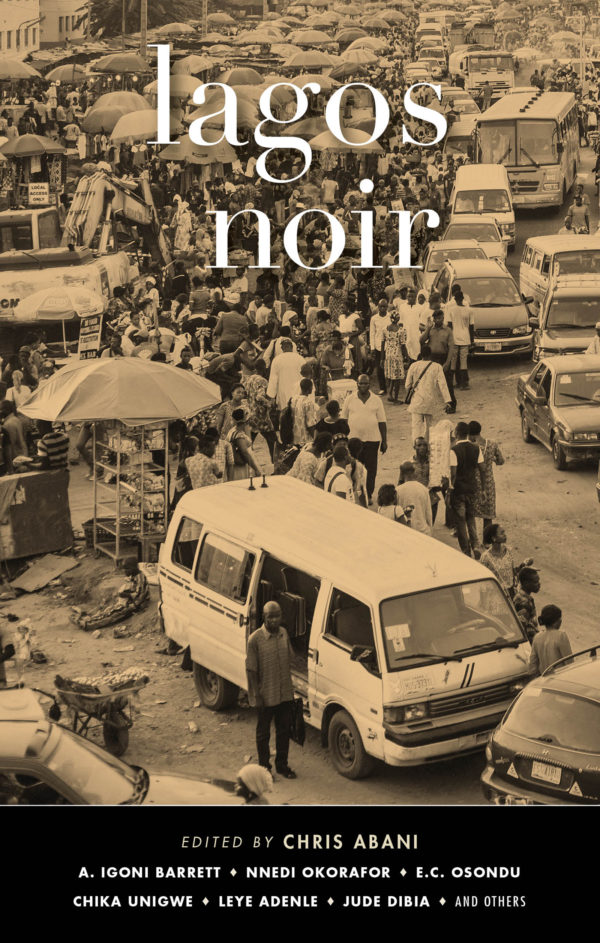

Lagos: city of myth. A sprawling megalopolis, home to 21 million souls and 21 million stories. Contemporary Nigerian fiction returns often to the city as a place for inspiration, but genre crime remains the best lens for interrogating urban locales. The crime writer is attracted to the underbelly, places far from the tourist trail, the sewers and gutters, the kinds of characters never mentioned in polite society. I have written elsewhere about the growth of the contemporary crime novel in Nigeria, but now we can add short fiction to the mix.

The Lagos Noir anthology has a stellar cast of award-winning Nigerian authors who ply their trade in multiple genres, each tasked with placing just one distinct neighbourhood in the city under the microscope. Nigerian crime fiction is experiencing something of a modern revival akin to the Golden Age of Crime Fiction, albeit with distinct national peculiarities, many of which can be discerned in this one anthology. Jude Dibia’s opener, “What They Did That Night,” features the only clean cop in the collection: Corporal Gabriel. He investigates a string of murders and robberies in the upmarket district of Lagos Island only to find that his fellow officers are on the make. It takes his wife and superiors to make him see that by being upright he is upsetting a delicate balance and the police department is no place for an honest man.

A distinct theme in the anthology and Nigerian crime fiction in general is that the police are just another criminal gang. Underwriting conduct in Lagos is an intricate set of unwritten rules that determine the flow of bribes that grease the wheels of the city’s economy. We learn in Chika Unigwe’s “Heaven’s Gate” that:

“Lagos police and commercial drivers had an unwritten agreement: the latter were fair in the amounts of bribes they gave and the former never assaulted them.”

The authors in Lagos Noir show a distinct disinterest in traditional crime detection narrative tropes, whodunnits and howdunnits. The truth can only upset the fragile social compact necessary for survival as experienced by Detective Okoro in Chris Abani’s “Killer Ape.” Set in the expat community of newly postcolonial Nigeria, Okoro, whose policing methodology seems to depend on wisdom gleaned from Sherlock Holmes stories, investigates the murder of Gordon Parker, a white Brit in Ikoyi. The results of his investigation lead him to the conclusion that it is better to fudge the case as the fallout would be catastrophic. And staying among the wealthy Lagosians, the reader encounters visceral fear and loathing for their less fortunate compatriots, especially the servants who share their homes.

Sarah Ladipo Manyika’s “The Swimming Pool” is a Victoria Island revision of Murder on the Orient Express, with the spotlight on the wife, the daughter and the maid. It ties in perfectly with Wale Lawal’s “Joy” in which the mistress must contend with the younger maid determined to usurp her place. In both Manyika and Lawal’s stories, the fragile line between master and servant creates a friction that can only drive the narrative towards murder most foul. Mansions and book clubs and imported luxuries are no insulation from the grit of Lagosian life which pours in through the cracks and overwhelms any pretensions of safe havens.

One is continually impressed by the diligence and industriousness of the criminals in this anthology. Pemi Aguda’s “Choir Boy” blurs the line between cops and robbers when a whole bus is kidnapped for an extortion racket. One of the key gang members is even dressed up in police uniform. This story dovetails neatly with Leye Adenle’s “Uncle Sam” in which another white Brit, Dougal, finds himself at Murtala Muhammed International Airport after receiving emails which may or may not be a 419 scam about a potential inheritance. Adenle’s story has a neat twist with the arrival of a man claiming to be the director of Nigeria’s anti-corruption department. One usual theme in Nigerian fiction, both literary and crime, is how utterly inept and naïve Westerners are when it comes to navigating Nigerian society. Unaware of the complex unwritten rules, they are fair game for the numerous sharks operating in the murky waters of the city.

Nnedi Okorafor’s contribution to this anthology, “Showlogo,” has one of its most charismatic lead characters. The story opens with a body falling from a plane in Chicagoland and then works its way back to the how.

Religion and vice are other recurring preoccupations in the anthology, revealing the disastrous effects of the prosperity gospel in Africa. Some of the stories strain the definition of what constitutes a “crime story,” especially A. Igoni Barrett’s “Just Ignore And Try To Endure” and Uche Okonkwo’s “Eden.” In these stories, the breaking of the social compact—whether it is in a landlady withholding the keys for two weeks after a tenant is due to move in or parents carelessly leaving pornography VHS cassettes for children to access—drives the narrative. It is in these sub-broken window transgressions that the reader is asked to extrapolate complex conclusions.

Lagos Noir is a quality inclusion to Akashic Books’s award-winning city noir series which has now run to almost 100 books set in many of the world’s major metropolitan centres. The quality of the prose is top-notch, the narratives and their locations are vivid and engaging. This anthology stands out because of its unique approach to crime and punishment, and its intense focus on the sociological aspects of crime in one of the world’s largest, fastest growing and most complex regions. Lagos Noir is a must-read for crime lovers looking for something different to read in a highly saturated market.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions