BLEACH

I bet you didn’t know that bleach masks the smell of blood. Most people use bleach indiscriminately, assuming it is a catchall product, never taking the time to read the list of ingredients on the back, never taking the time to return to the recently wiped surface to take a closer look. Bleach will disinfect, but it’s not great for cleaning residue, so I use it only after I have first scrubbed the bathroom of all traces of life, and death.

It is clear that the room we are in has been remodelled recently. It has that never-been-used look, especially now that I’ve spent close to three hours cleaning up. The hardest part was getting to the blood that had seeped in between the shower and the caulking. It’s an easy part to forget.

There’s nothing placed on any of the surfaces; his shower gel, toothbrush and toothpaste are all stored in the cabinet above the sink. Then there’s the shower mat—a black smiley face on a yellow rectangle in an otherwise white room.

Ayoola is perched on the toilet seat, her knees raised, and her arms wrapped around them. The blood on her dress has dried and there is no risk that it will drip on the white, now glossy floors. Her dreadlocks are piled atop her head, so they don’t sweep the ground. She keeps looking up at me with her big brown eyes, afraid that I am angry, that I will soon get off my hands and knees to lecture her.

I am not angry. If I am anything, I am tired. The sweat from my brow drips onto the floor and I use the blue sponge to wipe it away.

I was about to eat when she called me. I had laid everything out on the tray in preparation—the fork was to the left of the plate, the knife to the right. I folded the napkin into the shape of a crown and placed it at the centre of the plate. The movie was paused at the beginning credits and the oven timer had just rung, when my phone began to vibrate violently on my table.

By the time I get home, the food will be cold.

I stand up and rinse the gloves in the sink, but I don’t remove them. Ayoola is looking at my reflection in the mirror.

“We need to move the body,” I tell her.

“Are you angry at me?”

Perhaps a normal person would be angry, but what I feel now is a pressing need to dispose of the body. When I got here, we carried him to the boot of my car, so that I was free to scrub and mop without having to countenance his cold stare.

“Get your bag,” I reply.

We return to the car and he is still in the boot, waiting for us.

The third mainland bridge gets little to no traffic at this time of night, and since there are no lamplights, it’s almost pitch black, but if you look beyond the bridge you can see the lights of the city. We take him to where we took the last one—over the bridge and into the water. At least he won’t be lonely.

Some of the blood has seeped into the lining of the boot. Ayoola offers to clean it, out of guilt, but I take my homemade mixture of one spoon of ammonia to two cups of water from her and pour it over the stain. I don’t know whether or not they have the tech for a thorough crime scene investigation in Lagos, but Ayoola could never clean up as efficiently as I can.

THE NOTEBOOK

“Who was he?”

“Femi.”

I scribble the name down. We are in my bedroom. Ayoola is sitting cross-legged on my sofa, her head resting on the back of the cushion. While she took a bath, I set the dress she had been wearing on fire. Now she wears a rose-coloured T-shirt and smells of baby powder.

“And his surname?”

She frowns, pressing her lips together, and then she shakes her head, as though trying to shake the name back into the forefront of her brain. It doesn’t come. She shrugs. I should have taken his wallet.

I close the notebook. It is small, smaller than the palm of my hand. I watched a TEDx video once where the man said that carrying around a notebook and penning one happy moment each day had changed his life. That is why I bought the notebook. On the first page, I wrote, I saw a white owl through my bedroom window. The notebook has been mostly empty since.

“It’s not my fault, you know.” But I don’t know. I don’t know what she is referring to. Does she mean the inability to recall his surname? Or his death?

“Tell me what happened.”

THE POEM

Femi wrote her a poem.

(She can remember the poem, but she cannot remember his last name.)

I dare you to find a flaw

in her beauty;

or to bring forth a woman

who can stand beside

her without wilting.

And he gave it to her written on a piece of paper, folded twice, reminiscent of our secondary school days, when kids would pass love notes to one another in the back row of classrooms. She was moved by all this (but then Ayoola is always moved by the worship of her merits) and so she agreed to be his woman.

On their one-month anniversary, she stabbed him in the bathroom of his apartment. She didn’t mean to, of course. He was angry, screaming at her, his onion-stained breath hot against her face.

(But why was she carrying the knife?)

The knife was for her protection. You never knew with men, they wanted what they wanted when they wanted it. She didn’t mean to kill him, she wanted to warn him off, but he wasn’t scared of her weapon. He was over six feet tall and she must have looked like a doll to him, with her small frame, long eyelashes and rosy, full lips.

(Her description, not mine.)

She killed him on the first strike, a jab straight to the heart. But then she stabbed him twice more to be sure. He sank to the floor. She could hear her own breathing and nothing else.

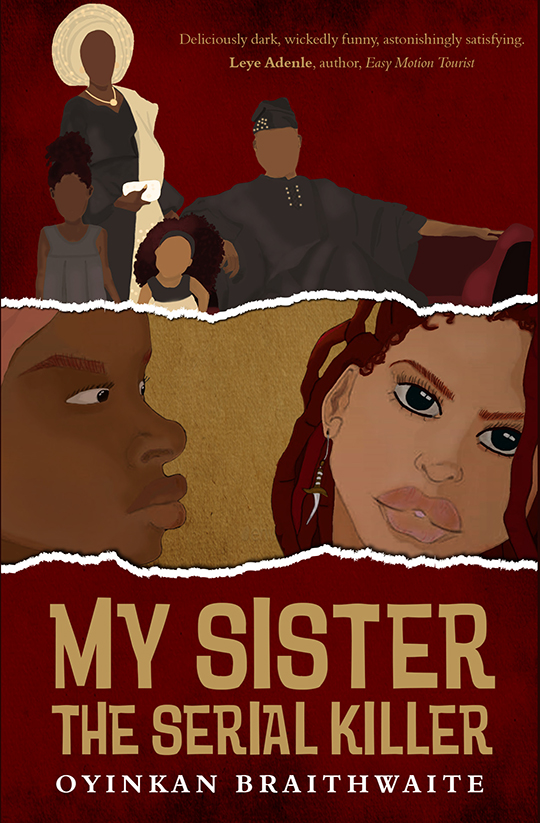

Preorder My Sister, The Serial Killer |

**********

About the Author:

Oyinkan Braithwaite is a graduate of Creative Writing and Law from Kingston University. Following her degree, she worked as an assistant editor at Kachifo, a Lagos-based publishing house, and has been freelancing as a writer and editor since. In 2014, she was shortlisted as a top-ten spoken-word artist in the Eko Poetry Slam, and in 2016 she was a finalist for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. She lives in Lagos, Nigeria.

Oyinkan Braithwaite is a graduate of Creative Writing and Law from Kingston University. Following her degree, she worked as an assistant editor at Kachifo, a Lagos-based publishing house, and has been freelancing as a writer and editor since. In 2014, she was shortlisted as a top-ten spoken-word artist in the Eko Poetry Slam, and in 2016 she was a finalist for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. She lives in Lagos, Nigeria.

The Best Debut Books of February 19, 2019 18:14

[…] READ A STORY FROM SMITH’S DEBUT BOOK, RUTTING SEASON, FOR GUERNICA […]