It isn’t that time of the year when we look back on what happened in it—that time is December, and this is February. But a delay in releasing this list seemed inevitable for a year that, on several levels, saw our literary culture expand. Organisations took groundbreaking steps: in March, Jalada Africa held a 12-city, 5-country mobile literary and arts festival in East and Central Africa; in April, the African Speculative Fiction Society (ASFS) announced the Nommo Awards, the first for speculative fiction on the continent, which was awarded in November; and in August, we announced the inaugural Brittle Paper Literary Awards, for fiction, poetry, nonfiction, and essays, which was awarded in October. Furthermore, two major magazines rose to prominence: South Africa-based The Johannesburg Review of Books and its well curated issues, and Botswana-based Africa in Dialogue which, with its conversations, has quickly become a library of profundity. Our delay stems partly from our need to rightly reflect all these in the list.

Read: The Brittle Paper Digest: 31 Notable Pieces of 2016

In 2016, our year-end list contained 31 pieces. For 2017, we round off at 79. We wanted a list that told a story of African Literature in 2017, that collects both its notable and its finest. Which brings us to this question: What counts as “notable”? The subject? The context? The writer? The writing? In our consideration, we looked, firstly, at the writing. And, secondly, at the writing. And, finally, at the subject and the context. We did not consider pieces that do not engage directly and primarily with our literary culture, that are not channeled into asking or answering questions about the conversations we are currently having. This means that such notable works as Petina Gappah’s “How Zimbabwe Freed Itself of Robert Mugabe” and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Rereading Albert Speer’s Inside the Third Reich,” both in The New Yorker and about politics, and Teju Cole’s photography essay, “Still Lives That Won’t Hold Still,” the longest sentence ever run by The New York Times, and Zinzi Clemmons’ call to boycott hipster racism, and Adichie’s fashion essay, “My Fashion Nationalism,” in Financial Times, and Diriye Osman’s pop culture pieces, all miss out. But this doesn’t mean that there aren’t works exploring politics or photography included here.

Books were not considered for this list. Only pieces published, or made available online, in 2017 were considered. But there are a few exceptions, for pieces published before 2017 but which came into focus during the year. Also not considered are pieces that aren’t accessible for free online, given that our hope with this is to create conversations about the state of our literary culture: What is happening? How can we engage with what is happening?

In this list is fiction that defines the talent on the scene, some of them rendered in brilliant prose. There is poetry that searches for humanity, that finds us in our hiding places, enough to lay a foundation for an emerging tradition. There is creative nonfiction that offers confession on our doorsteps, that steady our empathy. And here also—something we are particularly proud of—are culture-shifting think pieces and conversations, some of which happened on social media—Facebook, Twitter. The list is divided into five categories: Essays, Think Pieces, Letters, and Reviews; Poetry; Creative Nonfiction and Memoir; Fiction; and Conversations and Profiles.

From the editors of Brittle Paper, an invitation to these ideas in dialogue:

Essays, Think Pieces, Letters, and Reviews

“Verse Africa: The Malleable Poetics of Some Contemporary African Poets,” by Matthew Shenoda (Egypt), in World Literature Today:

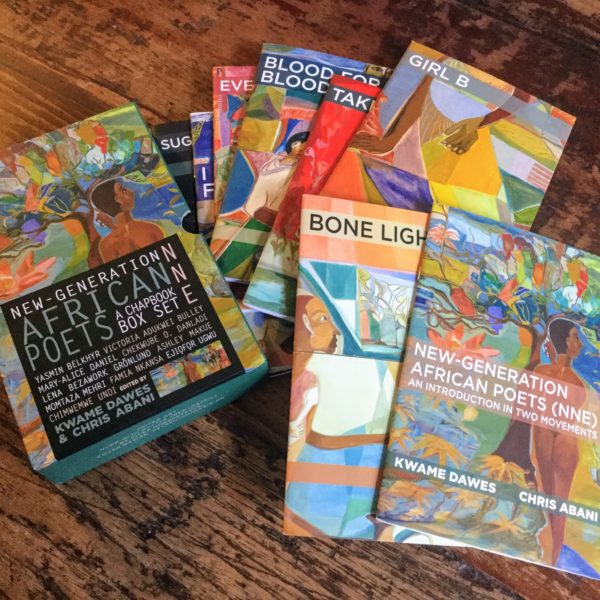

An engagement with poetry by select women from the continent: from the breadth in the iconic Ama Ata Aidoo and the Helen Yitah-edited collection of her work, After the Ceremonies: New and Selected Poems (2017), to the searching power in the Liberian Patricia Jabbeh Wesley and her When the Wanderers Come Home (2017), to the nuanced humanity in the Eritrean-Puerto Rican-African American Aracelis Girmay and her The Black Maria (2016), and centrally, to younger poets who came through the African Poetry Book Fund (APBF): the vision in the Somali Ladan Osman’s The Kitchen-Dweller’s Testimony (2015), the linguistic force of the Sudanese Safia Elhillo’s The January Children (2017), and the conceptual in Mahtem Shiferraw’s Fuchsia(2016). Mention is made also of Botswana’s TJ Dema, Ethiopia’s Liyou Libsekal, Somalia’s Warsan Shire, Zimbabwe’s Tsitsi Jaji, Kenya’s Ngwatilo Mawiyoo, Morocco’s Yasmin Belkhyr, Ghana’s Victoria Adukwei Bulley, and South Africa’s Ashley Makue.

“Penpoints, Gunpoints, and Dreams: A History of Creative Writing Instruction in East Africa,” by Billy Kahora (Kenya), in Chimurenga:

From Kampala to Ibadan to Nairobi, an important analysis of Ngugi’s beginnings and circumstances as a writer and the academia-driven development of the pioneering writers of modern African literature—Clark, Okigbo, Mphahlele, p’Bitek, Taban—down to the present-day attitude of writers to creative writing instructions. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Essays/Think Pieces.

“In the Shadow of Context,” by Kola Tubosun (Nigeria), in Enkare Review:

Citing Ivor A. Richards’ 1920s experiment, in which he tried to prevent a work’s context from influencing judgement of its quality, this essay probes, with examples from all over the world of how authors’ names aid or limit their chances, whether the judging of literary prizes in Africa is being dictated not by the excellence of the works in contention but by the names of their authors. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Essays/Think Pieces.

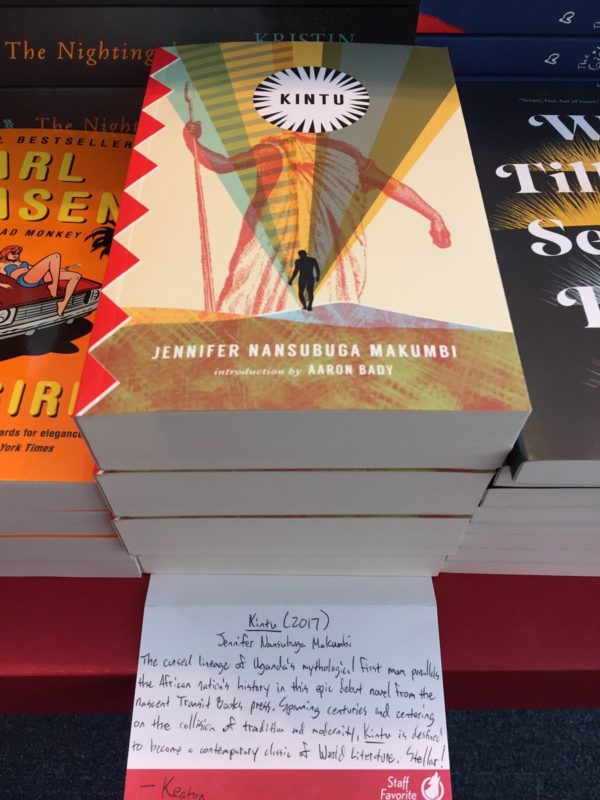

“In Kintu, a Look at What It Means to Be Ugandan Now,” by Aaron Bady (U.S.A.), in Literary Hub:

The introduction to the U.S. edition of Jennifer Makumbi’s Kintu (first published in 2014), a reimagination of Ugandan history through the bloodline of the Kintu clan, is an appraisal of the novel’s immediate and projected impact as well as its success in providing a corrective narrative of Ugandan history. Hailing it as the Great Ugandan Novel, it offers an important personal background to the work and situates its relationship to Things Fall Apart. But the authorship of the introduction—a white man explaining the work of a black African woman—proved divisive.

“When We Talk about Kintu,” by Ellah Wakatama Allfrey (Zimbabwe/ UK), in Brittle Paper:

A gentle but firm protest, in our era of mansplaining, against the tendency in Western publishing to not let literature from black Africa speak for itself, following the inclusion of an introduction—by a white male—in the 2017 US edition of Jennifer Makumbi’s 2014 debut novel Kintu, and the billing accorded his name on the book’s cover. An important call for the need for homegrown promotion networks. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Essays/Think Pieces.

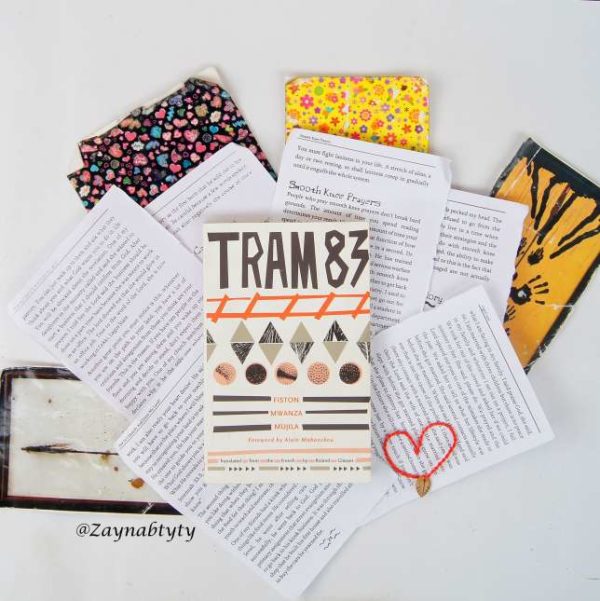

“Mujila Fiston Mwanza’s Tram 83: Requiem for the African Writer, and Again, the Balance of Today’s Stories,” by Ikhide R. Ikheloa (Nigeria), in Xokigbo:

In April, a single essay about a hitherto spotlessly appraised novel set a continent on fire. The assertions about Tram 83’s style, structure and perceived politics—that the novel is poverty porn and plays to stereotypes about Africa; that it is misogynist; that it reads like a failed movie script; that the book simply does not deserve the praise accorded it, including its win of the 2015 Etisalat Prize—are perhaps unprecedented for a book with such visibility. Which is why the response to it, intense and divisive, gave us a truly continental conversation that might itself be unprecedented, and that, importantly, shifted the expectations of what representative writing is—if there is such a thing as that.

“Poverty Porn: A New Prison for African Writers,” by Richard Oduor Oduku (Kenya), in Richardoduor.wordpress.com:

A solid, brainy outgrowth of the heated conversation around Fiston Mujila’s Tram 83, this essay decries the deficiencies of anthropological reading in an era of genre-bending literature, cautioning against analysing works based on specific political views. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Essays/Think Pieces.

“An Architect of Dreams: On Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Devil on the Cross,” by Tope Folarin (Nigeria), in Los Angeles Review of Books:

Linking everything from Venus Williams and racism to matatu and barbershops and Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Devil on the Cross, this essay is case for the power of dreams and their ability to forge their own reality in the face of strong discouragement, and an analysis of the connection between Africa’s present reality and the dreams of conquest had by European imperialists. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Essays/Think Pieces.

“Translating Guinea-Bissau’s First English-Language Novel,” by Jethro Soutar (UK), in Brittle Paper:

Following the publication of Abdulai Sila’s Lusophone-language novel A Última Tragédia in English as The Ultimate Tragedy, its translator offers a unique take on the rigours of translating, in a way that captures contemporariness.

“Writes of Passage, an Urban Memoir,” by Bongani Madondo (South Africa), in The Johannesburg Review of Books:

An excitingly steeped tribute, supplemented by film, music and urban references, to the culturing power of Transition, Rolling Stone and Vibe magazines on the intellectual culture of specific periods. A personal history of literary and political eclecticism and diversity. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Essays/Think Pieces.

“The Labours of the Months: Of Work and Its Refuseniks,” by Rotimi Babatunde (Nigeria), in Praxis:

A work of intense intellectualism that traces the exploration of work in literature, and the intersection of both with play, from the medieval to the modern period, situating Amos Tutuola, Chinua Achebe, Hesiod, Aristotle, Dante, Charles Dickens, Ivan Goncharov, George Orwell, Joseph Brodsky and the illuminated manuscript gallery Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry in a robust, often-overlooked tradition. It serves as the introduction to the second Art Naija anthology, Work Naija: The Book of Vocations. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Essays/Think Pieces.

“All Your Faves Are Problematic: A Brief History of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Stanning, and #BlackGirlMagic,” by Sisonke Msimang (South Africa), in Africa Is a Country:

An illuminating dissection of black female celebrity in the era of #BlackGirlMagic, this essay weighs Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s celebrity—following her criticized comments on the place of trans women in feminism—against a culture that does not hesitate to attack its favourites, capturing insights on the workings of modern pop culture conversations. It won the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Essays/Think Pieces.

“Strange Things in the Stream of Warm, Dark Life,” by John “Lighthouse” Oyewale (Nigeria), in The Kalahari Review:

Analytical writing meets memoir in this tribute to the late Peter Abraham’s Mine Boy (1946) which highlights its treatment of race in Apartheid South Africa, as well as focuses on its characters while sifting through Abrahams’ biography for likely inspirations for elements in the work.

“The Contradictions of Joseph Conrad,” by Ngugi wa Thiong’o (Kenya), in The New York Times:

In this review of the American Harvard professor Maya Jasanoff’s The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Global World, Ngugi revives the Chinua Achebe versus Joseph Conrad conversation, disagreeing with part of Achebe’s reading of him—particularly his overlooking of Conrad’s capture of the hypocrisy and materialism of colonialism—pointing out similarities between the two men, and going as far as to call Conrad “a literary brother to Achebe.”

“Dear Tete Petina: I Am Not on the Caine Prize Shortlist,” by Petina Gappah (Zimbabwe), in Brittle Paper:

An agony aunt-style letter to a writer saddened by their non-inclusion in the 2017 Caine Prize shortlist sees one of the continent’s central writers reveal her own career progress and relationship with literary prizes. One of our most-read pieces of 2017.

“Me and My Afro,” by Imbolo Mbue (Cameroun), in The Guardian:

Through both metaphor and direct juxtaposition, this essay about personal struggles with afro hair doubles as a reflection on the language-hinged political struggle in Cameroun, allowing for an emotionally charged read that reminds us of the potency in the combination of the personal, the artistic and the political.

“Juliane Okot Bitek’s 100 Days Is a Masterpiece” by Diriye Osman (Somalia), in Huffington Post:

A brief ode to Ugandan poet Juliane Okot Bitek’s poetry collection in memory of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide.

“Does Stay with Me Stay with You?” by Kayode Faniyi (Nigeria), in Brittle Paper:

An analysis of Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay with Me (2016) and Chigozie Obioma’s The Fishermen (2015)—both seen as Yoruba-novels-in-English—that dwells as much on lingual-cultural verisimilitude as on characterisation, setting, politics, and interestingly—as if to highlight yet another conversation we aren’t quite having—prose styles. Partly an effort to situate both books within the literary tradition.

“African Science Fiction,” by Mark Bould (UK), in Los Angeles Review of Books:

This review of the Moradewun Adejunmobi-edited Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry’s Volume 3, Issue 3 (2016) is a competent overview of science fiction in not only literature by Africans but also in filmmaking. The issue is compared to Paradoxa’s “Africa SF” (2014), and is then fleshed out: Magali Armillas-Tiseyra’s work on Sony Labou Tansi’s Life and a Half (1979), Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Wizard of the Crow (2006), Deji Bryce Olukotun’s Nigerians in Space (2014), Cristina de Middel’s photographic collection The Afronauts (2012), and Frances Bodomo’s short film Afronauts (2014); Hugh O’Connell’s on Nnedi Okorafor’s Lagoon (2014); Ian P. MacDonald’s on Kojo Laing’s Big Bishop Roko and the Altar Gangsters (2006); Nedine Moonsamy’s on the groundbreaking, Ivor Hartmann-edited AfroSF: Science Fiction by African Writers (2012); and Brady Smith’s on Lauren Beukes’s Moxyland (2008) and Zoo City (2010). It is essays like this that clear critical paths for whole genres of art.

“Memo to Poets,” by Kwame Dawes (Ghana), on Twitter:

Writing tips for poets dished out on twitter by the most accomplished poet from the continent: the do’s and don’t’s of writing poetry, and, to an extent, writing in general. They include things to be wary of, one or two warnings, as well as suggested moderation on the use of similes and metaphors.

“Why I No Longer Use the Term ‘Game’ for Bushmeat,” by Chika Unigwe (Nigeria), in Brittle Paper:

Once in a while comes an intervention that stirs up social media. This Facebook post is a thought-provoking reflection on the power in names. It uses the distinction between the standard English term for wild-caught meat, “game,” and the Nigerian term, “bushmeat,” to expose the dark underbelly of linguistic practices that we tend to take for granted. The short but hard-hitting statement is a call to us to be vigilant about how language can paradoxically be used to suppress our voices.

“Writing’s on the Wall for Parochial SA Publishers,” by Zukiswa Wanner (South Africa), in Guardian and Mail:

A challenge of South Africa’s white-dominated “parochial publishing industry,” this piece zeroes in on prevailing one-sided narratives: that nonfiction sells more than fiction in the country, that black people don’t read. It highlights how the system is structured to not favour black booksellers. A call for inclusivity that cannot be overemphasized.

“We’re Queer, We’re Here,” by Chibuihe Obi (Nigeria), in Brittle Paper:

A personal history of the scarcity of queer voices in Nigerian literature and the physical suppression and violence meted out to queer Nigerians, coming at a time when Nigerian writers have come under persecution for writing about queerness. It won the 2017 Brittle Paper Anniversary Award.

“Selective Empathy: Stories and the Power of Narrative,” by Aminatta Forna (Sierra Leone/ Scotland), in World Literature Today:

A treatise on the indispensability of stories and storytellers, their ability to transport and portray, and the tendency of literary fiction to affect psychology and change readers’ behaviour. It draws from the childhood reading of one of our leading writers, relates the theories in the French pyschologist Boris Cyrulnik’s Resilience (2009) to storytelling itself, and refers to specific meaning derived from the craft by specific storytellers—Chinua Achebe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Mariama Bâ, Buchi Emecheta, Ama Ata Aidoo, Miriam Tlali, Viet Thanh Nguyen. Using the work of Binyavanga Wainaina, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Teju Cole, Dinaw Mengestu, Chris Abani, Okey Ndibe, and her own The Memory of Love and The Hired Man, it highlights how generations build on the work of their predecessors. It was nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

“On Alain Mabanckou,” Brittle Paper Editorial:

An in-depth exploration of the relevance and place of the Congolese novelist Alain Mabanckou, whose openness to the unconventional, partly as a result of inhabiting multiple locations of culture and working within different literary archives and traditions, gives his work an unruly, unboxable quality. Mabanckou’s search for new forms of storytelling has birthed the dark, digressive, humorous, unpunctuated-aside-commas Broken Glass (2005), and other experimental, fun works in African Psycho (2003), Memoirs of a Porcupine (2006), The Lights of Pointe-Noire (2013), which offer up killer openers. His drawing from, and bridging, the Francophone and Anglophone literary spheres is essentially what would happen if Amos Tutuola and Mongo Beti ended up in a bar trading stories while Achebe sat in the corner trying—lovingly—to temper their excesses.

“Speaking Shona Was Associated with Humiliation,” by Petina Gappah (Zimbabwe), in The Johannesburg Review of Books:

One of the five afterwords to the new German edition of Ngugi’s iconic collection of essays, Decolonising the Mind—the others are by South Africa’s Sonwabiso Ngcowa, Senegal’s Boubacar Boris Diop, Cameroon’s Achille Mbembe, and Kenya’s Mukoma wa Ngugi—this is a reflection of a an experience similar to that which led Ngugi to launch his language revolution. It uses Jean-Paul Sartre’s introduction to Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961) and Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions (1988) to highlight the lingual wound wrought by colonialism in education in Africa, while allowing a disagreement with Ngugi’s call to abandon European languages as it does not recognize the multiple ways in which Africans can be.

“Dear Mr. Brittle: Has Queer Literature Become a ‘Trend’ in Africa?” Brittle Paper Editorial:

An agony uncle-style letter addressed to a young writer so puzzled and skeptical of literature humanizing queerness that he attributes it to a “trend” and the politics of awards recognition. It traces literature so far written about queer Africans, both works that demonize and humanize queerness, from the 1960s to the present day, and lays out strong logic that shows how literature about queer Africans gained visibility both as a result of larger cultural and artistic forces and as a fidelity to the everyday realities of queer Africans, and with statistics to prove how African literature has consistently and loudly overlooked and boxed literature about queerness and its writers.

“The Colonizer’s Archive Is a Crooked Finger,” by Emmanuel Iduma (Nigeria), in Catapult:

In assuredly paced, transportive prose that offers a calming lesson in style, the life of a 1920s Nigerian schoolteacher is used to enter a world in which photography by colonialists assaulted the Nigerian body, in interpretations that seem to hold their subjects in question. An insight into how photographs name and define their subjects, especially when those people wouldn’t see themselves in said way, and sensitively, the ways in which the body demands and tries to set the terms of engagement.

“A Stranger in ‘the Village,’” by Bongani Madondo (South Africa), in The Johannesburg Review of Books:

Following the end of its print run, an eloquent reminisce—its title a pun on that of James Baldwin’s 1953 Harper’s essay—of the well-regarded American newspaper The Village Voice and its performatively Brechtian issues. We are taken into a story of culture-propelled intellectualism peaking with the magazine’s coverage of Michael Jackson’s demise. This writer is, in his own words, “a trafficker in word-magic.” And no one writes about magazines and the feel of print like he does, not in such prose of sensual delight as contained in its first section.

“My Mentor: Sarah Ladipo Manyika,” by Tendai Huchu (Zimbabwe), in Brittle Paper:

In what might as well be a letter to young writers, the author of The Hairdresser of Harare (2010) and The Maestro, The Magistrate & The Mathematician (2014) lets us in on his journey to teaching himself with the novels of Sarah Ladipo Manyika—In Dependence (2008) and Like a Mule Bring Ice Cream to the Sun (2016)—and with a personal touch.

“An African Exodus,” by Diana Evans (UK), in Financial Times:

A review of Chike Frankie Edozien’s susbstantial Lives of Great Men (2017), the first memoir by a Nigerian to focus on gay men. The book collects their stories, from Nigeria and Ghana to Uganda and Tanzania and Zimbabwe, these men who have had to leave their homelands due to state-backed homophobia.

“How Little Has Changed in Thirty-Nine Years,” by Efemia Chela (South Africa), in The Johannesburg Review of Books:

In the opening piece of her “Temporary Sojourner” series, a search for what the author calls “Zimbabwe’s own story of itself” leads to a reading of Dambudzo Marechera’s The House of Hunger (1978), reinstating the novella’s relevance in the present day.

“Dear Genevieve: Parts 1-10,” by Ikhide R. Ikheloa, in Brittle Paper:

A 10-part letter series addressed to a new writer trying to find their way in the literary ecosystem. The letters focus on everything from finding one’s voice and writing space to truthtelling and remuneration, from the need for innovation and funding to the need to read good writing.

“James Baldwin in Rhodesia,” by Percy Zvomuya (Zimbabwe), in The Johannesburg Review of Books:

Following a thread of intellectual relationships between African Americans and South Africans, an assessment of the influence exerted on James Baldwin by Michael Raeburn’s collection of stories Black Fire! Accounts of the Guerrilla War in Rhodesia (1978)—a book Baldwin blurbed, wrote its introduction, and later reviewed. An analysis of ideas—views on violence, racial tension—reflected in both the book and Baldwin’s work.

“Bessie Head’s Letters: The Pain, the Beauty, the Humor,” Brittle Paper Editorial:

A rumination on Bessie Head’s raw, honest, loud, humourous, and intellectually deep 1991 volume of essays, A Gesture of Belonging: Letters from Bessie Head, comprising letters shared with the book’s editor Randolph Vigne, her confidante. They span over a decade—from 1965, when Vigne lived in London, to 1979, when Head lived in Serowe, Botswana as a political refugee and a single mother—uncovering the traumas, insecurities, and the creative life of one of Africa’s most celebrated writers.

Poetry

“Your Body Is War,” by Mahtem Shifferaw (Ethiopia/ Eritrea), in Hermeneutic Chaos Journal:

A comparison of self-inflicted bodily harm to war that beautifully draws their manifestation in love and death. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Poetry.

“Credo to Leave,” by JK Anowe (Nigeria), in Expound:

Through lines of abrupt clarity, the voice’s no-fucks-given attitude and vulnerability in sexual pleasure draw upon deep existential pain, exposing a young suicidal mind teasing itself—or racing?—towards controlled implosion. An important entry point to an emerging sub-tradition of Nigerian poetry focused on depression. It won the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Poetry.

“A Series of Solitudes,” by Fiston Mwanza Mujila (DR Congo), in Enkare Review:

A resonant use of water and animal metaphors to explain a body in dishevelment, in graphic language that nods to musical references. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Poetry.

“Pythagoras Theorem,” by Nick Makoha (Uganda), in Adda:

This poem weighs communality and divisibility on mathematical terms—the Pythagoras theorem, algebra, denominators—with effective precision. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Poetry.

“6 Errant Thoughts on Being a Refugee,” by Sarah Lubala (South Africa/Congo), in Brittle Paper:

These short lines, as in her “Boy with the Flying Cheekbones” and “Portrait of a Girl at the Border Wall,” carry need and mourning and longing, its end like resignation.

“application for asylum,” by Safia Elhillo (Sudan), in Frontier Poetry:

A chilling relation of fear and loss to water laid out in intriguing questions and answers, its play with language an allure. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Poetry.

“I Ask My Brother Jonathan to Write about Oakland, and He Describes His Room,” by Yalie Kamara (Sierra Leone/ USA), in African Poetry Prize:

Channeling literature, polemic and painting, a poet writes around the racial realities of his city in a conscious effort to see to the preservation of his black body in a majority-white land: a clever work that speaks even louder now. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Poetry.

“Schoolyard Cannibal,” by Nana Nkweti (Cameroon), in Brittle Paper:

An engrossing parody of racist commentary and history, in schools and socialization circles, complete with animal references, depicting, even in its highlighting of glorious historical achievers, the far-reaching turmoil of a race. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Anniversary Award.

Creative Nonfiction and Memoir

“Out of Europe—Traveling with the Caine Prize in Germany,” by Rotimi Babatunde (Nigeria), in Caine Prize Blog:

Offered in the second-person, in sharp, observant prose, this essay’s command of history and choice of references elevate it from an insightful travel piece—from Turkey to Germany to attend workshops—to a searing revisitation of historical ironies. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Creative Nonfiction.

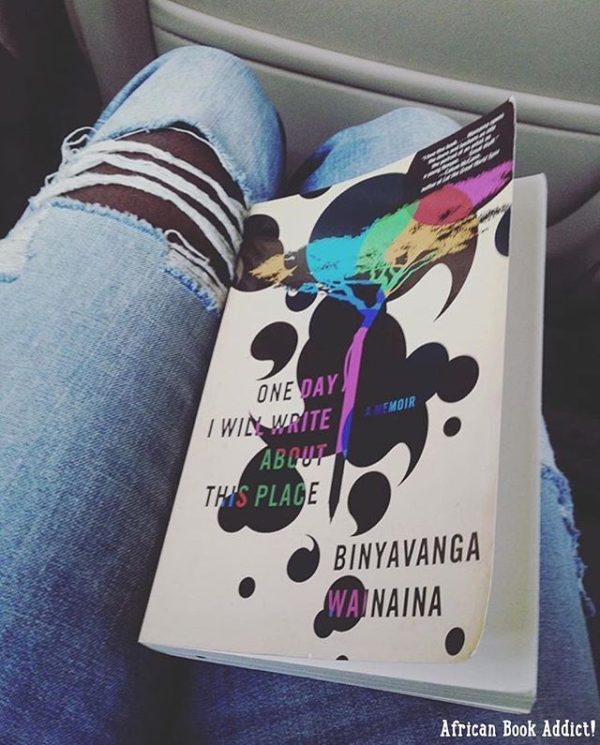

“Since Everything Was Suddening into a Hurricane,” by Binyavanga Wainaina (Kenya), in Granta:

With its unconventional use of punctuation and syntax and capitalisation and paragraphing, a groundbreaking work. Its fragmented, heartbroken prose pushes it teasingly close to poetry. Here, new words are created by mixing adjectives, blending nouns, transforming nouns into verbs, enough to generate a conversation on literary experimentation. A reminder of something often overlooked: that this is the finest prose-crafter of his generation. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Creative Nonfiction.

“How to Gossip About African Writing in Geneva,” by Oris Aigbokhaevbolo (Nigeria), in Catapult:

Opening with one of the finer paragraphs around, we are treated, in chatty, chewable prose, to a visit to Geneva, a rumination on cultural quirks, and centrally, a meeting with the novelist Petina Gappah—warm, witty, an object of admiration. We are let into more rumination, of the writer’s beginnings in the business, of bits of writing-career wisdom, of Gappah getting a guitar. An exploration of what it means to meet writers, especially when they are older and don’t want—or, in a cited case, want—to be written about.

“How It Ends,” by Troy Onyango (Kenya), in The Magunga:

Brief and contemplative, a behavioral study of assured beauty, of a young mind craving to recollect his place in his own world but riddled by doubt. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Creative Nonfiction.

“Naijographia,” by Bethuel Muthee (Kenya), in Enkare Review:

A psychogeographical reading of Nairobi that touches on science, political environmental policies, death, the human body, and the city’s history of patriarchal violence, in English and Swahili. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Creative Nonfiction.

“Soweto, Heart of a Nation,” by Niq Mhlongo (South Africa), in The Johannesburg Review of Books:

A sampling of places seeable in vibrant Soweto—the Diepkloof Extension, its “little mountain,” the Orlando Towers, Chiawelo, Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, the University of Johannesburg’s Soweto Campus, Pimville, the Hector Pieterson Memorial, Vilakazi Street, the Eyethu Lifestyle Centre, the E’Socialink, Bafokeng Corner, Kasi Beer Garden, Credo Mutwa Cultural Village—that captures the spirit of its people, while teasing a reflection on the inequalities of South Africa.

“Chapter Thirty-Three,” by Binyavanga Wainaina (Kenya), in Brittle Paper:

The last chapter, yet, from his acclaimed memoir, One Day I Will Write About This Place (2011)—the second chapter to arrive after the book—moves across decades, from 1983 to 1972 to 2010 to 1940, and across childhood cultural impressions and adulthood political moments in Kenya, from fascination with music and music instruments to indulgence in masturbation to recounts of Kenyatta and Moi, allowing a read as wholesome as anything.

Fiction

“Farang,” by Megan Ross (South Africa), in Short Story Day Africa: Migrations:

An aching romance, through intimacy and companionship and pregnancy, a reflection on love and language, foreknowledge and inevitability, set in Thailand and South Africa, in prose so lyrical and controlled it moves like a spring. It received the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Fiction and was a finalist for the 2016 Short Story Day Africa Prize.

“Triptych: Texas Pool Party,” by Namwali Serpell (Zambia), in Triple Canopy:

This fictionalized account of the 2015 McKinney, Texas pool party incident in which a police man tackles and restrains a 15-year-old black girl is a compendium of chatty, political lyricality, its use of animal and Greek-mythology metaphors a delight. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Fiction.

“Squad,” by Linda Musita (Kenya), in Enkare Review:

Written entirely in convincing dialogue, this conversation between two female acquaintances about their other female acquaintances whose behaviour towards other women are pretentious is an examination of clique angst that briefly uses as metaphor the Kenyan artist Boniface Maina’s abstract expressionist, surrealist paintings. In its aggressively feminist tone, we are offered killer-phrases for fake feminists: The Femioso, Cunt Psychosis. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Fiction.

“The Weight of Silence,” by Abubakar Adam Ibrahim (Nigeria), in Brittle Paper:

With slowly unraveling emotional power, this story written entirely in questions follows two friends—one the narrator, the other in coma—through a childhood of envious infatuation with a teacher they might have murdered, a memory of obsession and blame that torments them all through their lives. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Anniversary Award.

“The Story of the Girl Whose Birds Flew Away,” by Bushra al-Fadil (Sudan), Translated by Max Shmookler, in The Book of Khartoum: A City in Short Fiction:

This evocative, dislocated narration by an unnamed city-dweller too keen and curious for his own sanity offers stark poetry, of the narrator’s enchantment with the titular female. It is about isolation and excommunication, about cutting through the aesthetic chaos of existence, and possible redemption through infatuation. With its delicate musicality filled with alliteration, this is best appreciated as art for its own sake. First published 38 years ago in Sudanese, then translated into the English in 2012, this story is a bridge: it exposes the reader-in-English to the treasures of the indigenous Sudanese literary sphere. It won the 2017 Caine Prize.

“A Door Ajar,” by Sibongile Fisher (South Africa), in Short Story Day Africa: Migrations:

A product of a riotous imagination, of a family and community of females for whom life is a tough mix of violence, love, betrayal, tradition, and an insatiable thirst for home. With sentence after sentence of resonating portrayal, its matriarchal culture is as remarkable for its violent normality as it is for its beautiful placement of femaleness. A finalist for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Fiction and the 2016 Short Story Day Africa Prize.

“A Reversal,” by Imbolo Mbue (Cameroun), in Bakwa:

A midnight phone call between father and daughter reveals layers in the feeling that is belonging. Its brevity is compensated by the fullness that is its emotional acuity. The significance of its appearance in the Camerounian magazine Bakwa is not lost on observers.

“The Shoes,” by Edwige-Renee Dro (Cote d’Ivoire), in La Shamba:

The purchase of a pair of shoes, at the price of a 50kg bag of rice, leads to cracks in a family.

“By Way of a Life Plot,” by Kelechi Njoku (Nigeria), in Adda:

In following a suicide attempt gone wrong—or gone uncompleted—this story deploys sarcasm and humour to effect. The successful man at its center intends to take his life because he cannot possibly be more successful than he already is, and reading his efforts to ensure this feels both like humouring him and being humoured. It was shortlisted for the 2017 Commonwealth Short Story Prize for Africa Region.

“Ships in High Transit,” by Binyavanga Wainaina (Kenya), in Expound:

Plot and characterization take the back seat in this celebration of language in roaming prose. The rumination here moves from erotic intellectualism to cultural references to satisfaction in its own possibilities. Shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Fiction.

“The Virus,” by Magogodi Makhene (South Africa), in Harvard Review:

Wrought in high imagination and complexity, this heavily narrated story of South Africa’s historical scrambles and cyber-terrorism succeeds in twisting the political into the artistic. A veteran fights to keep Boer territories from enemies while worrying about the invasion, by Americans, of Africa, a continent which “having never really been inter-webbed, is the one true refuge.” A peer into a future, and possibilities, of cyber-terrorism. Shortlisted for the 2017 Caine Prize.

“Sahara,” by Shadreck Chikoti (Malawi), in All the Good Things Around Us: An Anthology of African Short Stories and Manchester Review:

After his 102-year-old psychiatrist assures him that “there is no such a thing as paranormal in the multiverse,” a journalist man meets a gynoid at a fuel pump and is subsequently led into a web of connections upon whom the survival of humanity depends.

“Tea,” by TJ Benson (Nigeria), in Short Story Day Africa: Migrations:

This tale of apprentice porn actors—a Tiv female and a German male—who murder their employers in Italy and, with only a rudimentary understanding of English, must find a way to communicate in order to avoid arrest is told with cinematic range. In plain prose that does not hide its movie influences, a multicultural mix in human-trafficking that becomes a critique of the human need for, and adaptation to, communication. A finalist for the 2016 Short Story Day Africa Prize and the 2017 Brittle Paper Award for Fiction.

Conversations and Profiles

“So Many Ways of Knowing”: An Interview with Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi (Uganda), in Los Angeles Review of Books

Makumbi’s opinions are worth pausing for: Feminism would remain incomplete without confronting the ways in which patriarchy cages men as well; what Idi Amin contributed to Islam; her experience with patronising publishers; Europe’s bringing of homophobia to Africa; and her decision to refer to Ugandans in the West as expatriates rather than immigrants, the way Westerners would refer to their people in Africa.

“The Nigerian-American Writer Who Takes on Taboos,” Profile of Chinelo Okparanta by Sarah Ladipo Manyika (Nigeria), in OZY:

A focus on the reception of her body of work which explores queerness: the story collection Happiness, Like Water (2013) and the novel Under the Udala Trees (2016), which is the first by a Nigerian to centralize lesbian characters. Both books received the LAMBDA Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction, and, as evident in her much-discussed panel at the 2016 Ake Festival, serve as an entry point to the conversations around queerness in Nigerian literature.

“Poetry and the Fullness of Things,” A Conversation by Ejiofor Ugwu (Nigeria) and Gaamangwe Joy Mogami (Botswana), in Africa in Dialogue:

A pondering, on loss and completeness, through the significance of things, in a world of violence and violations, and of the protests poetry registers against the human soul, the questions that poetry asks of God.

“Petina Gappah Speaks About the Highs and Lows of Her Writing Career, and Reveals Details of Her Next Book,” A Conversation with Bongani Kona (Zimbabwe), in The Johannesburg Review of Books

A discussion about black writers and sociopolitical pressure in Southern Africa, Gappah’s balancing of writing with her other profession as a lawyer, the progression of her career, her mastery of dialogue, Zimbabwean languages, politics and music, the humour in her writing, her approaches to writing short stories and her novel, and how her body of work captures “what it has meant to be Zimbabwean in recent times.”

“Un-Silencing Queer Nigeria,” Brittle Paper Anniversary Conversation with Romeo Oriogun, Arinze Ifeakandu, Kelechi Njoku, and Laura Ahmed, on Facebook:

This moment that redefined the visibility of Nigerian literature about queerness featured a handful of the country’s notable young writers unburdening their experiences, taking control of the narrative mostly skewed against queer Nigerians, creating an entirely new one. They discuss identity politics, the burden of the term “queer literature,” the impact of the queer art collective 14, the violence and hate campaign meted out to writers exploring queerness, the traditional silence of the literary community, the subtle attempts to censor writing about queerness, and the intersection of the movements for LGBTQI rights and gender equality. Nothing was spared. A highlight of the year.

“The Art of Unlearning,” A Conversation by Koleka Putuma (South Africa) and Gaamangwe Joy Mogami (Botswana), in Africa in Dialogue:

Through blackness and femaleness, through trauma and love, an exposition of why artists must learn to express trauma and pain, of their persons and of their cultures, unreservedly.

“Interview with 2017 Brunel International African Poetry Prize Shortlisted Poet, Romeo Oriogun,” A Conversation with Geosi Gyasi (Ghana), in Geosi Reads

The eventual winner of the Brunel Prize discusses his beginnings in poetry, the impact of J.P. Clark’s “Streamside Exchange” on him, a poem he wrote for a gay friend who “ran through the desert to Italy last year. . . before they lynched him,” his own experience with threats and abuse, and his poetry embedded in a vision of social change for queer people in Nigeria, a country where it is legal to hunt them.

“Is Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s Tram 83 Misogynist Poverty Porn? Parts One and Two,” A Conversation by Ikhide R. Ikheloa (Nigeria), Zukiswa Wanner (South Africa), Richard Oduor Oduku (Kenya), Bwesigwe Bwa Mwesigire (Uganda), Petina Gappah (Zimbabwe), Ainehi Edoro (Nigeria), Tsitsi Dangarembga (Zimbabwe) and Others, on Facebook:

A portrait of intellectual engagement, what began as an essay on a blog entered Facebook and ended as arguably the most continental literary conversation of the social media era in Africa, with nearly everybody having something to say about the award-winning, stylistically-remarkable novel Tram 83. Does the depiction of misogyny mean that the one who depicts it the way it is has become misogynist? Does capturing the reality of poverty on a continent translate to poverty porn because the continent has become synonymous with poverty in global narratives? If not, where then is the line between honest depiction and poverty porn? Where is the line of sensitivity when men write about women’s sexuality? Is it that, in the throes of a work’s excellent style, we often overlook the details and manner of a work’s substance? One of the responses would be shortlisted for the inaugural Brittle Paper Award for Essays.

“The Origin of Homophobia and Misogyny,” A Conversation by Gaamangwe Joy Mogami (Botswana) and Otosirieze Obi-Young (Nigeria), in Africa in Dialogue:

A powerful rumination on the character of homophobia and the beginnings of misogyny, and on the forms of queerness assumable in pop culture.

“A Sense of Where We Are,” in Enkare Review:

Ten pieces of nonfiction, poetry and photography—by Alexis Teyie, Wairimũ Mũrĩithi, Carey Baraka, Silas Nyanchwani, Nduta Waweru, Wachira Njege, Amol Awuor, Sitawa Namwalie, Frankline Sunday, and Roseline Olang’—that form, with love and that anger that comes from love, a portrait of Kenya—its 2017 elections, its ethnic relations, its lack of political certainty. It is a literary magazine’s search for political clarity that we all owe gratitude.

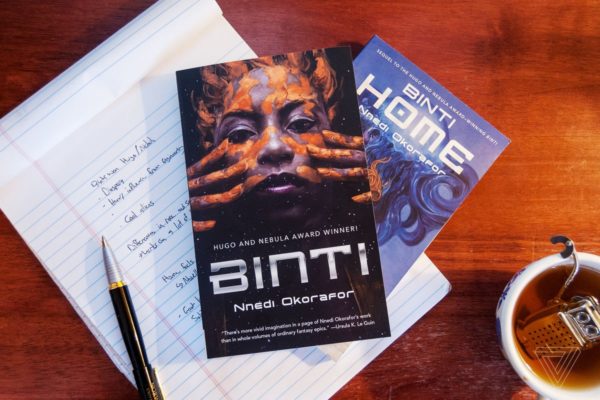

Nnedi Okorafor and the Fantasy Genre She Is Helping Redefine, in The New York Times:

In a year in which she blew from Fantasy Literary Superstar with a Cult Following to simply Literary Superstar, a profile detailing her interest in the otherworldy which has produced a catalogue of culturally-rooted, genre-defining fiction: the Wole Soyinka Prize-winning Zahrah the Windseeker (2006); the World Fantasy Award-winning Who Fears Death (2011), which is forthcoming as a HBO TV series; the Nebula- and Hugo Awards-winning Binti (2015)—all of which have won her such fans as Rick Riordan, George R.R. Martin, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Neil Gaiman.

“Untimely Meditations,” A Conversation by Taban Lo Liyong (South Sudan/Uganda) and Paul Mason (South Africa) and Stacy Hardy (South Africa), in Africa in Dialogue:

We are informed through the veteran’s beginnings in creative writing, through modernism and realism and what isn’t them, to Satre and Simone de Beauvoir and Nietzsche, to the politics of his generation of writers, and what Ayi Kwei Armah and Dambudzo Marechera signify, to the work of Ngugi. An archival supplement to our understanding of our literary culture.

“Binyavanga Wainaina and Me,” In Conversation with Diriye Osman (Somalia), in The Afrosphere:

A portrait of two iconic gay African writers, this video conversation, filmed in 2012 London by the Iranian director Bahareh Hosseini, is all warmth and generosity of spirit, without letting up on the intellectual power expected from such a match.

“Book’d: Ainehi Edoro,” in Afomaumesi.com:

One of those end-of-the-year interviews that are in fact perfect closers. From Walatta Petros’ 1672 Coptic hagiography The Life and Struggles of Our Mother Walatta Petros to recognizability in Petina Gappah’s Rotten Row (2016), to reading in a Lagos danfo, to why Jennifer Makumbi’s Kintu (2014) is the greatest historical fiction since Achebe, to why Chris Abani’s later novels are more fun, to the memorable endings of Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North (1967) and Nuruddin Farah’s Secrets (1998), to why we must all read J. M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians (1980) and Zakes Mda’s Heart of Redness (2000) and Jose Agualusa’s The Book of Chameleons (2004): Edoro’s expansive knowledge of literature and sense of presentation makes this an edible read.

A Wave of New Fiction from Nigeria, as Young Writers Experiment with Different Genres, in The New York Times:

Anchored in the scene-changing work of publishers Cassava Republic and its co-founder Bibi Bakare-Yusuf, and in those of Farafina, Parrésia and Ouida Books, a brief overview of contemporary books by Nigerian writers—Abubakar Adam Ibrahim’s Season of Crimson Blossoms (2015), Teju Cole’s Every Day Is for the Thief (first published 2007), Sarah Ladipo Manyika’s 1.7 million-selling In Dependence (2008) and Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun (2015), A. H. Mohammed’s 2.5 million-selling The Last Days at Forcados High School (2013), Yemisi Aribisala’s Longthroat Memoirs (2016), Leye Adenle’s Easy Motion Tourist (2016), Chigozie Obioma’s The Fishermen (2015), Elnathan John’s Born on a Tuesday (2015), Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay with Me (2016), and Lola Shoneyin’s The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives (2010).

“Everything Lost Will Be Given a Name,” A Conversation by Safia Elhillo (Sudan) and Alex Deuben (USA), in The Brooklyn Rail:

A discussion of her debut collection The January Children reveals how the late Egyptian music icon Abdel Halim Hafez serves as its centrepiece, a lens through which to interrogate questions of affection, language, and race.

“The Disappearances of Women,” A Conversation by Titilope Sonuga (Nigeria) and Gaamangwe Joy Mogami (Botswana), in Africa in Dialogue:

An appraisal of the female experience in a world that forces invisibility on them, and of the ways through which we channel pathways to our truest selves.

“2010s: The Decade of African Literary Expansion,” Brittle Paper Anniversary Conversation with Beverley Nambozo Nsengiyunva (Uganda), Gbenga Adesina (Nigeria), Gaamangwe Joy Mogami (Botswana), Kiprop Kimutai (Kenya), Sibongile Fisher (South Africa), and Wale Owoade (Nigeria), on Facebook:

Six of the continent’s notable writers, editors and founders came together on Facebook to gift us this engaging and candid discussion of the state of African literature in the 2010s. From their experiences founding important platforms to the new wave of remarkable poetry sweeping across the continent, from the role of the Internet in breaking out writers to the importance of professional support systems, from their creative and administrative processes to the funding link between the arts and politics, from the expectation that prizes should reflect the literary landscape to the future of literature and pop culture: A highlight of the year.

Otosirieze : Statement on Leaving Brittle Paper - April 15, 2020 10:58

[…] instantly began regular blogging, launching an annual list of The Notable Pieces of the Year (2016, 2017, 2018). By March 2017, I was asked to temporarily be Acting Editor and take over the full running […]