Publication Date: TBA.

Publisher: Cassava Republic Press.

Number of Pages: 342.

***

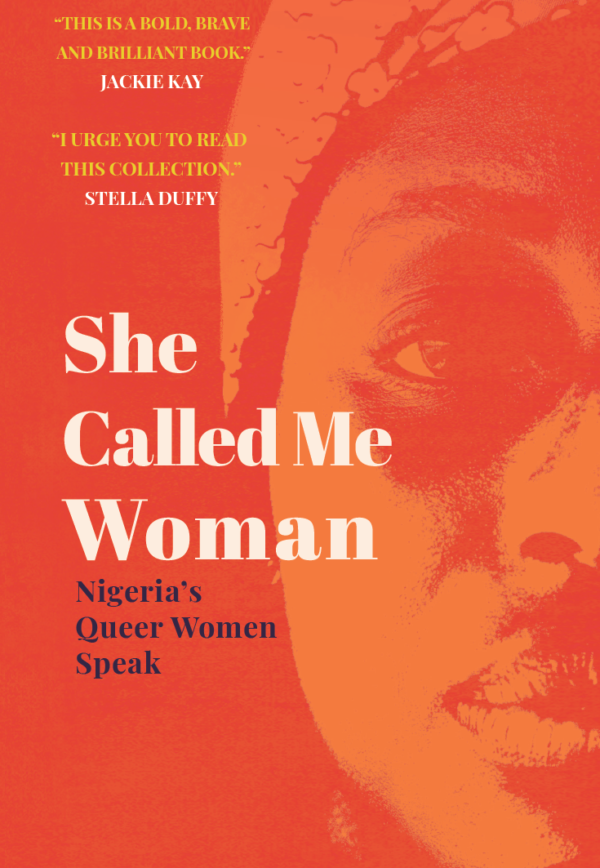

Art is most beautiful when we find pieces of ourselves in it, when it resonates with our realities or what we want our realities to be. She Called Me Woman: Nigeria’s Queer Women Speak transcends beautiful. This history-making opus will shake the tables our collective homophobia—internalised and externalised—sits on. Its daringness will embolden us to take off the heavy, dark, velvety silence that has draped talks of Other sexualities.

She Called Me Woman plumbs the depth of what it feels to be queer, a woman, and Nigerian, by revealing these realities via 25 raw, blatant, and intimate stories told in the first-person. These brave women from different geo-political zones in Nigeria and the Diaspora unapologetically tell a part of our collective truth (a truth people cover in a bid to validate homophobia by saying, “Being gay is not African”) through subjects such as sexual violence, love, child abuse, domestic violence, forced outing, alcohol and drug abuse, grief, rape, and abortion.

In “Everyone in J-Town Is Now a Lola,” AG from Plateau recounts that her earliest memories of being attracted to a girl was when she was in Primary Four. “Whenever I was with her, I was open. I could talk. I could share my emotions. I didn’t know what I was doing. I didn’t know it was bad. I didn’t know what I was doing was called attractions or emotions.” In “To Anyone Being Hated, Be Strong,” BM, who is from Plateau also, says, “Many of the girls at my school are now married with children but they still see other girls. Some are scared to even try it again but want to.”

These stories come from an honest and emotional place. They will pull you in, shock you, and haunt you long after you have stopped reading. “For a number of our narrators, opening up was a cathartic experience. Many shared experiences they had never previously spoken about,” one of the editors writes in the Introduction.

We are immersed in tales of fetishisation disguised as acceptance, hope, grief, heartache from lovers, joy, triumph in the face of hostility, and a whole lot of strong feelings. HK from Abuja writes, “I live with my partner now. We see each other every day, except when she is in Lagos. For the first time ever, I have someone taking care of me. I wake up in the morning and she is there with a cup of tea. It feels good to have someone there. I feel really loved by her.”

We discover how these brave women cope with melding religion and sexuality. In “I Pray That Everyone Has Forgotten,” TQ states: “I’m a devout Christian. Anything I do, I put God first. I don’t play with prayer. But it’s difficult.”

We learn of internalised homophobia, how people employ aggressive homophobia to cope with their sexuality. KZ, 40, from Lagos reveals: “You can’t tell me that our Nigerian leaders have not met any gay people. They know the gay people in this country. Maybe 70 per cent of this country is gay or bisexual but they will not come out. I have a friend who is married. She goes to events and I know about three women she has dated over the years. But on her Facebook page, she is so homophobic! She is covering up and that is what everybody is doing.”

We live vicariously through them as they strive to thrive in an unfair society that is prejudiced against women. We learn how the misfortune of belonging to a lower social class heightens the chances of facing sexism and homophobia. Anyone who does not understand the intricate workings of intersectionality will find this book enlightening. These stories are all shades of resilience and determination to attain the highest expression of one’s self in the cruel and ugly face of hate.

In fiction, few female writers have narrated stories about what it entails to be Nigerian, queer, and a woman, most notably Chinelo Okparanta, in Happiness, Like Water (2013) and Under the Udala Trees (2015), and Yvonne Fly Onakeme Etaghene, in For Sizakele (2015). But there is something confrontational, compelling, when you thumb through pages of non-fiction to experience reality from a real person’s perspective. She Called Me Woman joins the Unoma Azuah-edited Blessed Body: The Secret Lives of LGBT Nigerian Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (2016) in this group. She Called Me Woman is a documentation for our descendants. They would know that difference is normal, that humanity has a handful of hues. People would be inspired to embrace themselves. Queer people will understand that queerness should come with no apology—there is no need to justify or explain why you love who you love.

Here is a bold statement: We are brave, we are bruised, and we are who we are meant to be. We are queer; we are here. This is us!

About the Author:

CISI EZE is a Lagos-based journalist, writer, comic artist, and graphics designer. A media and justice fellow of the Bisi Alimi Foundation, she feels strongly about LGBT+ rights, feminism, gender issues, and mental health, and this is expressed through her articles as a guest contributor on Bella Naija; her blog, Shades of Cisi; a podcast she co-presents, “We Said It”; and an online radio show, “Stirring the Waters.” Aside these, she has works on Kalahari Review, Holaafrica, Mounting the Moon poetry anthology, Outcast Magazine, Rustin Times, and 14: An Anthology of Queer Art, Volumes 1 and 2. Cisi’s art challenges existing societal norms.

Love in Literature: Reading Love in Literature - Cassava Republic Press January 08, 2024 17:12

[…] Eze, in a review of She Called Me Woman published in Brittle Paper writes, “these stories come from an honest and emotional place. They will pull you in, shock […]