In the midst of the pressure to deliver under that heavy tag “African Writer,” in the back and forth between critics and between writers and between critics and writers, in the midst of big novels and million-dollar book deals and accumulating prizes, it is easy to lose sight of community and what it means to many on the literary scene.

Here are five instances where writers from our continent demonstrated a bounteous spirit of community, five beautiful, humbling acts of generosity. They teach us that social awareness is important, that writing is not a competition, and most all, that there are many ways to make a difference, and that they all matter.

Aminatta Forna, The Rogbonko Project, 2002 till Date

When literary people think of “building community,” they do it in expected ways—founding workshops, founding publishing houses, founding magazines and journals, building mentorship networks. But when Aminatta Forna first thought of it, it was something unconventional. Last December, we ran a special feature with photos to mark the 15th year of the philanthropic initiative she started: The Rogbonko Project, which has driven the rebuilding of a village in Sierra Leone.

When she began it, the initiative’s mission was to build a school in the village, which, as a result of the start of the country’s civil war in 1991, fell behind the rebel line and was cut off from the rest of the country for a decade, and ran into serious economic decline. But since then, the initiative has further run sanitation and maternal health projects. The Rogbonko Project is further interesting as “every project undertaken in Rogbonko is initiated, administered and entirely run by the village.” It is rooted in “the belief that Africans already possess the knowledge, will and systems to transform their living conditions.” The project is modeled to prove that “Africa has all the experts it needs—they’re the people who live there.”

We applaud the truly great, humbling work Aminatta Forna has put in here—“applaud,” because we have no adequate words for this. Aminatta Forna is the ultimate inspiration. The critically acclaimed, Windham-Campbell Prize-winning, extraordinarily busy Sierra Leonean-Scottish author’s fourth novel Happiness came out in March, landing her the cover of Kirkus Reviews.

Please donate to the project HERE.

Visit the project Website HERE.

NoViolet Bulawayo, Etisalat Prize Fellowship, 2014

In April 2014, two months after she received the inaugural Etisalat Prize for Literature for her Man Booker Prize-shortlisted debut novel We Need New Names, the Etisalat Prize announced that NoViolet “has, in a genuine demonstration of sportsmanship, gifted her runner-up, Yewande Omotoso, the Fellowship attached to her winning.” Yewande Omotoso was a finalist for her novel Bom Boy.

The fellowship required four months at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK, under the mentorship of Professor Giles Foden, author of The Last King of Scotland. While she kept the $15,000 (£10,000) prize money, NoViolet’s prior commitment to her then ongoing Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University meant she could not be available for University of East Anglia. “I have gifted it to my runner-up, Yewande Omotoso, in the hope that her participation would further promote the values that Etisalat Nigeria sought to achieve with this literary prize,” said the Zimbabwean novelist known for her easygoing humility.

At that point, We Need New Names had collected the 2014 PEN / Hemingway Award for Debut Fiction a month earlier and the Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction at the Los Angeles Times Book Prizes days before the announcement, on its way to becoming one of the most-awarded debuts by an African. The gesture was widely applauded.

Namwali Serpell, Caine Prize Money, 2015

It was the talk of the scene back in 2015 when, after becoming the first Zambian to win the Caine Prize for her story “The Sack,” Namwali Serpell announced that she would be splitting her £10,000 ($15,000) prize money with her fellow shortlisted writers—South Africans Fatima Kola and Masande Ntashanga, and Nigerians Elnathan John and Segun Afolabi—“as an act of mutiny.” It was a radical first.

“It is very awkward to be placed into this position of competition with other writers that you respect immensely,” she said, because she understood that literary competitions are not about fighting to the death to win a prize but about supporting people you respect. “Having a single winner is for hype rather than interest.”

But this is an example of how a gracious decision can double as a political protest: During the Caine Prize events in London, Serpell had asked why, if the focus was Africa, the events were being held in London. Surely, Lagos or Johannesburg or Nairobi would be better? The reply she got stunned her: “This is where the money is.” And so she decided to show that it isn’t about the money.

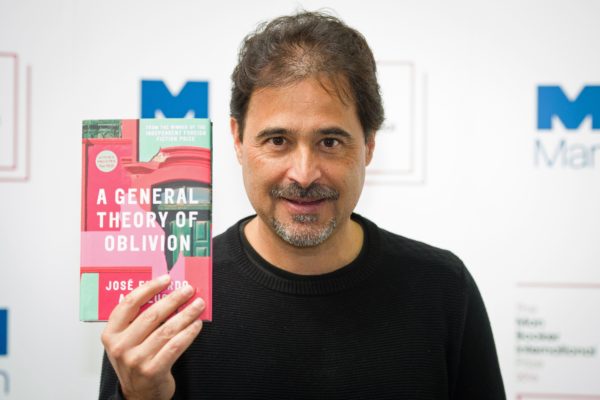

Jose Eduardo Agualusa, Public Library Building, 2017

In June of 2017, celebrated Angolan writer Jose Eduardo Agualusa’s 20th book, A General Theory of Oblivion, made him the second African to win the €100,000 International Dublin Literary Award. The prize money is traditionally shared between the author (€75,000) and his translator (€25,000).

€75,000 is a fat sum, and Agualusa announced he would use it to “fulfil a dream of building a public library” in his adopted home, Mozambique. “What we really need is a public library, because people don’t have access to books, so if I can do something to help that, it will be great,” he said. “We have already found a place and I can put my own personal library in there and open it to the people of the island. It’s been a dream for a long time.”

But Agualusa went further. Due to his friendship with his translator Daniel Hahn, he announced that he will further donate €2,000 to the Translators Association First Translation Prize.

Makena Onjerika, Caine Prize Money, 2018

For all the criticism it gets, which is entirely fair, the Caine Prize is certainly doing one thing right: giving its winners reasons to be generous. This July, after Makena Onjerika won it for her story “Fanta Blackcurrant,” making her the fourth Kenyan to take it home, she stated, in misreported news, that she would be donating “half” of the prize money to “help rehabilitate street children” in Kenya—a demographic from which her story’s protagonist comes.

“Kenyans – me included – do not see street kids as children,” she said. “There are children, and then there are ‘chokora.’” “Chokora,” a derogatory Swahili term, means “street urchins.” As for the rest of the money? “With the rest of the money I’ll buy a car,” she said. “Or maybe a motorcycle to get through traffic jams in Nairobi.”

A day later, however, Onjerika tweeted a clarification: She “will be donating about a tenth of my winnings to a street rehabilation center and hopefully working with others for the long term around children’s affairs.” A tenth, not half. Still, it is affecting. What matters the most is that she is doing it.

Are there more of such examples that we missed?

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions