Most of the best-known Africa-set African novels of the last five years are works of historical fiction: from Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor’s Dust (2013), from Kenya, and Jennifer Makumbi’s Kintu (2014), from Uganda, to Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Udala Trees (2015), from Nigeria, Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (2016), from Ghana, Peter Kimani’s Dance of the Jakaranda (2016), from Kenya, Haruna Ayesha Attah’s The Hundred Wells of Salaga (2018), from Ghana, and Novuyo Rosa Tshuma’s House of Stone (2018), from Zimbabwe. While a slew of other notable novels deal with either the present, the recent past or the fantastical—NoViolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names (2013), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah (2013), Taiye Selasi’s Ghana Must Go (2013), Chigozie Obioma’s The Fishermen (2015), Petina Gappah’s The Book of Memory (2015), Imbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers (2016), Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay with Me (2016), Uzodinma Iweala’s Speak No Evil (2018)—the first set of books are focused on the deep past not just as a setting but as an arena for reconstruction.

In an essay for Los Angeles Review of Books, titled “Reclaiming Africa’s Stolen Histories Through Fiction,” Lizzy Attree highlights the novels by Owuor, Makumbi, Kimani, Attah, and Tshuma in explaining why this is so, how it has been so.

Here is an excerpt.

ARE WE ON the cusp of a new age of African literature? If so, the key to new novels from African writers seems to be the fresh use of historical fiction to articulate a new future.

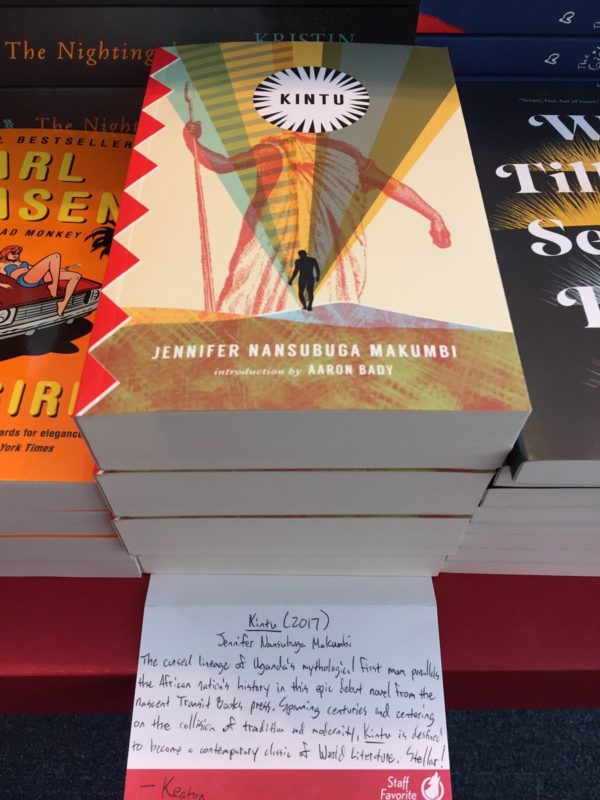

South African writer Marlene van Niekerk’s 2004 masterpiece Agaat (first translated into English from the Afrikaans as The Way of the Women by Michiel Heyns in 2006) is a candidate for the Great African Novel. Her second novel, it resonates far beyond the seminal Triomf (1994), and went unmatched for that title until Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu was published in Kenya in 2014. Winner of the Kwani? Manuscript Project (as The Kintu Saga, of which I was a lucky pre-judges reader), Makumbi’s novel is a Ugandan One Hundred Years of Solitude, a family saga that reaches back into that country’s history with an assurance and readability that makes its historical depth feel light as water. The wide acclaim it received in East Africa led to its publication in the United States by Transit Books in 2017 (with a controversially “unnecessary” introduction by Aaron Bady) and, in March 2018, a prestigious Windham-Campbell Prize, an award worth $165,000. Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor’s Dust, also published in 2014 (by Knopf in the United States), provokes a similar excitement.

In that moment, it felt as if African writers were taking on big topics and writing with such beauty and complexity that surely it signalled just the kind of coming of age that Nigerian poet and novelist Ben Okri hankered for in his December 2014 Guardian article “A mental tyranny is keeping black writers from greatness.” In the much-criticized think piece, Okri notes, “Great literature is almost always indirect […] [it] is rarely about one thing. It transcends subject.” But don’t Agaat, Kintu, and Dust transcend subject? Isn’t this the secret to their greatness? Didn’t these magnificent writers take on historical topics that demanded this transcendent treatment?

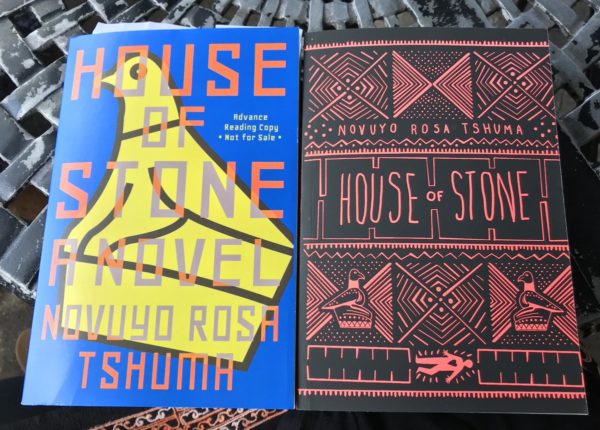

Regardless of where we fall in that debate, bookshelves will soon be teeming with additional contenders. Will Novuyo Rosa Tshuma’s (Shadows) debut novel House of Stone (January 2019, W. W. Norton) satisfy those searching for the Great Zimbabwean Novel? Could Caine Prize–winning author Namwali Serpell’s debut The Old Drift (due later this year from Hogarth Press) really be the Great Zambian Novel we have all been waiting for? What will Ayesha Harruna Attah’s (Harmattan Rain) new novel The Hundred Wells of Salaga (February 2019, Other Press) tell us about pre-colonial Ghanaian history?

In her review of Kenyan writer Peter Kimani’s Dance of the Jakaranda (2017, Akashic Books) for The New York Times, Fiammetta Rocco noted the explosion of African writers exploring historical fiction, work that includes Cameroonian writer Patrice Nganang’s Mount Pleasant (2016, Farrar, Straus and Giroux) and Zambia-born writer Petina Gappah’s (An Elegy for Easterly) retelling of the final journey of David Livingstone, Out of Darkness, Shining Light, which Scribner will put out next summer. Kimani’s novel has an impressive breadth and scope. His illustration of the construction of the railway from Mombasa to the hinterland of Kenya in the early 20th century follows three men — a British colonial administrator, a Christian preacher, and an Indian — whose lives have intersected in unexpected ways.

In conversation with Kimani at Waterstones in London in March, Rocco asked him why so many contemporary writers seemed to be choosing historical fiction, and he answered, “Writers are attempting to resolve or reflect on history,” which is not surprising since much of African history has been written by outsiders. His response echoes that of Makumbi, who when asked during a panel discussion at last year’s Ake Arts and Book Festival how the lack of African history recorded by Africans affects historical fictions said, “History clings to our skin. Somehow we must remember that we remember differently.”

Indeed, Makumbi’s Kintu is notable for not including any British characters or narration detailing the colonial incursion. It focuses purely on Ugandan history, as if the 60 or so years of British presence were insignificant. Owuor’s Dust reflects on a period of Kenyan history during the Moi era (1978–2002) that has been silenced, a time when genocide was being perpetrated against the Luo peoples. And Agaat obliquely tackles the land issue in South Africa through the eyes of a paralyzed white woman with motor neuron disease and her adopted “coloured” servant girl turned brokenhearted caregiver.

These “silenced voices” are unique and bold in their portrayal of subjects usually overlooked by mainstream fiction storytellers and historians. They recenter at the heart of their “histories” long-hidden truths, curses, and mysteries, and then provide resolutions of sorts. In describing Agaat in her New York Times review, Liesl Schillinger wrote,

It’s a monument to what the narrator calls “the compulsion to tell,” expressing truths that are too heartfelt, revelatory and damaging for proud people to speak aloud — or even to admit to themselves in private.

These are personal stories, yes, but with great historical, emotional, and literary significance.

Using the novel as a means of expressing alternative history has long been at the center of postcolonial literary theory, and works that utilize this approach have become a mainstay of the curricula of more progressive world literature courses globally. But it is a form that has not been dominated by female authors, and it has only recently become favored by writers from Africa. While authors such as Lauren Beukes, Nnedi Okorafor, Tomi Adeyemi, and Shadreck Chikoti have been exploring speculative or futuristic African fiction, there is an equal, perhaps weightier movement toward the past that refocuses African fiction on the complexities of the continent’s history. The time appears to have come for in-depth retellings and reclamations of what had previously been controlled by white European writers. As Kimani notes in an interview with Dan Magaziner for the website Africa is a Country,

[H]istorical fiction serves to reclaim a people’s history, or at least inject fresh perspectives to counter the dominant colonial views. In most instances, colonial histories are fraught with inaccuracies, distortions and simple falsifications.

Fred Khumalo, while reflecting on his historical novel about the sinking of the SS Mendi, Dancing the Death Drill (2017, Jacaranda Books), in a recent article for TheJohannesburg Review of Books, states,

There is no reason why, in principle, a novel may not have its basis in research that is as comprehensive as that of a scholarly work of history — indeed, there is no reason why the research may not be more comprehensive, and no reason why, in principle, a novelist’s portrayal of the past may not be truer and more accurate than that produced by a scholarly historian.

Read the full essay HERE.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions