“Do you not want to ever see me again?” my mother said to me on the phone one day in late 2008. She was in Eritrea. This was a few months after the publication of my first novel, The Consequences of Love, about the everyday life and the sexual awakening of a young Eritrean immigrant in the gender-segregated society of Saudi Arabia. A relative living in Europe had just rung her urging her to rein me in.

Writing from my new home in London, to which I had arrived as an underage immigrant in 1990, I never thought about the consequences of my words on people I loved who were in my home country. The freedom in my adopted home was like a curtain I drew over my background.

“I am British now and will write what I want,” I said to my mother.

My mother and I have separation woven into our lives, going back to when I was three and she left me with her parents in a Sudanese refugee camp to go and work in Saudi Arabia. Six years later, we were reunited in Jeddah, only to be separated again after five years, when, fearing deportation back to the war zone by her mercurial employer, a Saudi princess, she sent me with my 17-year-old brother to London. It would be 15 years before we would see each other again.

But now, like the war, poverty in the camp, and the abuse of immigrants in Saudi Arabia, my writing was wedging further distance between my mother and me. This, given the difficult politics back home, seemed an act of selfishness.

With my second novel, I would do things differently. I began to pick themes I thought would be inoffensive to the Eritrean government, choosing words that would not prevent me from seeing her again. Chained to my need of a mother’s love, my characters became the prisoners of my conscience. A battle ensued between the writer in me and the needs of a son. Overwhelmed, I put my novel aside and silenced the writer. Until I moved to Brussels in 2009.

As if inspired by this further exile, my imagination took the idea of the novel I conceived in London in a disturbing direction. I knew that to write it, I had to enter the world of my characters void of all the values I had amassed. And that to negotiate past the taboos and boundaries obfuscating my imagination, I had first to silence my mother’s voice in my mind, a voice I missed, a voice that had become censorship.

Writers kill off characters all the time. I am used to the bloodless disposition of characters that I bury inside me. My chest is an overflowing cemetery. It is a different territory, though, to feel the need to dispense of a mother this way in pursuit of integrity. But I had to be either a son or a writer. I couldn’t be both. Not with this book. I had to bring my three- or four-year-old self to mind to let go of my mother. I remembered the day she left the camp, when I wept as I ran after the lorry disappearing with her down the dusty road. Now, in Brussels, it occurred to me that since that day, my mother had become no more than a memory, like my father who died when I was two. Without mother or father, I was the child of my own imagination, the only constant in my life and on my journey. Assuming success of the triumph of the writer over the son, I began writing in earnest.

But after I finished a writing session, I found no joy in my words, no delight at giving birth to sentences and characters that felt complete to me. Words ceased to be my solace. It seemed that no crime, even one as surreal as killing off a mother in one’s own head to free the path for imagination, is committed without consequences.

Exploring ideas in my work seemed like exposing my people back home. Creating a written story on blank pages felt like the dismantling of my society. My novel was like a double-edged sword that I turned against the traditions of my people for denying the truth of my characters to exist, and against myself for telling lies manifested as truth.

Yet I sought relief in writing, just as I had sought shelter in a refugee camp, from the war. Writing and literature became a safe haven for my imagination. Every word on the page anchored me, and with each chapter, I felt more grounded in my own creation. I had erected my hut on the pages, amongst my characters. Here, I wasn’t a refugee, or an asylum seeker, or an immigrant, or a scar on the consciences of Europeans, or an open wound in the chest of my mother. Here, I was just a writer. And a human being. This was my world, where I had the control over the destiny of my characters, which I never had in my own life marred by repeated exile.

I made progress with my novel. But the cycle of pain and joy started to inscribe itself on my body, and I became sick. I lost over 16 kilos. Thin, famished of a mother’s love, but hunched under the self-attained freedom to write what I wanted, I persisted. And the journey of writing the book inside me prolonged itself until I no longer knew if I was writing the book, or if the book was rewriting me.

But then, when I finally sent out my novel, I found myself facing still more censorship.

After Saudi Arabia, where nuances of life were censored into a black and white world, in London I felt a spark of colour in my imagination. I basked in this freedom. I felt British even before I received my official documents, because my voice found its home and my mind its natural habitat. And yet when I finally became a writer, I discovered that, as a non-white writer, I wasn’t free to write what I wanted after all.

If I wanted to sell my second novel, I was told, it had to satisfy a Western reader’s expectations: confusing, uncomfortable themes must be avoided. I had to desensitise my setting—a refugee camp—so that it fitted the popular view of this reader. I felt my imagination shackled to the desires of this imaginary Western reader, and my freedom limited by the publishing industry’s view of them. I knew enough of real-life readers, though, to know that this was grossly oversimplifying them. Had I not become a Westerner myself?

“Our ideas don’t work for our own culture or for here,” my brother, also a writer, once said to me. “We are shot at by both sides.”

I took my book and walked away from those who tried to censor my imagination, in the same way I had cast aside my mother’s pleas. And I kept walking with my book until I found it a home where words are—truly—free.

This essay was first published in Free Word with the title “Shot at by Both Sides.”

About the Writer

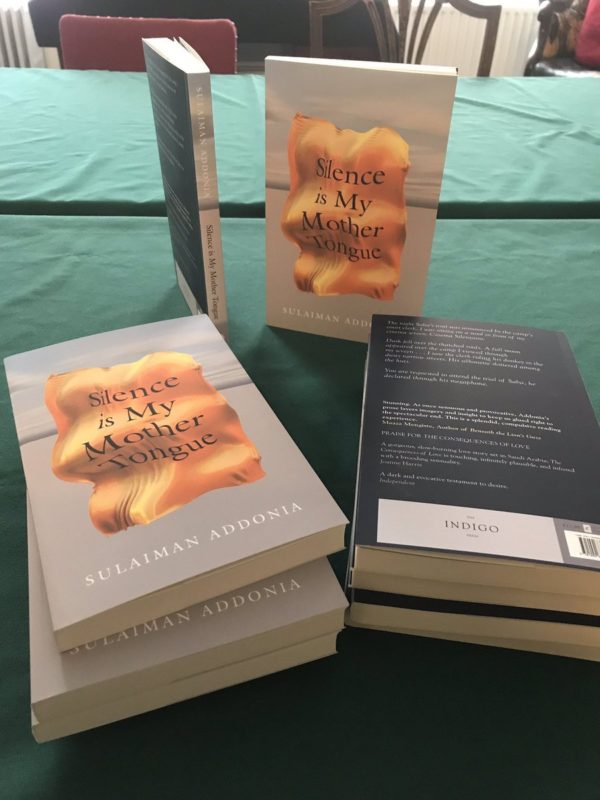

Sulaiman Addonia is an Eritrean-Ethiopian-British novelist. His first novel, The Consequences of Love, shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, was translated into more than 20 languages. Silence is My Mother Tongue, his second novel, has been longlisted for the 2019 Orwell Prize for Political Fiction. His essay, “Writing Like Degas Paints,” is shortlisted for the 2019 Brittle Paper Award for Essays & Think Pieces.

He currently lives in Brussels where he has launched a creative writing academy for refugees and asylum seekers & the Asmara-Addis Literary Festival (In Exile).

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions