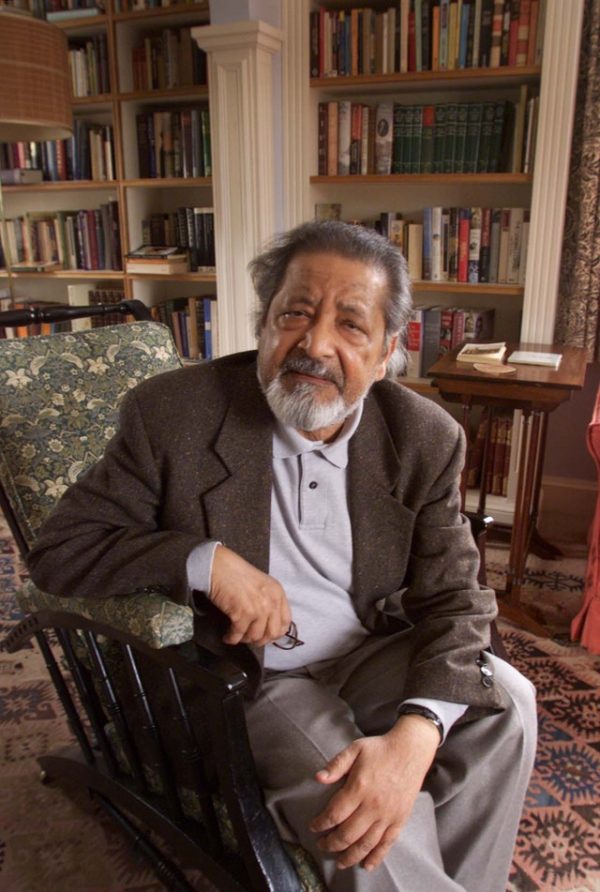

VS Naipaul, Nobel Prize and Booker Prize-winning novelist and nonfiction writer, passed on days ago at 85 years of age. As is the norm, countless think pieces have appeared on his life. While Naipaul’s genius talent and his standing as a literary great aren’t in doubt, it is his legacy that stutters. Born in Trinidad of Indian ancestry, Naipaul moved to the UK to study at Oxford, work for the BBC, and launch one of the most formidable literary careers yet seen, churning out first-rate fiction and nonfiction books with consistency: In a Free State, A House for Mr Biswas, A Bend in the River, The Enigma of Arrival, and more.

But despite coming from a former British colony, he never looked at former colonies with kindness. Kindness, though, wasn’t a quality he was known for, given his quite harsh comments about other writers, and in particular stating that no female writer in history, including and especially Jane Austen, is his equal. Comments and views which over the decades have invited accusations of neocolonialist tendencies and one-dimensional misanthropy and attracted the ire of such figures as Derek Walcott, Salman Rushdie, and Edward Said. The man, though, seemed unbothered, and even stated that reading what has been said about him amused him, going further to state: “If a writer doesn’t generate hostility, he is dead.”

We bring you what some of Africa’s leading literary figures—Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Aminatta Forna, Binyavanga Wainaina, Teju Cole, and Namwali Serpell—thought about a man who said, of his time in Uganda, that “Africans need to be kicked, that’s the only thing they understand,” and whose answer to the question “What is the future in Africa?” was: “Africa has no future.” Here we have included only what was said in public while he was still alive.

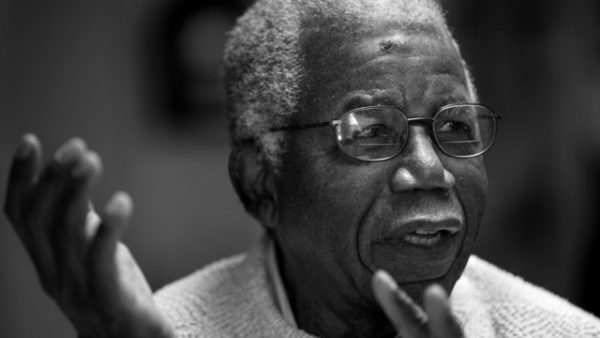

Chinua Achebe: “A brilliant writer who sold himself to the West”

In 1985, ten years after his seminal criticism of Joseph Conrad’s racism, Chinua Achebe said this about VS Naipaul:

“I do admire Mr. Naipaul, but I am rather sorry for him. He is too distant from a viable moral centre; he withholds his humanity; he seems to place himself under a self-denying ordinance, as it were, suppressing his genuine compassion for humanity. His style is all too perfect, steel-bright, metallic, and so forth.”

Then came the coup de grace: Naipaul, Achebe said, “is the case of a brilliant writer who sold himself to the West.”

In his collection of essays Home and Exile, Chinua Achebe describes select parts of Naipaul’s work as “downright outrageous” and “pompous rubbish.”

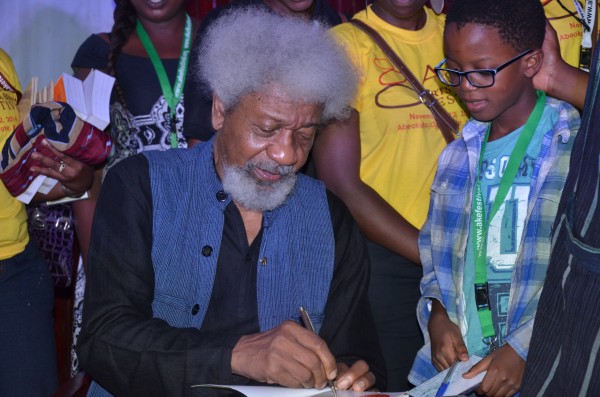

Wole Soyinka

VS Naipaul took the sole shot when, after Wole Soyinka was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986, he said, according to Paul Theroux: “Has he written anything?” Soyinka, he said, was “a marvellously establishment figure, actually,” and the Swedish Academy was “pissing on literature from a great height.” It wasn’t the first or only time he went that low: he’d called Henry James “the worst writer in the world.”

In 2001, though, fifteen years after Soyinka did, Naipaul would receive the Nobel Prize, and Soyinka, as far as we know, never replied in public.

Trivia: In a 1982 review of Soyinka’s Ake: The Years of Childhood, John Leonard writes this:

“What if V.S. Naipaul were a happy man? What if V.S. Pritchett had loved his parents? What if Vladimir Nabokov had grown up in a small town in western Nigeria and decided that politics were not unworthy of him? I do not take, or drop, these names in vain. Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian novelist, playwright, critic and professor of comparative literature, belongs in their company.”

Binyavanga Wainaina: “In the rush to fulfill his stated and sometimes templated mission, he failed to notice many seismic things”

In a 2009 interview with Pambuzuka, Binyavanga lists Naipaul’s A Way in the World among his favourite five books, alongside Kojo Laing’s Search Sweet Country, Bruno Shultz’s The Street of Crocodiles, Ahmadou Kouruma’s Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote, and Mongo Beti’s Mission To Kala.

In a Boston Globe review of Naipaul’s 2010 nonfiction book The Masque of Africa, in which Naipaul journeys from Uganda to Nigeria to Gabon via the Ivory Coast and Ghana, and to South Africa, Binyavanga writes:

In “The Masque of Africa,’’ Naipaul uses himself as a character only as a way for us to see others through his conflicts, moods, ears, eyes, and biases. And in between his scenes of sharply observed interactions, we are always surrounded by the people of the continent talking, as he chitchats his way from country to country. It is the best aspect of this book, and it gives us a lot of room to come to a different conclusion than his.

Then he adds:

For this is not a fully accomplished book. It stutters and finds no solid ground. Naipaul’s vision has always had an intelligence and instinct for central dramas of our times. His nonfiction books have always shaken with meaning and aroused great passions.

On Naipaul’s stay in Gabon, Binyavanga writes:

It is also in Gabon that the book tumbles and falls. When I first read this chapter, titled “Children of the Old Forest,’’ I found my mind wandering into the world of the movie “Avatar’’ with its holy trees, hallucinatory plants, astral journeys, drums, witch doctors, and mysterious and powerful “energies.’’

The problem is not in the depiction of the existence of these things, which is precious and true; it is here that I stop trusting Naipaul’s curiosity, his ability to find big questions to ask. In the rush to fulfill his stated and sometimes templated mission, he failed to notice many seismic things. This new world has learned to transport oral cultures in digital ways. Old cultures are reorganizing and thriving, and this is causing all kinds of upheaval.

Aminatta Forna: “A difficult, imperfect narrator…but he is an honest one…Somehow…I had grown to like him”

In her The Guardian review of Naipaul’s The Masque of Africa, Aminatta Forna wrote the following:

They can be playful, something more literal minded western writers often fail to grasp, for when it comes to Africa humour is the first casualty. Naipaul gets it. He is dry, often irked, sometimes enraged. He is quite rude. But he is also patient (not a trait often associated with him), engaged, funny, self-reflective and thoughtful.

He finds Africa a struggle. Journeys are almost always longer than he is told; he is kept waiting; diviners all demand to be paid; there is rubbish everywhere; the temperatures are intolerable.

By Gabon, he has recovered some of his equilibrium, and it is here, in the forests, that he finds something akin to Africa’s true spirituality.

Where Naipaul does both Africa and himself a disservice is in failing to verify much of his information. Somehow, when it comes to Africa, rigour flies out of the window. Naipaul talks of rituals performed using human body parts. Neither Naipaul nor we know if any of this is true. I would treat it with scepticism, as sorcerers famously like to big themselves up by creating a culture of fear. If locals are turning to magic (which they may well be), it is perhaps because such beliefs the world over are the last resort of the poor, the disenfranchised and the dispossessed – in short, those with no other way to change their lives. It is only in South Africa, where the legacy of apartheid proves enduring and unavoidable, and where the sangoma’s hollow promises find ever more seekers willing to believe, that Naipaul comes close to this understanding.

In another section of the book, he takes at face value a story about the ritual killing of hundreds of people for the funeral of President Houphouët-Boigny. The source is “foreign (but well-placed)”.

…Such people exploit the eagerness of outsiders to believe Africans are capable of the very worst.

The Masque of Africa is a book for outsiders, for those who may never visit Africa or may know it only superficially. But it is also a book in which Africans themselves may find something to learn. Naipaul is a difficult, imperfect narrator who does not care to be liked, but he is an honest one and doesn’t dissemble. Somehow, by the end of it all, and despite his best efforts, I had grown to like him.

Namwali Serpell: “His commendable – and exquisitely wrought – attention to animal suffering seems to supersede his concern for people”

In her own brief SFGate review of Naipaul’s The Masque of Africa, Namwali Serpell notes that Naipaul “tends to use the words ‘simple’ and ‘strange’ as vague euphemisms for his unease with African cultural practices and forms of knowledge,” and that “there is a constant tension between his subject matter and his haplessly Western frame of reference. Looking at Africa, Naipaul sees Shakespeare, Conrad, even Shelley.” His vision is “warped” and “comes to seem myopic.”

She continues:

Nor do his efforts to qualify his prejudices soften them. It is vexing that his commendable – and exquisitely wrought – attention to animal suffering seems to supersede his concern for people.

Only in South Africa, where he cannot pretend to ignore race or its history, does Naipaul’s lens refract complexity, particularly in his account of Gandhi’s years there. For the most part, he chooses to set aside “the relativity of perceptions, too much of a quicksand for the short-term traveler to go into.” But the book’s form does oscillate – “you swung from one Africa to another” – between the conflicted and conflicting voices of the Africans he meets and Naipaul’s own.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: “I started reading his book…and I just stopped halfway and thought—this is really bad”

Part of the advance press for Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2013 novel Americanah centered on how she stepped into the arena of writerly disses by taking on VS Naipaul, in both the novel via Ifemelu and in a comment afterwards. In a hair salon scene in Americanah, after a white female character says that Naipaul’s 1979 novel A Bend in the River is “the most honest book I’ve read about Africa,” Ifemelu “made a sound, halfway between a snort and nothing,” before proceeding:

“She did not think the novel was about Africa at all. It was about Europe, or the longing for Europe, about the battered self-image of an Indian man born in Africa, who felt so wounded, so diminished, by not having been born European.”

This passage, writes New York Daily News, “speaks with the requisite veiled clarity of the literary insult.” In a subsequent comment to the London Evening Standard, Adichie made it overt: “I’ve become very tired of this nonsense where he’s supposed to be the best writer in the world. God bless him, I wish him well, but I think that just because you’re an old man who’s nasty doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t actually take your work apart.”

Asked about it in a 2014 interview with Livemint, Adichie said:

It was just annoyance. Somebody had said to me that A Bend in the River was the African novel, and I was just irritated by that. It was not about Naipaul personally, I have read his interviews and instead of feeling angry, I just feel sorry because I think, How did this happen?

Then the interviewer asked how she rated him as a writer:

I liked the first book (The Mystic Masseur). I also really liked The Mimic Men. But the other things I have read…. I think that if you are from a certain part of the world, i.e. the developing part, and you say that my people are monkeys, then you become celebrated and suddenly your book is the book that explains everything. I think that is just nonsense. The idea that A Bend in the River explains Africa is just nonsense. It doesn’t. I think most of the reading of that book as some grand narrative is because of the personality of Naipaul. I think if he didn’t represent this “media” kind of self, a Western worshipping in a blind kind of way, this would have never happened.

Many writers from other parts of the world are aware of how messed up our countries are, but that is not the only thing we know about our countries. But with him, it is a kind of singular vision. Recently, I started reading his book about Africa (A Congo Diary) and I just stopped halfway and thought—this is really bad. It is also inaccurate.

Before that, in her own 2006 Booker Prize-winning The Inheritance of Loss, Adichie’s friend, Kiran Desai, had also taken a shot at Naipaul as two characters discuss A Bend in the River: “Oh, I don’t know… I think he’s strange. Stuck in the past… He has not progressed. Colonial neurosis, he’s never freed himself from it.”

Teju Cole: “Your work has meant so much to an entire generation. [But] I don’t agree with all your views”

Teju Cole is quite the admirer of VS Naipaul’s talents. In his 2016 collection of essays, Known and Strange Things, he has two essays: one on meeting him, the other on his novel A House for Mr Biswas. Cole’s essay on meeting him, “Natives on a Boat,” was widely read when it first appeared in The New Yorker in 2012. In it, he writes about Naipaul telling him to write about Amos Tutuola:

“Have you written about Tutuola?” I said, no, I hadn’t. “It would be interesting,” he said. I demurred, and said I found the work odd, minor. There was something in Tutuola’s ghosts and forests and unidiomatic English that confirmed the prejudices of a European audience. “That’s what would be interesting about it,” he said. “A reconsideration. You would be able to say something about it, something of value.”

And about being influenced by Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival:

But it was “The Enigma of Arrival,” tirelessly intense, its intelligence fastened to the world of humans and of nature, that most influenced my own work, my own ear. I adore, still, its language, its inner music.

And his own toast to Naipaul:

When three or four others had spoken, I gathered up my courage and said: “Vidia, I would like to join the others in celebrating your work”—though, in truth, the new book, called “The Masque of Africa,” ostensibly a study of African religion, was oddly narrow and stilted, not as good as his other voyages of inquiry, though still full of beautiful observation and language; but there is a time for literary criticism, and a time for toasts. I went on: “Your work which has meant so much to an entire generation of post-colonial writers. I don’t agree with all your views, and in fact there are many of them I strongly disagree with,”—I said “strongly” with what I hoped was a menacing tone—“but from you I have learned how to be productively disagreeable in my own views. I and others have learned, from you, that it is fine to be independent, that it is fine to go your own way and go against the crowd. You went your own way no matter what it cost you. Thank you for that.” I raised my glass, and everyone else raised theirs. A silence fell and Vidia looked sober, almost chastened. But it was a soft look. “Thank you,” he said. “I’m very moved. I’m very moved.”

About Naipaul telling him to write about their meeting:

The party was ending. I said, “This was not what I expected.” “Oh?” he said, some new mischief in his eyes, “And what did you expect?” “I don’t know. Not this. I thought you’d be surly, and that I’d be rude.” He was pleased. “Very good, very good. So you must write about this. You must write it down, so that others know. That would be good for you, too.” The combination of ego, tenderness, and sly provocation was typical.

And then this:

Finally, after about twenty minutes, Nadira came for her husband. The hand lifted itself from its resting place on my knee. This benevolent old rheumy-eyed soul: so fond of the word “nigger,” so aggressive in his lack of sympathy towards Africa, so brutal in his treatment of women. He knew nothing about that. He knew only that he needed help standing up, needed help walking across the grand marble-floored foyer towards the private elevator.

On A House for Mr Biswas, Cole writes in The Guardian:

Great in macrocosm, the novel is also flawless in microcosm. It contains many perfect set pieces, strewn like jewels through the book, in which the prose gleams with a kind of secret knowledge. Many are the moments of imaginative sympathy that continue to bloom in the mind long after the page is turned. One such account, of the burning of poui sticks for the rough village sport of stick-fighting, captures the way the scent of the sticks opens up in Mr Biswas a sudden seam of memory.

In an earlier listicle for The Guardian also, Cole had listed The Enigma of Arrival among his “Top 10 Novels of Solitude.”

What do you think of the reactions? Sound off in the comments section.

Cassandra August 24, 2018 17:04

Folks don't need to reside with violence.