that I wanted to write a book about Abdel Halim Hafez, but I did not know what that was going to look like, or even why. I tend towards obsession. I’d written a poem about Abdel Halim for a class assignment in my MFA program, and by that point I was feeling very overwhelmed by the whiteness of the program, so I started bringing in these Abdel Halim poems. It got to a point that I was not writing poems about anything else, for maybe a year. It wasn’t until I made up my mind that this is what I wanted to write a book about that I had to sit down and brainstorm what the points of connections between Abdel Halim and me were, and try and mine my obsession to figure out what its roots were.

A lot of the earlier poems were dealing with a caricature of him, which was all I knew. He was hugely famous, and there was no way I could have grown up in the household I grew up in and not known who he was. But all I knew about him was that he was very famous and very hot and sang love songs and that everybody was in love with him. He had a very hard and very sad life, and he died very young. The more I learned about him, though, the more he filled in as this human figure, and I think he became a more solid surface that I could experiment on. Once I was secure in my knowledge of Abdel Halim—and my relationship with Abdel Halim—I could trust him to be the subject and object of poems that were a little bit weirder and more conceptual.

Rail: Those poems end up being very personal and about your history and cultural background, and he becomes the lens you use to talk about these things.

Elhillo: It got to the point where I couldn’t be talking about Abdel Halim and talking about Egypt and talking about the Arab world without talking about race. That was, I think, a train of thought that I wasn’t expecting, but it became a matter of considering my own body as it relates to Abdel Halim’s body and the bodies that he sang to. He would address a lot of his love songs to “asmarani,” which is a term of endearment in Arabic for a brown-skinned or dark-skinned person. The term asmarani comes up in his songs so often, it’s almost as if she’s a recurring character, even though she’s not named.

And there are a lot of different interpretations [of the word]—some people think it means “swarthy,” some people think it means “brunette”, but my understanding of the word, and the way the word has been deployed in my life, is that it means dark-skinned. That felt pretty radical to me—that his song lyrics were taking time out to specify she was a darker girl. In this world that’s pretty racist and colorist, that felt important to me. There was also a big interview component to my research; I was just trying to talk to people from various generations about their relationship to Abdel Halim Hafez’s music—my grandma remembers where she was and what she was doing when he died. I think it hadn’t occurred to a lot of people, the significance of asmarani. I can’t remember who it was, but someone said that asmarani “doesn’t mean black so don’t think that.” That shook me, but also was very interesting—in the way that all painful things are kind of interesting. It opened up a whole other set of questions for me about this figure that I’d married myself to in this project.

Rail: I know in Arabic poetics the term habibi, which means beloved, is the typical object of affection. Is asmarani rare?

Elhillo: Not really. There’s a subgenre of mostly Egyptian songs I’ve encoun- tered. Asmarani is sort of a canonical love song figure at this point, but I don’t know how common or popular that was pre-Abdel Halim. All the other songs that I’ve encountered that use asmarani are more contemporary.

Rail: The opening poem of the book starts “verily everything that is lost will be / given a name & will not come back / but will live forever.” That feels like a mission statement in a way. Naming is important for you.

Elhillo: I think taking on asmarani as the character name was also a way to make all this personal. Part of the initial thought was to write about—and as—Abdel Halim’s asmarani, hence all the poems where I pretend to be his girlfriend. Asmarani was this figure that was sung about but never talked about, which was shocking to me. Also, in the way that most love songs are abstracted so that it can be about anyone, there was never any concrete asmarani that people could point to that Abdel Halim was singing to. He seems to have a very tragic and fraught love life. I think he never married. As a result of that, he was, like, the national boyfriend, where everyone could plug themselves into the song, and he would be singing about them. I don’t know if the number has been officially documented, but it’s said that at least fourteen Egyptian women killed themselves on the day of his funeral because they were just so distraught. The book is my turn to imagine myself as his asmarani. One more imagining in a long lineage of pretending to be his girlfriend.

Rail: I was struck throughout the book by how you talk about language. There is a sense of disconnection and exile, but something more, a disconnection from your own voice, in a way.

Elhillo: I think a not-uncommon symptom of being a child of diaspora is the privilege and torture of bilingualism. I have access to the two worlds that the two different languages contain, but I’m also never going to be entirely fluent in either because part of me will always belong to the other one. It’s been the source of a lot of shame, feeling not fully of one of those worlds or the other. A new development in trying to exorcise some of that shame is accepting that there’s a third language that forms in the hybrid space between the two of them, and that language is my first language, my native language. What I was trying to do in these poems that have both English and Arabic text in them was just trying to render, as directly as possible, the way that language actually works in my head, or in situations where I’m most comfortable. My mother and I, or my brother and I, or my cousins and I, we speak in this combination of Arabic and English. Those are the only situations where I don’t feel like I’m translating one to another because the word comes out in whatever language it was thought in. A lot of these poems, at their conception, were trying to cut out this process of translation that I have to do all day, every day. I wasn’t trying to write in anyone’s language but my own. Or in any language but the one that I feel most comfortable in. Then there’s an added step because the Arabic that’s in the book, for the most part, is pretty formal Arabic, whereas the Arabic that I speak at home—all Arabic is regionalized, every country has its dialect; so, I speak Sudanese Arabic at home. But I never really learned to render Sudanese Arabic in writing. The extent of my Arabic education was in Modern Standard Arabic, which no one speaks. It’s like Shakespearean English in that people will understand what you’re saying, but you’ll kind of sound like an asshole because it’s not a way that anyone conversationally speaks.

Read the full interview on Brooklyn Rail.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions