Peter Kimani’s novel Dance of the Jakaranda—published in the UK by Saqi Books—makes for an enlightening and beguiling read. At one level, it is the story of Kenya’s transition from British colonial rule to independence in 1963, told from the perspectives of a diverse range of protagonists. But as the narrative proceeds, Kimani gradually adds layers of tantalising texture to this larger tale that ultimately produces a hybrid vision shot through with competing histories and illusive identities.

The novel opens with the maiden voyage of the infamous train line known as the Lunatic Express in 1901, which was built in the area formerly known as the British East Africa Protectorate. The railway initially ran from Mombasa on the coast to the shores of the great lake christened Victoria by the British explorer John Hanning Speke in 1858. The Lunatic Express was so-named by its London architects, who the novel reveals did not know “where the rail would start and where it would end, for nothing of value was to be found in the African wilds.” Among the first passengers to ride on the railway are Ian Edward McDonald, the British colonial officer who oversaw the railway’s construction, and Reverend Richard Turnbull, an English missionary based in the region. While these characters’ perspectives on the train line dominate the opening passages of the novel, the narrator also gestures to a variety of alternative viewpoints, which begin to disrupt that imperial gaze and lay bare its seismic consequences.

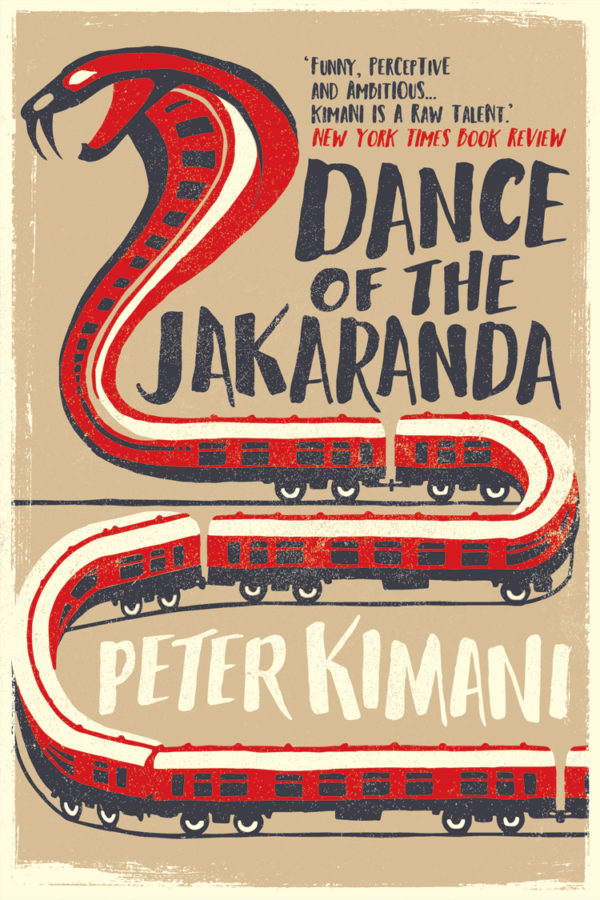

When the reader first encounters the railway, it is not portrayed from the standpoint of the colonisers but from that of the local villagers. They see it as a “monstrous, snakelike creature whose black head, erect like a cobra’s, pulled rusty brown boxes and slithered down the savannah.” Such conception of the Lunatic Express as a grotesque and menacing impostor in the land, rather than as a glorious feat of colonial enterprise, lays the blueprint for the novel’s radical reappraisal of Kenyan history. As the narrator suggests, this is a “land where myth and history often intersected,” and at every stage the narrative strives to offer a deeper kind of truth about its subject. It refuses to give precedence to a single or authoritative voice when more are there to be heard.

Kimani has revealed in interviews that the train line functions as the large narrative device underpinning the broader structure of the novel. While this creative decision is clearly borne out in the text, it is also the case that its cognate laying of tracks and layering of perspectives are juxtaposed, and further complicated, by the construction of the titular Jakaranda Hotel. This architectural landmark was built by McDonald in the area called Nakuru after the completion of the railway as a failed Monument to Love for his estranged wife Sally. Over the course of the novel, it becomes the site of multiple transformations and chance encounters.

It is revealed that after McDonald was rejected by Sally, the house of love turned into “a veritable heart of darkness,” which burdens the building—and the wider narrative—with the spectre of Joseph Conrad’s fictionalisation of colonial Congo in Heart of Darkness (1899). A less assured writer might have succumbed to this most portentous of literary references by overbearing the narrative with allusions to its vexed legacies. While Kimani clearly invokes Chinua Achebe’s famous appraisal of Conrad’s novel as racist and dehumanising, he does not fall into the trap of merely ventriloquising this thesis. Instead, his Conradian vision of McDonald’s house quickly gives way to a more generative and hybrid formation:

And when the doors and the windows to the house were finally opened, the villagers were surprised to see cows rearing their big heads in the doorway. That’s when the edifice was converted into a farmhouse that later gave way to the segregated social establishment, which further gave way to the multicultural outfit named the Jakaranda, the letter k for Kenya replacing the c in the jacaranda that McDonald said sounded “colonial.”

Now, on the cusp of the new republic and a new dawn for its multicolored citizens, the Jakaranda was about to acquire a new identity, yet again (63-64).

In this way, the hotel—which in its name and purpose is marked by processes of revision sparked by the colonial encounter—provides the dramatic backdrop for the novel’s other major narrative arc. For it is during a blackout at the Jakaranda Hotel in 1963 that the popular local musician Rajan, a relation of the Indian immigrant-turned-railroad surveyor and entrepreneur Babu Rajan Salim, receives a kiss laced with lavender from a mysterious woman before one of his performances.

This chance but providential encounter sets off a chain of events throwing together the stories of McDonald, the Salims, the stranger and Turnbull, as well as the wider Kenyan society. As the narrative twists and turns, sliding forward and backward in time, in slow but deliberate revelation, its shifting style becomes embodied in the communal dance of the Jakaranda, also called “mugithi, the train dance, bringing onstage the stories that Rajan’s grandfather Babu had narrated about his life building the railway.” Another hybrid reimagining of the local population’s shared and febrile histories, it gives organic form to an array of legacies, mediating between experiences of conquest, subjugation and brutality on the one hand, and acts of co-operation and intimacy on the other.

Crucial in these explorations of Kenyan history is the thorny issue of identity. As Rajan reflects on the possible background of the kissing stranger—later revealed to be Mariam, a figure who crucially connects the stories of McDonald, Turnbull and Babu—he offers a meditation on its problematic and slippery nature:

After all, humans do not wear identities on their faces. Where would he place her in a land where dozens of communities existed? And how could he describe himself anyway? […] And would it be accurate to describe himself as Indian when his only encounter with the subcontinent was through the stories he had heard from his grandparents? He realized to his horror the perils of history and the presumptions that come with symbols (43).

Although the novel tackles this problem head on, straining to articulate an idea of Kenyan identity at the cusp of the nation’s independence, it is in its refusal to define who is and who isn’t Kenyan that it fulfils its promise as a profound work of historical complexity.

Ultimately, Dance of the Jakaranda is a sophisticated excavation of Kenya’s longer development: one which not only humanely portrays some of the most painful barbarities committed across the African continent in the name of colonialism, but also contends with challenges that still face the country. But it is also the story of an unlikely family of souls brought together under strange circumstances to forge a community. It is a testament to Kimani’s searing vision that he is able to strike such a fine balance between personal and shared perceptions of these tumultuous events, while also having the courage to trace those hybrid histories along unfamiliar tracks.

READ: Book Excerpt | Peter Kimani’s “Dance of the Jakaranda”

About the Reviewer:

MATTHEW LECZNAR is a PhD student at the University of Sussex, researching artistic legacies of the Nigeria-Biafra war (1967-70). By placing literary sources in dialogue with different cultural responses to the war—in films, photographs, paintings and plays—his thesis probes the ways artists have creatively remembered and reimagined the Nigeria-Biafra War. As part of his studies, Matthew has conducted a research fellowship at the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and participated in the Aké Arts and Book Festival in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Matthew has published articles in Research in African Literatures and Celebrity Studies as well as reviews for The Con Mag and Africa in Words.

MATTHEW LECZNAR is a PhD student at the University of Sussex, researching artistic legacies of the Nigeria-Biafra war (1967-70). By placing literary sources in dialogue with different cultural responses to the war—in films, photographs, paintings and plays—his thesis probes the ways artists have creatively remembered and reimagined the Nigeria-Biafra War. As part of his studies, Matthew has conducted a research fellowship at the National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and participated in the Aké Arts and Book Festival in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Matthew has published articles in Research in African Literatures and Celebrity Studies as well as reviews for The Con Mag and Africa in Words.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions