The emergence of A Nasty Boy, the fashion magazine founded by the Nigerian journalist and lawyer Richard Akuson in February 2017, ushered in a conversation on the dynamics of gender and nonconformity. With its textured, soulful images, often of men being vulnerable and in poses that demystified norms of masculinity, it was also a new dawn in Nigerian fashion aesthetics. Hushed at home, in a country where being queer carried a 14-year jail sentence and the risk of physical assault but one in which the magazine had amassed major following, A Nasty Boy became an international sensation, covered in CNN, in BBC, in i-d, in Dazed Digital, in The Guardian, in OkayAfrica, in Vogue, and its provocative visual storytelling praised for challenging social conventions.

Knowing opposition to such conversations from his time as a fashion editor at Bella Naija, Akuson, 26, deliberately chose a “disarming” name in “A Nasty Boy.” In interviews and profiles, he made it clear that this is a fashion magazine concerned with aesthetics in its visual curation of the fluidity, complexity, and diversity of gender and masculinity. But towards the end of 2018, the A Nasty Boy website went offline. In April 2019, in a harrowing piece for CNN, Akuson revealed that he was assaulted by four men in his hometown in Nassarawa State, on the accusation that he was “spreading a gay agenda,” and had consequently left Nigeria. In another essay for The New York Times, prominently placed in its print edition and on the homepage, Akuson reflected on homophobia and familial censorship. The magazine’s colourful archive of defiance continues to exist on Instagram.

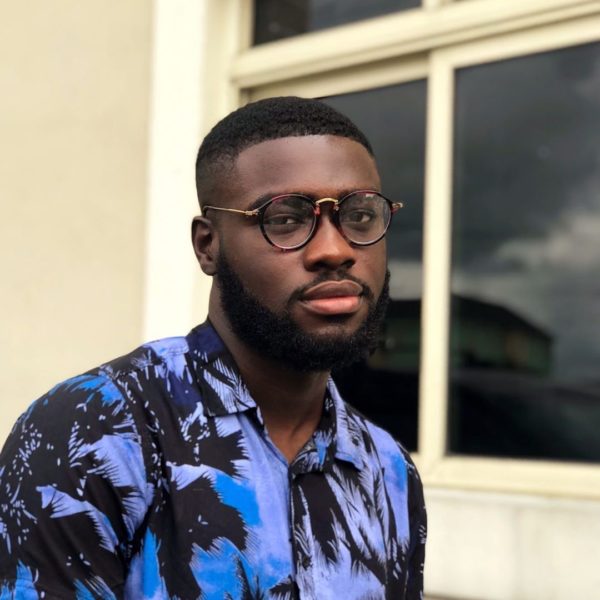

https://www.instagram.com/p/BzneGxkAPEI/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

This new year, January 2, Akuson, a 2019 Forbes Africa “30 under 30” honoree and 2017 The Future Awards Prize for New Media finalist, announces his successor in an exclusive to Brittle Paper. “Since fleeing Nigeria, I’ve been faced with the difficult choice of either continuing as the editor and publisher of the platform—consequently, writing about an experience that I’m no longer a part of—or finding a successor who will bravely steer the publication and, by extension, the vision I have for it forward,” he wrote in an email to us. “Believe me when I tell you that I’ve searched everywhere for someone I can entrust with this very personal vessel. I’m ecstatic and genuinely proud to introduce you to Vincent Desmond as the new editor and publisher of A Nasty Boy.”

At only 20, Vincent Desmond has acquired a reputation for his journalism, which explores sexuality, gender, identity, and culture, in pieces spanning print and digital publications from VICE UK, Dazed, and i-D to AnOther, OkayAfrica, and BellaNaija Style, where he was a staff writer. Last year, TIERS Nigeria named him its Young Trailblazer of the Year. This year, RED Media Africa co-founder Chude Jideonwo listed him among “The 150 Most Interesting Nigerians in Culture in 2019.”

“I was drawn to Vincent as my successor not only for his demonstrated promise as a journalist but also because of his courageous and incredibly thoughtful portrayal of our lived experiences as LGBTQ+ Nigerians,” Akuson says. Desmond’s “fearless and responsible advocacy through the written word” is “a desperately needed panacea for the pernicious portrayal of queer people in mainstream Nigerian media.”

“While the founding vision of highlighting the complex lives and radical existence of LGBTQ+ Nigerians that is at the heart of A Nasty Boy will not change,” Akuson says, “how this is shaped or presented, or even the stories that are told, will be entirely up to Vincent from here onward. I will stay on, briefly, as editor-at-large until the new A Nasty Boy is launched on February 19, 2020, which will be our third anniversary, assisting Vincent in the background to bring his vision for the publication to life.”

Akuson and Desmond gave us answers on the direction of the relaunched magazine.

Otosirieze:

We are so sorry, Richard, that you had to endure assault in Nigeria and had to leave. You have since written about it for The New York Times. Your resolve has always been strong; how has your recovery and the public response strengthened it? How have you been, generally?

Richard:

Thank you so much for your kind words. Frankly, I’ve never felt better. I’ve never been as connected and in touch with my body, mind, and surroundings as I was in 2019. Of course, this means that I feel things even more deeply now and I’m extremely present in each and everything I do or experience—and, granted, I owe this new awakening of my mind and body to a soul-crushing experience that shattered the meticulous life I’d created for myself in Nigeria—but if there’s to be any silver lining in this story at all, it would be this. Junot Diaz wrote, “Repair is never-ceasing.” And I agree! I’m still healing, restoring, recovering, and repairing every day—I am still developing the courage to admit I still love Nigeria, deeply even. I close my eyes every time I miss home and try to recall the streets of my childhood neighborhood in Akwanga, places I enjoyed going to in Abuja and Lagos, and even the smells and sounds of friends, things, and places. I’m trying to race against forgetfulness and relish my fondest memories of Nigeria while I still can. I’ve also had to work through blaming myself for what happened, but I know now that blaming myself was simply a matter of convenience. I mean, it was easier to blame myself than to do the hard work of unpacking the conducive, toxic socio-cultural factors that embolden homophobia to thrive and flourish in Nigeria.

This is why A Nasty Boy is as relevant today as it was three years ago when I launched it to combat the misinformation and negative portrayal of otherness in Nigeria, which I’m confident Vincent will continue to champion with as much resolve as he can muster.

Otosirieze:

Richard, you have talked about your difficulty securing funding, with potential sponsors deeming the magazine “unnecessary.” Did it affect your plans for the biannual print issues? In what ways, Vincent, might the problem of funding shape the formal return of the magazine? Will it?

Richard:

Yes, the lack of sponsorship did affect the short-term goal of going into print. Yet, I have never wavered—not even for a second—in my belief in A Nasty Boy or its role in championing positive narratives of the beauty and radical existence of LGBTQ+ Nigerians. For this reason, I was determined to go into print for our readers who wanted to carry our stories with them everywhere they went. In fact, part of the push to go into print was because of the interest we were getting from research institutions, universities, and bookshops from around the world who wanted to purchase copies of A Nasty Boy for their libraries, and so on. Ultimately, I believe all things happen in their time—and Vincent will be ready when the time comes.

Vincent:

It will and it will not. Granted, having ready funds would make operating and running A Nasty Boy easier and would allow me to start off with particular and more financially-draining projects, but make no mistake, we will undertake those projects regardless and eventually. I plan on drawing on Richard’s experience and mine as well to think out of the box to raise the funding we need to ensure that A Nasty Boy is up and running and, more importantly, stays up and running.

Otosirieze:

A Nasty Boy has come to embody ideas about gender and nonconformity, and has also had sexuality mapped onto it in the media coverage of its impact, but it is firstly a fashion magazine pushing aesthetics with new talent. You make sure to state this clearly, Richard, and it is extremely important because queer culture is easily and mostly repackaged heterosexually—we are reduced to being The Resistance and not recognized primarily as innovators on an equal footing with heterosexual artists. It is cultural erasure to presume for us when and how we could be artistic or political, as if we aren’t already both, and this happens alarmingly in literature, for example. How will you approach this, Vincent?

Vincent:

My background—just like Richard’s—is in fashion media. I have spent most of my career as a writer and journalist covering fashion, and I have taken it as a mandate to highlight and archive how queerness and queer people serve as innovators within and beyond fashion and culture. With A Nasty Boy, I plan on building on this experience and the amazing foundation Richard has laid to further the telling of these stories and to highlight the work of queer artists and talent, all the while disrupting this heteronormative world.

Otosirieze:

You have also addressed the wider geopolitics of this problem, Richard. You told Dazed Digital: “The true moment of acceptance comes when the fact that it is Nigerian is irrelevant, and people are just responding because of the content.” This suggests that A Nasty Boy is meant to be rooted in its Nigerianness, taking on visual advocacy in an oppressive political culture, while still transcending Nigeria, because its are also comments on the global state of masculinity. How do you think of this, Vincent?

Vincent:

I think the homophobia of Nigerians is unique to Nigeria. It shares common denominators with a global homophobia that affects the global LGBTQI+ community, but it is specific to the Nigerian experience, how our particular history with colonialism, religion, politics, patriarchy all intersect. The dream is that while A Nasty Boy will tackle homophobia as a global concept or phenomena, and while the content at A Nasty Boy will remain universally valid, it will tackle and address this oppression and experience as it is specific to Nigeria. This is very important as A Nasty Boy is one of a few queer-centering publications in Nigeria.

Otosirieze:

Richard told i-d: “The dream is someday being invited to a Chanel or Vetements show, being able to see the pieces up close and give our perspective to our audience.” You have important experience, Vincent, and will be bringing a breathtaking vantage we can’t wait to see. What should we expect from your vision of A Nasty Boy? Where will you be taking us?

Vincent:

The dream is to build A Nasty Boy to a level where we can honor invites from these top fashion houses, commission a writer to attend and cover them, while another is off exploring the implications of some arcane verse of a traditional Nigerian religion referencing queerness, and yet another is breaking down sex from a queer perspective for our readers. The goal is to build A Nasty Boy and its verticals to where we can deliver well-rounded coverage and even go beyond examining queerness in fashion and culture. The dream is to keep archiving and highlighting till we become one of the destinations to come to understand and explore queerness in Nigeria.

Visit A Nasty Boy‘s Instagram.

Joan Camenisch January 03, 2020 03:13

I got this site from my pal who shared with me on the topic of this web page and now this time I am browsing this web site and reading very informative content at this place.| http://www.linkagogo.com/go/To?url=108280117