Last week, we announced our inaugural Brunel Prize Poems Review Series. Our reviews of the poems shortlisted for the 2018 Brunel International African Poetry Prize begins with readings of entries by Nour Kamel and Gbenga Adeoba, by Brittle Paper writer Kanyinsola Olorunninsola.

NOUR KAMEL

Nour Kamel is a writer based in Cairo, Egypt. She also works as an editor helping to launch homegrown magazines and online publications, and is a Winter Tangerine workshop alumnus and advisor. She received her a degree in American and English literature from the University of East Anglia and also studied at the University of Mississippi. Kamel writes about identity, language, sexuality, queerness, gender, oppression, femininity, trauma, family, lineage, globalisation, loss and food.

On “How Lineage Works,” “Woman Looking for the Disappeared Disappears on Way to Conference on Disappearances,” and “Raet Meets Me at Behoos”

look, people just go missing here

what could be more female than that

to go missing with no one to claim you

were ever there

Away from home and on this journey, we encounter a fog and disappear into the vast emptiness of the wild. With no way of protecting either our names or our bodies, we become the very definition of the victims of lineage and oppression which Kamel writes about vividly.

In “Woman Looking for the Disappeared Disappears on Way to Conference on Disappearances,” she notes the disappearing act which girls have inadvertently become experts at, which brings to mind the systemic disadvantages women are subjected to. At the risk of sexual assault and violence, women are often seeking safe spaces just to be able to breathe. “What is the function of femininity except survive in danger?” she asks. Though the poem seems to dive headfirst into overt pain-mongering, the poet’s control keeps it from going off the rails, ensuring that the anguish is carefully packaged and mailed to the doorstep of the reader’s conscience. Must women always live in fear? Kamel does not think so. And she is not done fighting for herself, even if you are:

I’ve never walked a street alone

forgetting who I am but goddamn

I’ll fake my safety til they believe it toountil trust is not just family

life is had above ground

love can be in color

In “How Lineage Works,” Kamel’s obsession with lineage is painted as a multi-coloured portrait of complexity and confusion. She writes about her [alleged] connection to different roots with a tone of mild skepticism. This soon delves more to the practical, with a relationship with a half-sister coming to the fore.

“Raet Meets Me at Behoos” is a reclamation of power. Rather than see herself only as a victim of the world’s violence, Kamel invokes the raging-hot might of the Egyptian goddess, Raet-Tawy. Drawing inspiration from something divine, Kamel’s poet-persona sees herself as something truly powerful, a literal sun-god[dess].

The three poems can be read HERE.

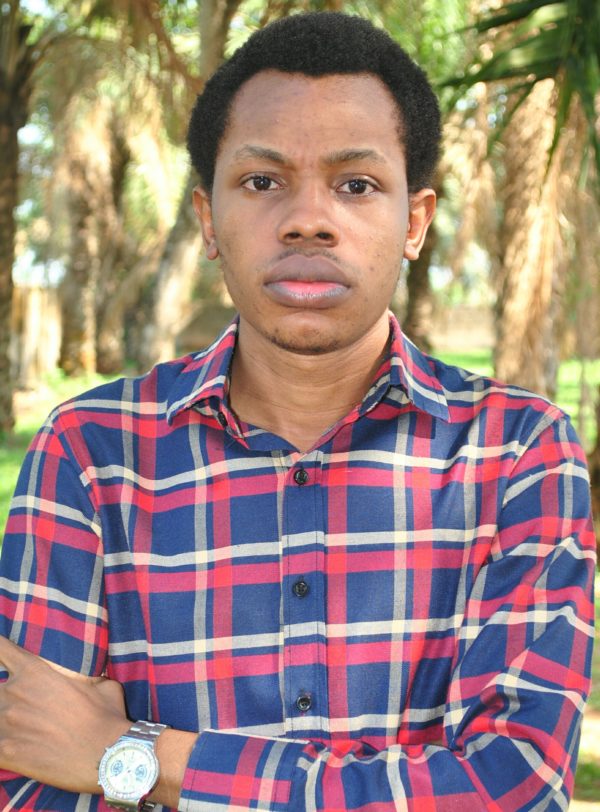

GBENGA ADEOBA

Gbenga Adeoba is from Nigeria, where he lives. His writing explores themes of memory, transition, and the intersections between the imaginative and the historic. His poetry has been featured or is forthcoming in Elsewhere Lit (Anthology of Contemporary African Poetry), agbowo.org, Notre Dame Review, Prairie Schooner, Oxford Poetry, Poet Lore, Salamander, Pleiades, and others. Follow him @_Snowburl.

On “Seafarers,” “Resurrection,” and “Eclipse”

It was a soft, fluid tune:

the tender draw of water, a rare liquid craft—

the sea, keen, humming a promise of calm,

urging us to draw closer, to unlearn

all we thought we knew about the posture of water.

It begins at sea with Gbenga Adeoba’s powerful trio. With jarring urgency, his words capture the tragedy of a historical evil. He discusses the battering of the black body by “smugglers.” He exquisitely takes the sea into account, implicating it in the conspiratorial degradation of the soul of the black man. This bold narrative fits in with the myth of black people being afraid of water, perhaps because of this betrayal.

Adeoba is not the first to employ this particular sentiment in a dissection of black history. But what he does well is highlight it to the point where the survival—or at least the illusion of it—of a black man, from the hands of the captors, from the murdering hands of the sea, is indeed a miracle, a biblical wonder. He humanizes the victims, forcing you to mourn their lost dreams, their lost memories, their lost selves.

In “Eclipse,” the poet makes one ponder upon the, well, eclipse of the black man’s future. Both in the particular and generic sense. The legacy of slavery is the disruption of history, an eclipse of a nascent sun which once threatened to burn bright. He notes the heaviness of the African immigrant experience, particularly when you do not go into it willingly:

What binds us now is a known fear,

a kinship of likely loss, the understanding that we, too,

could become a band of unnamed migrants

found floating on the face of the seaor swept ashore by wave upon wave

on a beach west of Tripoli.

With words having both the capacities to be calm as still water and sweeping as a flood, Adeoba takes you on a boat ride of linguistic celebration. But it is not the kind that ends in any particularly gleeful fashion. The last song is that of a sad music of “whispers,” of the “body speaking to itself”: is this all there is to being black? Being a perpetual victim of loss, of fear, of new lands? And of the sea?

The three poems can be read HERE.

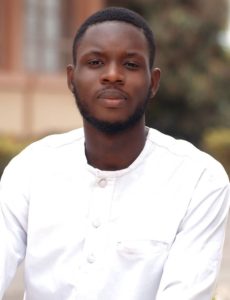

About the Reviewer:

Kanyinsola Olorunnisola is a poet, essayist and writer of fiction. He writes from Ibadan, Nigeria. His debut poetry chapbook, In My Country, We Are All Crossdressers, is forthcoming from Praxis Magazine. He is the founder of the literary movement, SPRINNG, Society for the Promotion, Revitalization, and Improvement of the New Nigerian Generation. He loves experimental literature, pop culture, and Nigerian jollof rice.

Kanyinsola Olorunnisola is a poet, essayist and writer of fiction. He writes from Ibadan, Nigeria. His debut poetry chapbook, In My Country, We Are All Crossdressers, is forthcoming from Praxis Magazine. He is the founder of the literary movement, SPRINNG, Society for the Promotion, Revitalization, and Improvement of the New Nigerian Generation. He loves experimental literature, pop culture, and Nigerian jollof rice.

Nan Carter May 14, 2018 15:41

I would buy their poetry. In future reviews please let us know exactly titles of the books these poems are included in. Or exactly where on the internet the poems can be found. Thanks Nan carter