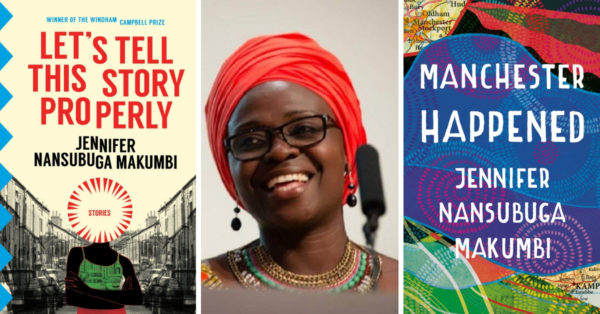

Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s new book, a short story collection, is here. Published in the UK this May by Oneworld as Manchester Happened, and forthcoming in the US in July from Transit as Let’s Tell This Story Properly, the collection is an anticipated one, especially coming after her 2018 Windham-Campbell Prize win.

Here is a description on Amazon:

How far does one have to travel to find home elsewhere? The stories in Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s collection attempt to measure that distance. Centered around the lives of Ugandans in Britain, Let’s Tell This Story Properly features characters both hyper-visible and unseen―they take on jobs at airport security, care for the elderly, and work in hospitals, while remaining excluded from white, British life. As they try to find their place, they drift from a home that feels further and further away. In an ambitious collection by the critically acclaimed author of Kintu, Let’s Tell This Story Properly explores what happens to those who leave.

One of the stories, “Lets Tell This Story Properly,” won her the 2014 Commonwealth Short Story Prize and appeared in Granta. Another, “She Is Our Stupid,” recently appeared on Literary Hub. Here is an excerpt.

_________________________________________________________

My sister Biira is not; she’s my cousin. Ehuu!

Ever heard of King Midas’s barber, who saw the king’s donkey ears and carried the secret until it became too much to bear? I could not hold it in any longer. I stumbled across it five years ago at Biira’s wedding and I have been carrying it since. But unlike Midas’s barber—stupid sod dug a hole in the earth, whispered the secret in there and buried it—my family does not read fiction. A bush grew over the barber’s words and every time the wind blew the bush whispered, King Midas has donkey ears. I have also changed the names. Of course, the barber was put to death. But for me, if this story gets back to my family, death will be too kind.

Back in 1961, Aunty Flower went to Britain on a sikaala to become a teacher—sikaala was scholarship or sikaalasip. Her name was Nnakimuli then. At the time, Ugandan scholars to Britain could not wait to come home, but not Aunty Flower; she did not write either. Instead, she translated Nnakimuli into Flower and was not heard from until 1972.

It was evening when a special hire from the airport parked in my grandfather’s courtyard. Who jumped out of the car? Nnakimuli. As if she had left that morning for the city. They did not recognise her because she was so skinny a rod is fat. And she moved like a rod too. Then the hair. It was so big you thought she carried a mugugu on her head. And the make-up? Loud. But you know parents, a child can do things to herself but a parent will not be deceived. It was Grandfather who said, ‘Isn’t this Nnakimuli?’

Family did not know whether to unlock their happiness because when her father reached to hug her, Nnakimuli planted kisses—on his right cheek and on his left—and her father did not know what to do. The rest of the family held onto their happiness and waited for her to guide them on how to be happy to see her. When she spoke English to them, they apologised: Had we known you were coming we would have bought a kilo of meat…haa, dry tea? Someone run to the shop and get a quarter of sugar…Remember to get milk from the mulaalo in the morning…Maybe you should sit up on a chair with Father; the ground is hard…The bedroom is in the dark…Will you manage our outside bathroom and toilet…Let’s warm your bathwater—you won’t manage our cold water. And when Nnakimuli said her name was Flower, the disconnect was complete. Their rural tongues called her Fulawa. When she helped them, Fl, Fl, Flo-w-e-r, they said Fluew-eh. Nonetheless, she had brought a little something for everyone. People whispered There’s a little of Nnakimuli left in this Fulawa.

Not Fulawa, maalo, it’s Fl, Fl, Flueweh, and they collapsed in giggles.

The following morning, Flower woke up at five, chose a hoe and waited to go digging. She scoffed when family woke up at 6 a.m. Now she spoke Luganda like she never left. Still, family fussed over her bare feet, chewing their tongues speaking English: ‘You’ll knock your toes, you’re not used.’ But she said, ‘Forget Flower; I am Nnakimuli.’

She followed them to the garden where they were going to dig. When they divided up the part that needed weeding, they put her at the end in case she failed to complete her portion. She finished first and started harvesting the day’s food, collected firewood, tied her bunch and carried it on her head back home. She then fetched water from the well until the barrel in the kitchen was full. She even joined in peeling matooke. When the chores were done, she bathed and changed clothes. She asked Yeeko, her youngest sister, to walk her through the village greeting residents, asking about the departed, who got married—How many children do you have?—and the residents marvelled at how Nnakimuli had not changed. However, they whispered to her family Feed her; put some flesh on those bones before she goes back. Nnakimuli combed the village, remembering, eating wild fruit, catching up on gossip. For seven days, she carried on as if she was back for good and family relaxed. Then on the eighth day, after the chores, she got dressed, gave away her clothes and money to her father. She knelt down and said goodbye to him.

‘Which goodbye?’ The old man was alarmed. ‘We’re getting used to you: where are you going?’

_______________________________________________________

Continue reading on Literary Hub.

Ssebunya Micheal November 12, 2021 02:22

Interesting