“African science fiction is not rising. It is here,” writes Tade Thompson in a defiant but illuminating piece about that genre of writing called African Science Fiction and Fantasy. Thompson is a proud leader of the pack of writers of African descent, or who live in the continent, who write identity-bending, mind-bending experimental stuff far from the beaten—some would say tired—narrative that drowns African fiction like too much sauce on white rice.

Here is a good list of African SFF books.

Thompson might bristle at this, but African SFF is undergoing a renaissance with several star writers dominating the landscape. Some of this is thanks to the dogged work of the Zimbabwean writer Ivor W. Hartmann who has, over the past decade or more, been editing and producing works of a generation of young writers of the genre. I have followed Hartmann’s works for a long time (here and here); I am a fan of his, although I must admit I am old school, preferring stories that are deeply organic to my lived Nigerian experience. It has been my observation that a lot of what passes for African SFF is unalloyed mimicry of Western fare, with African names and terms thrown in to give it a toga of (African) authenticity. I go back to Amos Tutuola and Ben Okri writing with malarial feverishness about their own flights of fancy, pulling it off with spectacular success. But then it is about identity: we should really be talking about science fiction and fantasy written by writers who happen to be African. And many of them, like Thompson, write damn good science fiction based on vivid imagination drawn from their lived experience.

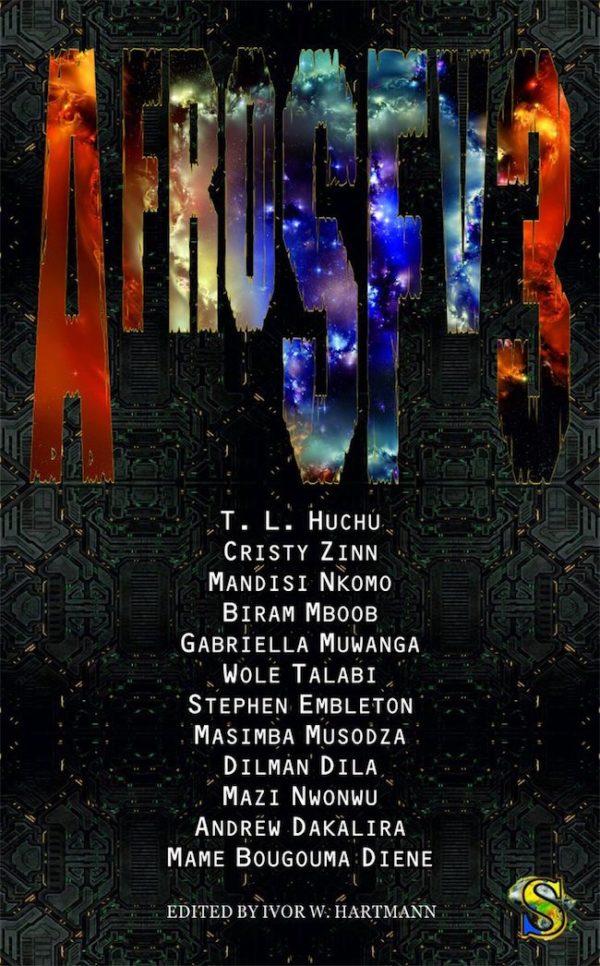

AfroSF v3, the third installment of these works edited by Hartman, is focused on stories around a specific theme—space travel. I enjoyed reading many of the stories, which is quite an achievement for me in the age of social media and clickbait. I heartily recommend this latest volume of stories. There is plenty to enjoy for everyone. This volume pushes the envelope further into the stratosphere and forces the reader to reflect on these questions of identity and the authenticity of stories. This volume is an interesting mix of thinking, although several of the writers stick to familiar themes—of space ships, Mars and other planets, known and unknown. Some of the stories read like scripts that would make great (or even mediocre) movies in the mold of Black Panther or Star Trek. The result is mixed, but many of the stories are successful at it; they redefine with confidence and muscle the notion of space, boundaries and memory, and the result is a book worth the read.

Twelve stories make up this volume. Tendai Huchu’s “Njuzu” is one of my favorites, featuring crisp beautiful prose and vivid imagination. “Njuzu” alone is worth the prize of this uneven volume. It is about space and much more; it explores gender roles and sexuality in refreshing ways even as Huchu paints beautiful images of restless societies on the move. Cristy Zinn’s “The Girl Who Stared at Mars” brims with promise (I like the subtle interrogation of race issues) but soon veers off course into a meandering soliloquy on personal, troubling issues. Still, her take on space exploration is unique and creative, one is reminded that even here on earth there are so many unexplored spaces:

Once, I spent the Christmas holidays with a friend at her parents’ beach house in the Transkei. Like only white people could then, they’d amassed themselves a little paradise where they could stroll down a grassy hill and be on the beach in seconds. We lived on the beach that summer, and once, even though I’m not that enthusiastic about the sea, we went diving. I remember sticking my head under the surface, staring through goggles, and seeing where the water turned murky and went on forever. I had this sudden panic attack thinking how big that sea was. It was a giant expanse and I was small and powerless in it. And yet, I didn’t want to leave. I wanted to know what was beyond where I could see. Space feels like that to me sometimes. I think that’s why I chose my small garden for my sim.

Gabriella Muwanga’s “The Far Side“ is by far my favorite story—engaging, well-researched and with exquisite pacing. What is it about? Go and buy the book, my friend! Stephen Embleton’s “Journal of a DNA Pirate” comes across as part short story and part movie script, but he pulls it off nicely. It is the liveliest and most engaging of the stories, a breathtaking narrative. Embleton is a brilliant mind on steroids. He defines and redefines the concepts of space and memory. The defiant insistence on writing his story on his own terms makes the reader envious.

Dilman Dila’s “Safari Nyota: A Prologue,” about a journey to a planet called Ensi, is full of his patented swag. Dila can write, and this short piece shows why he is the recipient of several awards. Wole Talabi’s “Drift-Flux” would make a good script for a sci fi movie—wait, it is a good script for a sci fi movie. I loved the story; it has depth, written by an engineer who knows what he is talking about. Unfortunately, the wooden clinical prose almost reminds the reader of an engineer’s dry memo. A good story, nonetheless.

It is not a perfect book, of course not. Mandisi Nkomo’s “The EMO Hunter” is yet another opportunity to process social anxieties, but it feels dated in some parts in this age of culture-defying social media and Uber (Just curious: How many millennials still hail taxis? What are those?). Biram Mboob’s “The Luminal Frontier” expertly drowns itself in syrupy vats of orthodoxy, a too-long redux of Star Trek and Black Panther and not in a good way. Mame Bougouma Diene’s “Ogotemmeli’s Song” is a disappointment; it doesn’t even try to be original or engaging, this poor Eurocentric adaptation of what the reader already knows. Mame has watched too many episodes of Star Trek. Similarly, Andrew Dakalira’s “Inhabitable” seems inspired by orthodoxy, writing like someone overdosed on Western sci fi. Finally, I am not sure why Mazi Nwonwu’s “Parental Control” made it to this volume. It is a traditional short story that seems hurriedly tweaked to give the wrong impression that it is sci-fi. It is not. Nwonwu should delete all the pretensions and return the piece to the good story it was.

As the Caine Prize for African Writing lurches from chic irrelevance to chic irrelevance, as it bestows awards on those intent on hawking poverty porn for fame and fortune, it is appropriate to salute the industry of these writers who push the boundaries of thought and imagination to rigorous heights. I propose that, for their next edition, the Caine Prize should simply pick a winner from this collection. There are several winners here and you will not hear me whine about the glorification of poverty porn. Still, I would love to see bolder experimentation by African Science Fiction and Fantasy writers that is organic to African spaces, that blows up boundaries and makes compelling reading. Nwonwu alludes to this in his reference to Nigeria’s late great Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, the leading coup plotter in the events of January 1966 who died under mysterious circumstances in 1967. I should write a short piece about this great tree in my village where all the men and women retired to at night and traveled to space only to return at dawn to regale the uninitiated with tales of strange places and people. They traveled to these places via Bluetooth. In the sixties. You don’t believe me? Now we are talking!

About the Reviewer:

Ikhide R. Ikheloa, or Pa Ikhide, is a social critic who writes non-stop on various online media. He was a columnist with Next Newspaper and the Daily Times, Nigeria, where he held forth and offered unsolicited opinions on any and everything to do with literature and the world. He has been published in books, journals and online magazines, and he predicts: “The book and the library are dying. Ideas live.” Find him on twitter @ikhide.

Strange Horizons - On Worldcons and Passport Privilege: An Interview with Rafeeat Aliyu By Gautam Bhatia, By Rafeeat Aliyu May 25, 2020 19:53

[…] Writers series, I learnt about the existence of the Omenana magazine, the Ake Festival, the AfroSF series, and so much more. It's very clear that both the cultural and the infrastructural resources are […]