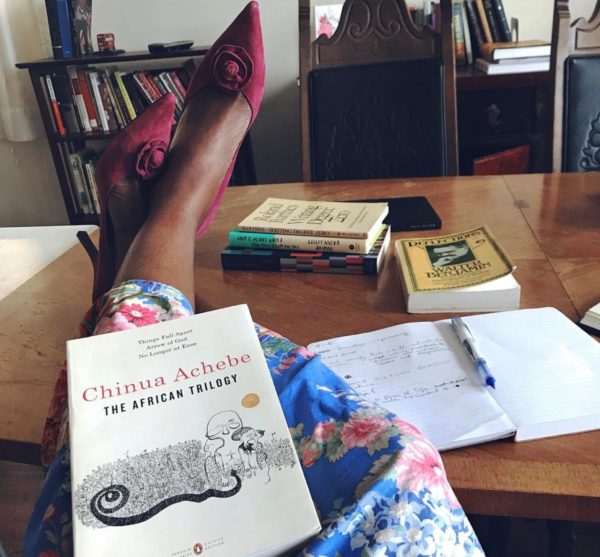

Sometime in April, I received an email from the BBC Culture’s editor to nominate five stories that I believed had “the most impact on shaping ideas and changing minds through history.” The same invitation had been sent to other writers, critics, and academic the world over. 108 people from 35 countries responded, including myself. On May 22, the top 100 selections were published and revealed a few surprises. Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart came up at #5 ahead of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, The Harry Potter novels, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Kafka’s Metamorphosis, and (this is the best part), Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Talk about poetic justice! It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Things Fall Apart was #1 on my list of five. What is certainly worth reflecting on is why other critics agree with me that Achebe’s debut novel has done more in shaping the world, as we know it, than Shakespeare’s classics.

Culture lists of these sort are simultaneously trivial and significant. They are trivial in the sense they do not represent popular opinion. What 108 people think of literature counts for very little. But what these kinds of top 100 lists lack in statistical value they make up for in cultural value. They are problematic for sure. But we also can’t discount them, in part, because they allow texts to circulate in interesting ways, and they influence readers to reevaluate the value they ascribe to texts.

For example, Things Fall Apart’s interesting position on the BBC list certainly reopens the question of Achebe’s monumentality in world literature and the African literary tradition. Things Fall Apart holds a fascination for readers. It still captivates the popular imagination and holds readers in thrall such that 60 years after its publication, the novel continues to seep deeper and deeper into our literary unconscious. But the truth is that while critics and readers agree that Achebe’s first novel is special, there continues to be considerable disagreement over how special the book is and the nature of this specialness.

To identify what captivates us about Things Fall Apart, we have to begin with one of the most outrageous claims ever made about Achebe. In his 1991 book on Achebe and in an essay published 10 years later, Simon Gikandi claims that Achebe invented African literature with the publication of Things Fall Apart. First of all, you might wonder, African literature is neither a light bulb nor a nail clipper, so how can we even think of it as something that is invented? Second, how can we possibly grant that honor to one book written in 1958 by a 25 year old kid? But Gikandi’s claim appears crazy only because it is so easily misunderstood. Things Fall Apart marks the starting point of African literature not because it is the first or best African narrative but because of the unique role it has had to play in global literary discourse.

If you think Gikandi’s claim is outrageous, you are probably one of those people who scoff at the idea of Achebe as the Father of African literature. Well, you’re in good company. In the weeks following Achebe’s passing, Wole Soyinka felt compelled to ask people calling Achebe the father of African literature: “have you the sheerest acquaintance with the literatures of other African nations, in both indigenous and adopted colonial languages? What must the francophone, lusophone, Zulu, Xhosa, Ewe literary scholars and consumers think of those who persist in such a historic absurdity? It’s as ridiculous as calling WS father of contemporary African drama!”

Soyinka is spot on, except for one small thing. This is, of course, not to defend the antiquated and rather sexist concept of granting African literature a father but to highlight a small point, which Soyinka misses, about the idea of Things Fall Apart as starting point.

Soyinka, like many of Gikandi’s critics, confuse African literature for African texts. This is a common mistake. We tend to imagine aesthetic categories like “British literature,” “poetry,” or “the novel” as natural categories. As a result, readers would often imagine African literature as something that has always existed. Again, this is based on a faulty reasoning where you confuse African literature as an aesthetic category and individual texts associated with the historical, geographic entity called Africa. But these are two different things. There has always been writing, narratives, texts, etc. in Africa, but there has not always been African literature. In fact, the term “literature” as a way of organizing and giving value to texts has not always existed. Homer did not think of The Odyssey as literature because literature is an invention of modernity. Soyinka is right. Africans have been telling stories for hundreds of years, thousands, if we accept Abiola Irele’s claim that the Egyptian Book of the Dead is the first African text. But the gesture of organizing this vast body of texts into a category called African literature with a specific history, market value, aesthetic concerns, and global circulation is a very recent event. For Gikandi, that event is the publication of Things Fall Apart.

What is African literature? It is simply a way we organize a bundle of texts. It is a term we use when we wish to draw attention to what a set of texts have in common. It tells us that there are a set of stable attributes that we can apply to a body of text in spite of the differences that make each text a distinct entity. African literature is, thus, a universal category. But universals don’t come out of nowhere. A universal concept is born of a particular entity that is so powerful that it can serve as an example. Things Fall Apart is that book. It was never the first African story, but it was the first to make an example of itself. Like a magnet, it pulled together texts scattered across space and time into the ensemble called African literature. In so doing, it influenced not only what was around it, but what came before it and what was yet to come.

Things Fall Apart has this looming influence over our thinking, an influence that we can’t seem to shake off by simply denying it. Things Fall Apart is this idea that we are always affirming or critiquing, loving or hating, embracing or disavowing. When you write about African literary history, you have only two choices: begin with Achebe or don’t begin with Achebe. Either way, Things Fall Apart is the foundation you have to stand on or reject. Ask Mukoma wa Ngugi. His new book The Rise of the African Novel is bold in its attempt to dispel the enchantment of Things Fall Apart as some kind of beginning. But, guess what. The book begins where every other historiographical work on African literature begins—Things Fall Apart! The opening sentence reads: “Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart has been translated into over 50 languages.” The irony is that the very gesture of de-mythologizing Things Fall Apart confirms the monumentality of Things Fall Apart and exposes Mukoma’s reliance on this monumentality to give structure to his own account of the African novel. As Chris Abani reminds us, to be an African writer or thinker is essentially to be trapped between “resisting [Achebe]” and “writing towards [Achebe].”

There you have it. Things Fall Apart does not have to be the first to be the historic beginning of African literature. History is not chronology. Chronology is the way events succeed each other in a timeline. History is the way we place emphasis on one event over another. Sundiata’s story may have come before Things Fall Apart, but Things Fall Apart put Sundiata’s story on the map. That is whyThings Fall Apart will continue to grow in significance with each passing decade. Until we find another book or text that orients the existence of African literature the way Things Fall Apart does, we will never be able to exorcise its influence on our thinking.

Ainehi Edoro June 04, 2018 07:47

@Eddie. "Just one thing, more influential than Shakespeare? Abeg, you really think so? I’m grinning from ear to ear." Lol. But then my questions to you is: did Shakespeare invent African literature?