“Are you coming in or not?” she asked in a seductive tone, three fingers raised slightly above her neck.

I gaped at her and the naked figure squeezing her breast from behind. And then the dying sky. The moon was dancing to an orchestra of dark tunes, and clouds were filling thin cups with lightening balls.

“Come on, Pete. It’s not like I want you. I’m only trying to save you.” I smiled, gazed at them a while longer and turned home.

Once I cornered Odu’s street into the alley of Oriaku’s park, laughter erupted from the far end. It was so abrupt, I’d expected it to end at once. But no, it didn’t. Instead, it grew louder. So loud I had to hide behind a mango tree and peer intermittently at the moon-lit darkness ahead. I continued peering, until a lanky bespectacled man, holding his loose trousers, shouting “ewo! ewo!,’” and cursing in Igbo, emerged from the darkness.

‘Why don’t you go back to Cynthia’s home?’ my racing heart tickled. ‘Stop the man. At least, get to know what danger lies in front.’ It continued. But I refused. Too many times, my instincts have led me into danger’s cruel abode. Too many times. The only day I stopped a boy along this alley, just to ask one harmless question, he ransacked me while holding a dagger to my throat. As soon as he sped past, I stepped out of hiding, and sauntered on—wishing the moon in all of its roundness and elegance talked, the ominous clouds hovering over me like the spirit of death out of crying.

As I approached where avocado and plum trees sat side by side and danced to discordant tunes of fierce harmattan wind, the alley lights came on. I looked at the incandescent bulbs and smiled. But thank God I didn’t leap for joy, as I would have if I were behind closed doors—it dimmed as soon as it shined. The moon walked into the chamber of a sister cloud, and the laughter ceased. It happened so fast, synchronous, as if it were a plot. And in a matter of seconds, I was in the forbidden realm of utter silence and darkness. Trust me. I froze and almost peed my pants. Okay. Okay. I peed a little.

As the warmth trickled down my thighs, memories of the frigid Friday night when little boys my son’s age pulled him from my arms, shot him, and butchered him into stew size pieces struck me. It continued to repeat with the chirping sounds of crickets and heinous laughter that accompanied it, till a heavy truck blared me back into reality.

I stared through the darkness, turned left and right and left and right, clueless, until the moon opened the door. It was then I realized that it wasn’t a plot. If it were, she would have spent more time like she did the night three brown-toothed raggedly dressed boys waylaid me along Okeh’s street and offered me countless slaps that sent jumping vibrations from one half of my face to the other. Instead of just asking for my phone and wallet.

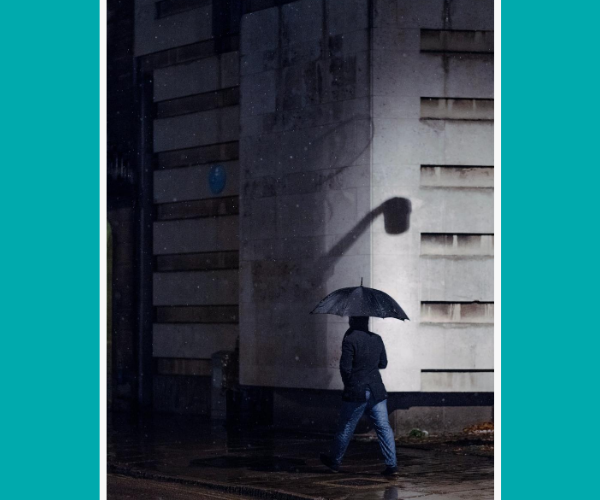

But I didn’t trust the moon. Not tonight. So, I put my hands in my blue jean pocket, broadened my shoulder, and changed my steps into a bounce. The moon finally bid the sister cloud goodbye and lightened the alley again.

I saw the laughers sitting on an old bench, drawing smoke from jumbo joints. Once they noticed my steady gait, three except one ran into the abandoned park. As they ran, they screamed ‘Obembe run! Police! Police! Run!’ but the ruffian-dreaded boy wearing a red t-shirt and black short didn’t. Instead, he drew a bag close, threw the remnant of the joint he’d been smoking, and lit another. He sucked from the tiny end, looked at me from afar, and puffed perfect O’s.

Suddenly, the clouds started chasing the moon as though the moon had stolen their sister’s cup of lightening. If you had seen the velocity with which the moon ran and the skillfulness with which beautiful genies fishing in her golden waters enchanted ancient spells and waved wands to slow the clouds, you would support the clouds.

When I got to where Obembe sat, I made to crossover to the lane that led home. But the painful memories of my little boy’s demise and the softness held behind the redness of Obembe’s eyes charmed me. So, instead, I sat on the bench. Close enough to cross a hand over his shoulder. We were mute for minutes. After silence had tethered our unfamiliar hearts, I asked him why he was out late, smoking. He puffed an O and turned his head to peer deeply into my eyes. The way he did it, his face mapped with mixed expressions, I couldn’t tell if he was angry or trying to determine my creed.

When he had almost exhausted the entire redness of his eyes, he started telling pitiful tales of how weed sheaths memories of his family somersaulting in their car. Of how it blocks flashes of principal Nkaai chasing him out of class two Novembers ago. Even if school was the only place he found solace and had hope of tying his loose lace. And how it keeps him warm on frosty nights. I drew deep breaths, trying as much as possible to stifle the tears that had formed. He looked at me again, differently, with an expression filled with expectance. But I didn’t know what to say or do—couldn’t protect or save my son. I wished he stopped staring at me. But he didn’t. Seconds later, he asked if I were a preacher. Because, according to him, I didn’t look like the police. I smiled childishly and said no.Once the word drummed on the tympanum of his tiny ears, he pushed his hand into the bag and pulled out a revolver.

“So you no be Police or preacher, you come cross those trees. Who you be?”

I shivered at the firmness of his grip. He stood up from the bench and asked me to move. But I’d frozen again, my heart pulling the bars of its cage like the hulk. He gave me a fiery slap that broke the stiffness and started pushing me towards a mango tree where an open umbrella hung upside down.

As we walked, I tried to talk. But he always shushed me. When we got to where the umbrella hung, he whistled wildly, three times.

As all these were happening, the bereaved cloud noticed that the moon was nearing her valley of darkness. So, she started weeping and yelling for help. But before her sisters joined the sullen chorus, I summoned courage from only God knows where.

“Obembe. I once had a son like you, soft and calm. Until he got involved and ended up as stew sized meat along Okeh’s street. I believe you weren’t always like this. Please, don’t shoot me. I can give you and your friends a fresh life.”

Obembe hissed and started laughing. “I know say you be preacher.”

“No. I mean am.”

He gazed at me, turned to look at his friends jumping out of the park and quickly turned back. I saw calm waters rising to quench the flames in his eyes. But the closer his friends came, the more the waters rescinded, and the stronger the stench of death filled the air.

“Obembe,” I called as softly as I would whenever I tried talking sense into my little boy. “I mean am.”

“Shut up make I reason. Or you want make I put bullet for your head?”

I quickly rolled up my tongue and glued my lips. Seconds later, he raised the muzzle to my chest and asked me to put whatever I had on me into the open umbrella. After that, he ordered me to take off my clothes. As I did that, he grinned at me and pulled the trigger.

Immediately, death hugged me and kissed my troubled heart into silent salutation. But in my little boy’s voice, it continuously whispered ‘not today.’

When I woke up the next morning, some people were sitting around me in a hospital room. I couldn’t tell who they were. But, as soon as the cloudiness hazed-off my eyes, and I noticed it was Obembe and the other boys, I died again. As I slowly opened one eye to confirm their identities, they burst into laughter.

“Don’t die again, please, please.” Obembe said. “I didn’t pull the trigger, lightening struck.”

“We all wanted an alternative,” another added.

Today, I’m a fearful father of four fierce friends.

***********

Photo by Craig Whitehead on Unsplash

***********

About the Author

Meredith Chiwenkpe Asuru is an administrator residing in the oil city of Port Harcourt. He loves to dream and write fresh stories, hoping that someday his work will see the light of great publications and be read by many. When he isn’t working, reading, or writing, he is praying for a greater Nigeria or cruising the streets of D-line on Legedez Benz.

Meredith Chiwenkpe Asuru is an administrator residing in the oil city of Port Harcourt. He loves to dream and write fresh stories, hoping that someday his work will see the light of great publications and be read by many. When he isn’t working, reading, or writing, he is praying for a greater Nigeria or cruising the streets of D-line on Legedez Benz.

Sarah Chioma June 06, 2024 07:32

Story of friendship indeed. I hope the fearful father of four, lives not to experience another tragedy. Beautiful piece here Meredith .