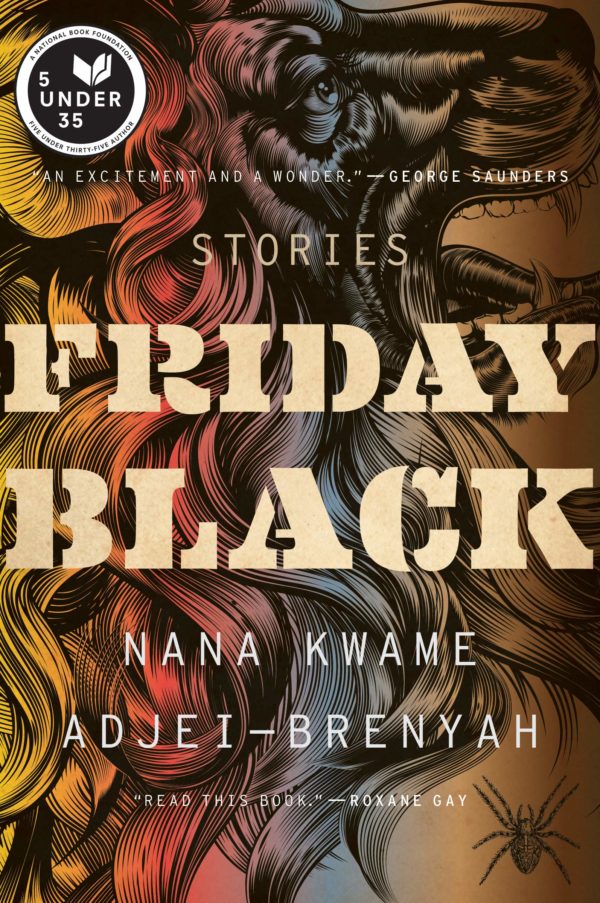

If you’ve ever hankered for fresh, new writing, here is a book you should have on your #TBR list. Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah is a star in the making, and his debut book, which was officially published yesterday, is getting the attention of critics.

The collection of 12 short stories is titled Friday Black. He mixes satire with fantasy to create what is being hailed as a powerful commentary on consumer culture and racism.

Adjei-Brenyah was born to Ghanaian parents. He grew up in Spring Valley, N.Y., where, as a little boy he read a lot of science fiction and fantasy and Japanese Manga. He received an undergraduate degree from the University at Albany, SUNY and went on to pursue an M.F.A in creative writing at Syracuse University where he studied with novelist Lynne Tillman and short story master George Saunders.

Adjei-Brenyah’s work is defined by a distinctively open approach to genre. His work flits between fantasy, satire, genre fiction, and realism.

In the New York Times review of Friday Black, Tommy Orange is impressed by the way Adjei-Brenyah uses futuristic elements to interrogate contemporary questions about race, power, consumer culture, and violence. Orange concludes that Friday Black is “a powerful and important and strange and beautiful collection of stories meant to be read right now.”

Enjoy this teaser from the short story titled “Friday Black.”

Fela, the headless girl, walked toward Emmanuel. Her neck jagged with red savagery. She was silent, but he could feel her waiting for him to do something, anything.Then his phone rang, and he woke up.

He took a deep breath and set the Blackness in his voice down to a 1.5 on a 10-point scale. “Hi there, how are you doing today? Yes, yes, I did recently inquire about the status of my application. Well, all right, okay. Great to hear. I’ll be there. Have a spectacular day.” Emmanuel rolled out of bed and brushed his teeth. The house was quiet. His parents had already left for work.

That morning, like every morning, the first decision he made regarded his Blackness. His skin was a deep, constant brown. In public, when people could actually see him, it was impossible to get his Blackness down to anywhere near a 1.5. If he wore a tie, wing-tipped shoes, smiled constantly, used his indoor voice, and kept his hands strapped and calm at his sides, he could get his Blackness as low as 4.0.

Though Emmanuel was happy about scoring the interview, he also felt guilty about feeling happy about anything. Most people he knew were still mourning the Finkelstein verdict: after twenty-eight minutes of deliberation, a jury of his peers had acquitted George Wilson Dunn of any wrongdoing whatsoever. He had been indicted for allegedly using a chain saw to hack off the heads of five black children outside the Finkelstein Library in Valley Ridge, South Carolina. The court had ruled that because the children were basically loitering and not actually inside the library reading, as one might expect of productive members of society, it was reasonable that Dunn had felt threatened by these five black young people and, thus, he was well within his rights when he protected himself, his library-loaned DVDs, and his children by going into the back of his Ford F-150 and retrieving his Hawtech PRO eighteen-inch 48cc chain saw.

The case had seized the country by the ear and heart, and was still, mostly, the only thing anyone was talking about. Finkelstein became the news cycle. On one side of the broadcast world, anchors openly wept for the children, who were saints in their eyes; on the opposite side were personalities like Brent Kogan, the ever gruff and opinionated host of What’s the Big Deal?, who had said during an online panel discussion, “Yes, yes, they were kids, but also, fuck niggers.” Most news outlets fell somewhere in-between.

On verdict day, Emmanuel’s family and friends of many different races and backgrounds had gathered together and watched a television tuned to a station that had sympathized with the children, who were popularly known as the Finkelstein Five. Pizza and drinks were served. When the ruling was announced, Emmanuel felt a clicking and grinding in his chest. It burned. His mother, known to be one of the liveliest and happiest women in the neighborhood, threw a plastic cup filled with Coke across the room. When the plastic fell and the soda splattered, the people stared at Emmanuel’s mother. Seeing Mrs. Gyan that way meant it was real: they’d lost. Emmanuel’s father walked away from the group wiping his eyes, and Emmanuel felt the grinding in his chest settle to a cold nothingness. On the ride home, his father cursed. His mother punched honks out of the steering wheel. Emmanuel breathed in and watched his hands appear, then disappear, then appear, then disappear as they rode past streetlights. He let the nothing he was feeling wash over him in one cold wave after another.

But now that he’d been called in for an interview with Stich’s, a store self-described as an “innovator with a classic sensibility” that specialized in vintage sweaters, Emmanuel had something to think about besides the bodies of those kids, severed at the neck, growing damp in thick, pulsing, shooting blood. Instead, he thought about what to wear.

In a vague move of solidarity, Emmanuel climbed into the loose-fitting cargoes he’d worn on a camping trip. Then he stepped into his patent-leather Space Jams with the laces still clean and taut as they weaved up all across the black tongue. Next, he pulled out a long-ago abandoned black hoodie and dove into its tunnel. As a final act of solidarity, Emmanuel put on a gray snapback cap, a hat similar to the ones two of the Finkelstein Five had been wearing the day they were murdered—a fact George Wilson Dunn’s defense had stressed throughout the proceedings.

Emmanuel stepped outside into the world, his Blackness at a solid 7.6. He felt like Evel Knievel at the top of a ramp.

From npr.org

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions