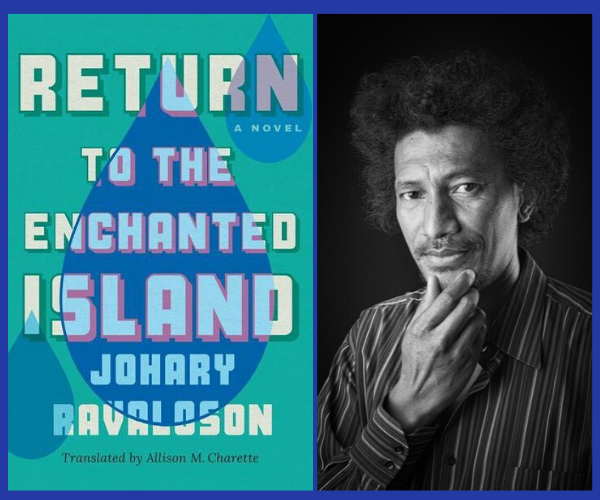

In September 2019, we brought news of the English translation of Johary Ravaloson’s Return to the Enchanted Islands — the second novel in the history of Malagasy literature to achieve the feat of being translated into English. Originally written in French, Return to the Enchanted Islands is, in the words of Amazon Publishing publicity lead Lucy Silag, “a short yet extraordinarily rich tale weaving Malagasy storytelling traditions with a contemporary young anti-hero, giving readers the chance to explore the complexities of eastern Africa in a fresh way.”

Return to the Enchanted Islands is translated by Allison M. Charette, founder of the Emerging Literary Translators’ Network in America, a networking and support group for early-career translators. Here, we present an exclusive excerpt of Charette’s translation of the novel, courtesy of Lucy Silag and with permission from Amazon Crossing.

READ THE EXCERPT BELOW.

The Razaks’ loyalty, which harbored the same ambiguities as their long history, troubled Ietsy. But only a little—it was only ever a small pebble in his shoe. As a child, he went to the Protestant church on Sundays and to Catholic mass on Thursdays at his school (Sintème, which had overseen the education of his father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and all of the country’s elite since colonization). But his father’s most essential entreaty was to not forget the great crossing and the source of unending milk and honey. The god on the cross had been welcomed into the traditional pantheon with the others. The Jesuits charged with Ietsy’s education nearly turned him into a skeptic, but after enduring several trials, his ancestors’ protection proved extremely strong.

He was probably around eleven years old when he saw concrete evidence of it for the first time. The way people in Anosisoa obeyed his every whim obviously didn’t count; that came more from their attachment to financial stability than a fear of invisible, wrathful beings harassing anyone who would try to thwart the blessed one.

There was a guy in the grade above him, mixed race, burly, built, a full head taller than him. He acted all tough and unaware of Ietsy’s natural birthright. One lunchtime, while the other guy was walking home with a few friends to his white vazaha neighborhood next to school, our doubting Thomas sat on the hood of the car and told the driver—often under pressure to shift between Ietsy’s desires and his responsibility to the father—to follow them, and to only pass them once they’d gotten a little ways away from the pink brick outer wall of the hallowed school. Ietsy got all fired up by the stares of the crowd as he passed by like in an Independence Day military parade, confirming his divine and ancestral consecration in his heart of hearts even before completing that first trial. Once the car reached the other guy, Ietsy stood up on top of the roof and hurled insults at him. Everyone following behind was too captivated and surprised by the scene to yell at them to clear the road; perhaps some of them had recognized Mr. Razak’s car. None of that mattered to Ietsy. He continued his diatribe, calling upon the gathering mob as witnesses to the cowardice of the other guy, who didn’t understand the situation fast enough. Then, when he finally opened his mouth, Ietsy jumped him. From the car, he had enough momentum to knock the guy to the ground and pummel him. The driver hoisted himself out of the car and pleaded with Ietsy to stop, while at the same time preventing anyone else from intervening or laying a finger on him, giant that he was. Ietsy left the other guy with blood running down his face.

That afternoon, no one at school talked about anything besides the supernatural trial that had happened. The victim’s parents complained to the rector, but he sidestepped the issue: extra muros, outside his jurisdiction. During his sermon at that Thursday’s mass, he made only a brief allusion to it, staring hard at the blessed one among the rest of his students. Ietsy pretended not to understand.

The young vazaha never had a chance to exact revenge. The driver, in defiance of regulations, started waiting for Ietsy right at the door to his classroom, too afraid that some accident might befall his master’s son. The rest of the time, his friend Nestor—whom they called Thor or Néness, depending on if they were emphasizing his strength or klutziness—towered behind him like a real bodyguard. Besides, they were reminded in their studies that violence was a crime, and as the fat headmaster Brother stressed, the punishment—suspension from school—could be permanent.

The following year, the parents of the vazaha boy—colonie by default, that was what they called anyone who was forced to tolerate everything that someone else did—pulled him out of Sintème and enrolled him in the French high school. The Gods’ and Ancestors’ protection fell unquestionably within the realm of perfection.

Three years later, the blessing was confirmed a contrario, as he would later tell it (with linguistic habits acquired on the bench at law school, people might think, as Ietsy was supposed to get his law degree like his father, if they didn’t know that his exposure to syllogism dated back to childhood, to long lunches in Anosisoa when, while Mr. Razak and his guests binged on clever debate and florid words, Ietsy and his friends pigged out on food and learned the strange effects of alcohol, Ietsy making a valiant effort after several swigs of the paternal whiskey to stay straitlaced until the soft rays of the setting sun streamed into the room and flooded the white plaster wall before going dark). That year, which would end up being his last at that school, he was less bored: there were girls, and a new kid, Arthur, another mixed guy who’d gone in the opposite direction of the ex-colonie, from the vazaha high school to Sintème, and introduced them to the forbidden world of smoking.

I’m obviously not referring to tobacco—which also wasn’t tolerated, outside of the rector’s office—but about what no one smokes anymore besides gangs and guys who haul pushcarts, to avoid feeling fatigue. And artists, too, for inspiration—like the new kid’s parents.

When Ietsy visited their house, he didn’t get a chance to see Arthur’s father, a theater man. His mother, on the other hand, a painter—he often caught sight of her in her studio in the back of the garden, from which the scent of the Ancestors’ weed sometimes wafted. Art was a foreign milieu for Ietsy; he only knew that the paintings that hung on their walls in Anosisoa, which some of his father’s friends drooled dumbly over, were worth a lot of money.

He fantasized more about Arthur’s mother, who wasn’t just an artist but a redhead too. She was from the north of England, near the Scottish border. Her ancestors had fallen in love with the Malagasy sky as they got closer to it during the era of the London Missionary Society. In the first part of the nineteenth century, the awful Queen Ranavalona I had driven out the religious zealots of the Queen of England beyond the seas, for fear they might win over her own subjects’ hearts. By following in their tracks back to the island, Ms. Jones was chasing an old family dream. But of course, no matter how blessed the young Ietsy was, she was naturally out of his reach.

Thursday afternoons in Arthur’s room, with no classes, there was Jeannie. She was the most shameless of all the girls in their class, who’d only started to be dropped into high school in their third year, a few at a time. Jeannie was hitting the joint with them, and it had a fantastic effect. She wanted them to touch her, kiss her. The others thought it was funny, especially Néness, and Arthur too; not Ietsy, he’d always been put off by group work. He watched them, or listened to Charlie.

It must be said that andzamal causes very weird sensations. The cannabis caused Ietsy, already a naturally contemplative person, to be so engrossed that he could watch flies mating for centuries. As for Charlie, he couldn’t stop reading, poems or other books he’d grabbed from the library that lined the hallway to Arthur’s room. Sometimes he would unveil the beauty of a text out loud to his friends, but they’d laugh “at anything and everything,” he had said, annoyed. Ietsy didn’t hear anything very well or feel anything specific, neither agreeable nor disagreeable, as if he were far away, but when the others laughed, he spasmed too, for no apparent reason, and, like the others, sometimes without stopping for an eternity.

Charlie thought they were morons and kept repeating that poetry was the only thing worth anything at all.

“A poet, while the rest of the world wallows and bathes in muck,” he told them, “a poet takes a dump standing up!”

The others rolled around laughing, without quite understanding why. It had become a conditioned reflex, even without the stimulus of cannabis. The instant there was the slightest lyrical allusion, they’d exchange glances and laugh hysterically.

They’d had to memorize a poem for French class. The day it was due, the teacher asked for a volunteer to recite it. She was undoubtedly thinking of Charlie. Before anyone else reacted, though, Ietsy raised his hand, suddenly inspired by the text. He’d barely read the title. He wanted to blow everyone away, especially the pretty teacher whose copper-colored hair made him think of Arthur’s mother. She didn’t let any of her surprise at her student’s unexpected enthusiasm show, just invited him to come to the front. He stood in front of her desk so that she could see only his back. Before the class—ready for anything, knowing him—he began his performance. He lowered his eyes, pretending to concentrate, then, staring hard at Jeannie and Arthur with the most constipated expression—he knew there was no point in looking at Néness—he barked, “Invitation to the Voyage!”

His comrades burst out laughing, followed of course by the entire class. He huffed, acting offended but unfazed. Once the room was calm, he started over. He didn’t have to make sure they were paying attention anymore. He kept his eyes half-closed and made a face as he intoned the first syllables again, letting the next line tumble out in a rush of relief. And again, to widespread hoots of laughter. He turned around and gave the teacher a mock-hurt look, but of course she hadn’t seen anything and was just tapping her pen on her desk.

“Well, go on!” she cried.

He let a few quiet moments pass, then continued his act. Arthur was bent over double from laughing, Jeannie had tears streaming down her face, and Néness was smacking the table and his thighs. Everyone, he thought, was laughing. It was contagious. Even the teacher had a hint of a merry smile as she renounced her plan and told him to take his seat.

As he returned to the back of the classroom, he saw Charlie’s strange expression, but riding the euphoric success of a schoolboy, he hadn’t thought anything more of it. He just wondered if his friend, too, had been smoking before coming to class.

One afternoon a few days later, Arthur brought over some “super-high-quality” stuff. It was just after Easter, and the rainy season was well over by then. They’d never smoked inside the school grounds. As they were enjoying it in the shadow of the pine trees above the soccer field, the quietest corner at Sintème, the poet of the group took some pills out of his pocket.

“With these,” he said, “it will be a spleen explosion!”

They didn’t know what that meant. They were already soaring. They’d missed the start of class. Charlie was telling them about his own experiments, the rest of the group was laughing. Ietsy was with them and sometimes with himself. Probably everyone else too. Jeannie, between Néness and Arthur, was touching herself on the blanket of pine needles. When Charlie gulped one of the tablets down and held out his hand with the rest, she took her own hand out of her pants to take one and swallow it. Jeannie certainly didn’t have cold feet. Ietsy hesitated. Néness took one, and finally Ietsy did too. Only Arthur demurred. He preferred it au naturel, he said, rolling another joint. No problem, they were open to anything, time had stopped. Then, Ietsy thought, he fell asleep.

Néness was the only one who’d actually slept, Arthur told him later on the phone.

“You guys completely lost it. Especially Jeannie!”

Ietsy had only a faint idea of how they’d lost it. He woke up at home under his bed; he had a headache and felt exhausted. Snippets of scenes were coming back to him, but he didn’t know which ones were part of reality. He thought maybe he’d cried at one point, and at another, he’d been naked as the day he was born, racing against an equally naked Jeannie and Charlie.

“All the fathers and brothers in the school were chasing you around the courtyard with blankets,” Arthur told him, screaming into the receiver with laughter. “They wanted to get your clothes back on, but you didn’t make it easy for them!”

Apparently, once they were corralled beneath the Jesuit inquisitors’ eyes, caught and covered—everyone except Néness, who was probably still snoozing under the pines—Jeannie stood up and pissed in the rector’s office, singing all the while.

Ietsy didn’t remember that at all. He listened to Arthur, shaking with nervous laughter that made him bang his head against the mattress slats. He got a nice bump, but not enough to make him move or think it was any less funny. On the other end of the line, Arthur also cackled with laughter, like during their finest hours.

“We’re gonna get kicked out!”

But even that he said laughing hysterically. Neither of them was yet aware of the tragedy.

Ietsy, suddenly hearing his father’s heavy footsteps coming up the stairs and then in the hallway, smothered his laughter with his hand and, still under his bed, slammed the phone down and tried to look apologetic. He heard the click of a key in the lock. Mr. Razak walked in, livid, in one of his eternal dark suits, his mustache and goatee unkempt from rage. He wrenched the telephone out of the wall and took it out of the bedroom, his son unable to hold it. The door slammed, and the lock snapped shut.

Ietsy crawled carefully out of his hiding spot, which wasn’t actually a place to hide because the old-fashioned bed, too tall and not wide enough, hid nothing from view. He started asking himself what he’d intended, choosing a refuge like that, when the key turned again in the lock.

His father entered, followed by two maids and the houseman, stooped and slow. The master of the house strode over to the wardrobe without a single glance at Ietsy and opened both its doors. The others, their job obvious, scooped up all the clothes they could find, including everything on the floor, the chair, and the desk, bringing all of it outside. Each of them made two trips, the man throwing fearful looks at him as he passed, while the women lowered their eyes, one respectfully and the other, the younger one, hypocritically, unable to keep a smile away from the corners of her mouth. His father stood rigidly before the armoire, as if trying to bore his anger through the sandalwood. Silence hung heavily over the swishing fabric.

Ietsy didn’t react, too dumbstruck. He figured he must still be under the effect of the drugs, literally hallucinating. Once his wardrobe was emptied, everyone left and the door was shut, locked again. Then he realized he didn’t even have boxers on, and his other things had already been stripped from the room. They’d probably looked for narcotic substances he might have been concealing. But he hadn’t reached that point; for him, he was only trying things with friends to have fun. So there he stayed, naked and cut off from the outside world.

The only contact with the outside that his father permitted was the plates of food slid in and furtively removed by a wordless, terrified servant, and the old chamber pot that had been used just before his great-grandfather’s final days (in his final days, he’d worn diapers, which a nurse changed for him like for a baby). He racked his brain for a good strategy: Would it be better to rebel, scream, throw the pseudoindulgent food against the wall, do the same with the shameful pot and its contents, then jump out the window and leave a scandal outside in his wake, or do everything at the same time? He’d certainly done enough already. Upon prudent consideration, he decided it would be rather dangerous. He was on the second floor, more than twenty feet up; the Razaks had high ceilings. For a moment he decided to bend, try to mount some sort of defense, but nothing came to mind that would ever withstand his father.

After the third day, it was getting to be too long, and he prepared to go on the offensive. But instead of the regular Quasimodo, the housekeeper was the one who poked her head, ageless even back then, through the door of his room around noon. She didn’t bring a meal, but clothes.

“Your father is expecting you in the library,” she said, her voice as misty as her eyes.

She likely had strict instructions too, because she said only that, then slipped back out and closed the door behind her, but without touching the key this time. He quickly got dressed and mentally prepared himself for war.

His father was playing quite the game, even making him wear his dark suit, the one Ietsy had worn a few months earlier for the funeral of his incontinent elder. He dragged his feet down the stairs. Upon seeing him, his father, in shirtsleeves but a knotted tie, rose from his armchair. Walking toward the living room, he let one sentence drop casually as he passed: “We’ll have a quick bite to eat, and then we’re going to bury your friend Charlie.”

It was as if he’d been struck by lightning. He wondered if he’d heard right. He couldn’t believe his ears, but he couldn’t hope that it was a joke, either. If it must be spelled out, Mr. Razak was as much a prankster as Jeannie was Mother Teresa. And although he would sometimes laugh with his guests, wielding a type of humor that was not shared with his son, he was not in such a mood that day. Ietsy followed him unsteadily. His head was spinning, his heart racing. His father already sitting and the housekeeper waiting, standing in front of the door to the serving pantry. Water looked like it was trickling down the chandelier above the table. And the light that normally poured in through the high windows had become fuzzy. He didn’t realize it was tears, forced out from his eyes without him noticing, blurring the scene until they fell from his cheeks to form clearly visible wet spots on the shining wood floor, brushed daily with abrasive coconut husks and rubbed with beeswax every Friday, the tiniest things in the Razak household often becoming such regular, scheduled routines.

The last time he’d cried like this, he must have been seven or eight years old. For his bad behavior, serious enough that his father promised him a thrashing, he’d been banished from the table and sent to his room to wait. The patriarch had never hit his kid before, but that time, he truly seemed ready to strike.

As he sent him upstairs, he’d added, “I won’t take off my belt just yet.”

He’s going to kill me, the child had thought. His fear had made urine run all the way down his jellylike legs as he climbed the interminable staircase, and his reddened eyes flowed like waterfalls. He kept crying for a long time on his bed. So long that he’d fallen asleep, exhausted. When he’d woken up later in the afternoon, his father had already gone back to work, and he didn’t know if the sentence had ever been carried out. He never knew. The housekeeper had never really revealed anything, only grousing that he’d deserved to be punished, and he’d made sure not to question the primary individual.

This time, adolescent Ietsy dared to ask his father a question, choking back sobs: “Are you going to kill me too?”

Mr. Razak didn’t reply. Still, setting down the fork he’d been bringing to his mouth, he merely gave his son a strange look. It was clearly very inappropriate.

But Charlie hadn’t been killed by his own father, either. At least, not really. His friends whispered during the funeral that the man most likely would have done it, if it would have prevented a scandal. They wondered if murdering his child would have caused the minister of youth and culture less indignation than his son of dying of an overdose. Children of powerful men, no matter what the father’s position, were allowed to do anything, even favoring death over life, never mind what the priest said, clearly obligated to focus the mass on the temptations of artificial life.

Arthur had managed to communicate with Charlie shortly before the tragedy. He was locked up and stripped of all his belongings, like Ietsy. His books, his beloved books, they’d taken Baudelaire, Burroughs, and the others from him. His parents believed them to be the source of his insane debauchery.

“Even Rabearivelo, a national treasure!” added Arthur, who now saw himself as the only one with any knowledge of such matters, because of his artist parents.

Charlie’s misfortune was still having a key that opened every door in the house, particularly the one to his parents’ bedroom, where he’d gone to procure the pills for his final trip.

Arthur’s mother, who’d also come to the burial, refused to join the line to shake the hands of “those people” after the laying of the body in the family vault. The black she wore made her pale skin shimmer. Despite her proper bun tied up at her neck, she was making Ietsy melt like fat in the sun. He would have followed her like a puppy dog forever if Arthur hadn’t elbowed him in the ribs.

The thinning group of friends talked a little on their way to where the cars were parked. No one had heard from Jeannie. Arthur and Néness already knew their fates. The former was going back to the French high school. His parents had questioned him at length, but he was a lucky bastard and got the love part of tough love. The latter was staying at Sintème like nothing had happened. He even got to keep his scholarship. In the nude chaos that had followed their experiments, no one had noticed his absence from class. Arthur, the only one in any state to answer the questions they’d been subject to in the rector’s office—in between uncontrollable fits of laughter—hadn’t mentioned him. So Néness had just kept sleeping under the pines until cold rain woke him up. He hadn’t returned home until nightfall. The next day at school, he first heard the rumors in the courtyard, then in the auditorium the official version about the group’s misconduct, then the final disciplinary action directly after. The other students were unnerved: drugs at Sintème, it was simply unthinkable for most of them. When Took, the class wiseass, tried to rechristen the courtyard the “Garden of Eden,” he and Néness were the only two who’d laughed. Everyone else had glared daggers at them.

It was the last time that Ietsy Razak saw his friends for a long while. The next day, after his father made him take a handful of red dirt from near the ancestral tomb, he put Ietsy on a plane to a boarding school beyond the seas, run this time by Benedictine monks, on the banks of a river that disappeared underground.

Follow this link to order Return to the Enchanted Island.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions