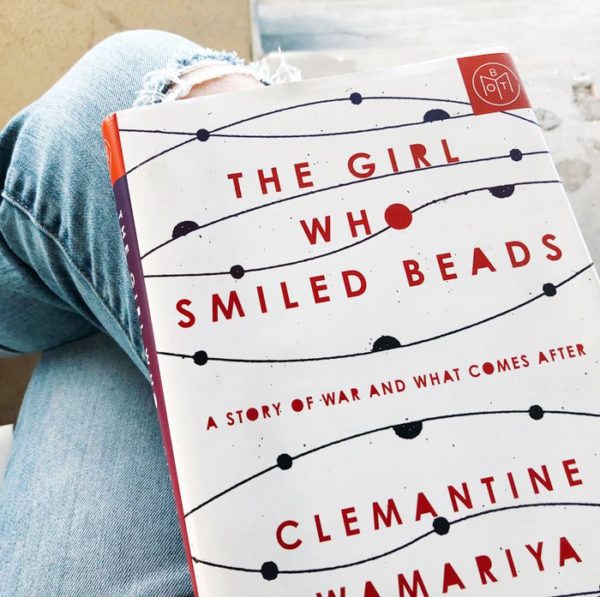

Clemantine Wamariya first came to our attention in 2015 with her essay in Matter titled “Everything Is Yours, Everything Is Not Yours” and co-written with Elizabeth Weilis. The essay was featured in our reflection on the fictionalisation of violence, and it is exciting to see that it had always been part of a book-in-progress. The Girl Who Smiled Beads: A Story of War and What Comes After is a devastating, beautiful memoir of Wamariya’s survival of the Rwandan Genocide of 1994.

The book, released by Penguin Random House on 24 April, 2018, is co-written with Elizabeth Weilis, a writer-at-large for The New York Times Magazine. It follows Wamariya from six years of age as she and her 15-year-old sister flee the genocide, spend six years migrating through seven African countries, before being granted refugee status in the USA, where she is taken in by a family and graduates from Yale.

Here is a description from its publishers, Penguin Random House:

Clemantine Wamariya was six years old when her mother and father began to speak in whispers, when neighbors began to disappear, and when she heard the loud, ugly sounds her brother said were thunder. In 1994, she and her fifteen-year-old sister, Claire, fled the Rwandan massacre and spent the next six years migrating through seven African countries, searching for safety—perpetually hungry, imprisoned and abused, enduring and escaping refugee camps, finding unexpected kindness, witnessing inhuman cruelty. They did not know whether their parents were dead or alive.

When Clemantine was twelve, she and her sister were granted refugee status in the United States; there, in Chicago, their lives diverged. Though their bond remained unbreakable, Claire, who had for so long protected and provided for Clemantine, was a single mother struggling to make ends meet, while Clemantine was taken in by a family who raised her as their own. She seemed to live the American dream: attending private school, taking up cheerleading, and, ultimately, graduating from Yale. Yet the years of being treated as less than human, of going hungry and seeing death, could not be erased. She felt at the same time six years old and one hundred years old.

In The Girl Who Smiled Beads, Clemantine provokes us to look beyond the label of “victim” and recognize the power of the imagination to transcend even the most profound injuries and aftershocks. Devastating yet beautiful, and bracingly original, it is a powerful testament to her commitment to constructing a life on her own terms.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions