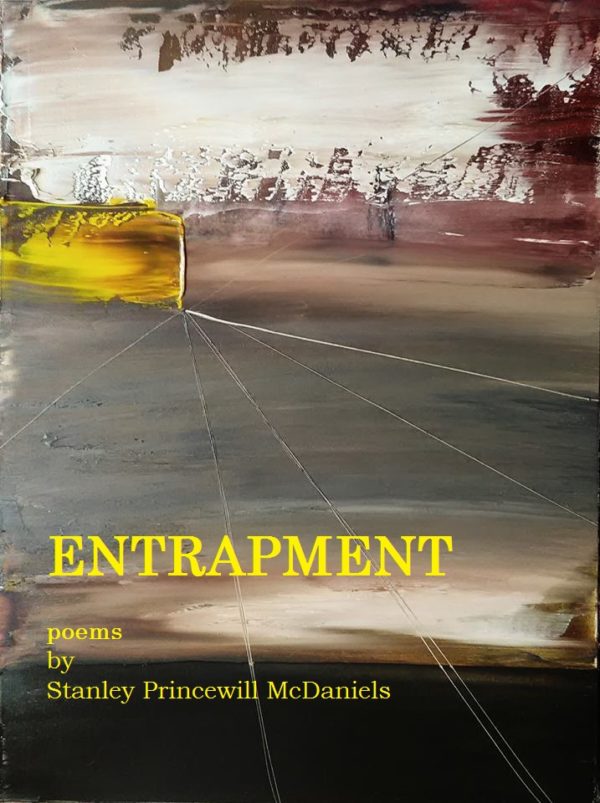

The Praxis Poetry Chapbook Series, an initiative of Praxis Magazine, publishes poetry chapbooks by new poets. It launched in 2016 with two remarkable e-books: Burnt Men, by Romeo Oriogun who went on to win the 2017 Brunel International African Poetry Prize, and The Ikemefuna Tributaries, by J.K. Anowe who went on to receive the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Poetry. Stanley Princewill McDaniels’ Entrapment was published in July 2017, with a foreword by Brittle Paper deputy editor Otosirieze Obi-Young and cover art by Robert Rhodes.

Read the foreword below.

*

In its preoccupation with the very personal—internal void, wanderlust, suicidal tendencies, masturbation, love, sex—the poems here find McDaniels in a tradition of emerging young Nigerian poets digging into the Self, into something very similar to, but more visceral than, Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s idea of “the geography of hunger.” This tradition, remarkable in its introspection and deliberate in its decentralisation of the societal, is best represented by two poets whose chapbooks were, coincidentally, published in this series last year: Romeo Oriogun, in the way the political is bent to his personal; and J.K. Anowe, who, by pegging his work in the psyche, is this tradition’s finest exponent, and the one with whom McDaniels shares kinship.

The poems here probe two major paths: self-search and self-pleasure. In the opener, “Persecution,” there is a search for freedom, a need for reassurance in existence, and in this search, as though functional, the persona is also a wanderer, propelled by wanderlust. “Everybody thinks I’m a false god,” he ruminates, his belief seemingly anchored in an alternate conviction. Then he stands in front of an oncoming vehicle and the poem ends, and we are left to infer whether or not he dies. This chain of void birthing lack of conviction birthing questions birthing resignation runs through the chapbook and, in a world he cannot relate to except through himself, keeps the persona trapped.

DOWNLOAD: Stanley Princewill McDaniels’ Entrapment

In “The Bottom Line of Loss,” he reflects: “Sometimes, to move on is to give up.” In “In a Blue Room with Two Inverted Chairs,” a voice that might be his as easily as it could be the author’s narrates the suicide of “a boy/ walking to the edge of a bridge/ He is the relic of a country/ wrecked by war.” In “Paranoia,” in which “A river runs behind the building/ on top of which a boy is preparing to jump off” and “Anne locked herself in her garage with/ her car running & lit a cigarette in hand,” the persona envies others not merely the freedom of death but the ability to decide to take their lives. In “Black Birds and Grey (Poem XLVI),” in which he is again possessed by wanderlust, he murmurs: “I take a seat at the end of silence/ & wait/ for my therapist again.” In “Crash Site (Poem LVI),” he coos it again, but this time as a foundational question: “Have you ever seen silence/ Have you seen me?” In likening himself to silence, we are allowed into his resignation; we realize that he has been saying a lot less than he feels. All through the collection, the persona’s reflections, wrought as they are in silence, are attempts to inhabit a similar process to what Gaamangwe Joy Mogami describes as “unbecoming invisible.”

But it is in the erotic that McDaniels’ art finds life, and in its detailed privacy of self-pleasure, we are enjoined to witness a persona propelled by a psychosexual drive, whose sole reprieves come in these brief moments. In “Testosterone,” his masturbation births “spasms of salty rain,” after we are treated to a metaphor in which his taking of his semen in his palms simulates a mother lifting her baby. To label this metaphor oedipal would be to over-analyze, because the persona’s phallic fixation might simply be what it is: an outlet. “Baby Rocker” is a coital movement in which his beloved is expected to feel in sex a stimulus for love. In “Transfiguration,” we watch him in post-coital bliss. But in “The Principle of Dying,” this finding of life is replaced with the French orgasm-as-death metaphor. Despite these, the persona here is not one for whom things can be made simple: he has difficulty accepting self-pleasure as total liberation: he likens it to sin. In “To a Lone Masturbator,” we see this: “Your mouth opens/ like the legs of a brief rain &/ something comes out like sin.”

Yet not all the poems here strictly follow this dual paradigm; the rest squirm in heartbreak, an in-between place. In “Appointment with the Black Birds,” there is physical distance between the persona and his love interest, and the result is strong: “Once I was darkness/ & the wound in my chest/ was hell.” In “For People with Problems about How to Love,” his need is more forceful than love; the poem captures that rare emotional intensity that, for some people, precedes love; that might even propel one into things love would not.

Throughout this chapbook, the Self is the canvas upon which is mapped turbulence, multi-level tension: between internal void and questions, life and death, pleasure and pain. This is captured, in “Buried” and “Black Birds and Grey (Poem XLVI),” with rousing references to a “sky at war.” Every emotion exuded by this persona is not grown to find a home in the world but to recollect in his mind and body. When it isn’t quite resignation that he feels, it is an awareness of the end. In this collection, there are places full of meanings, in both the body and the mind, that McDaniels opens.

Otosirieze Obi-Young,

July 2017.

DOWNLOAD: Stanley Princewill McDaniels’ Entrapment

Midlife Crisis Of A Major God II - Radr Africa March 05, 2019 16:23

[…] Brittle Paper, Tuck Magazine, Praxis Magazine, Bakwa Magazine, & elsewhere. His poetry chapbook Entrapment is available for download on […]