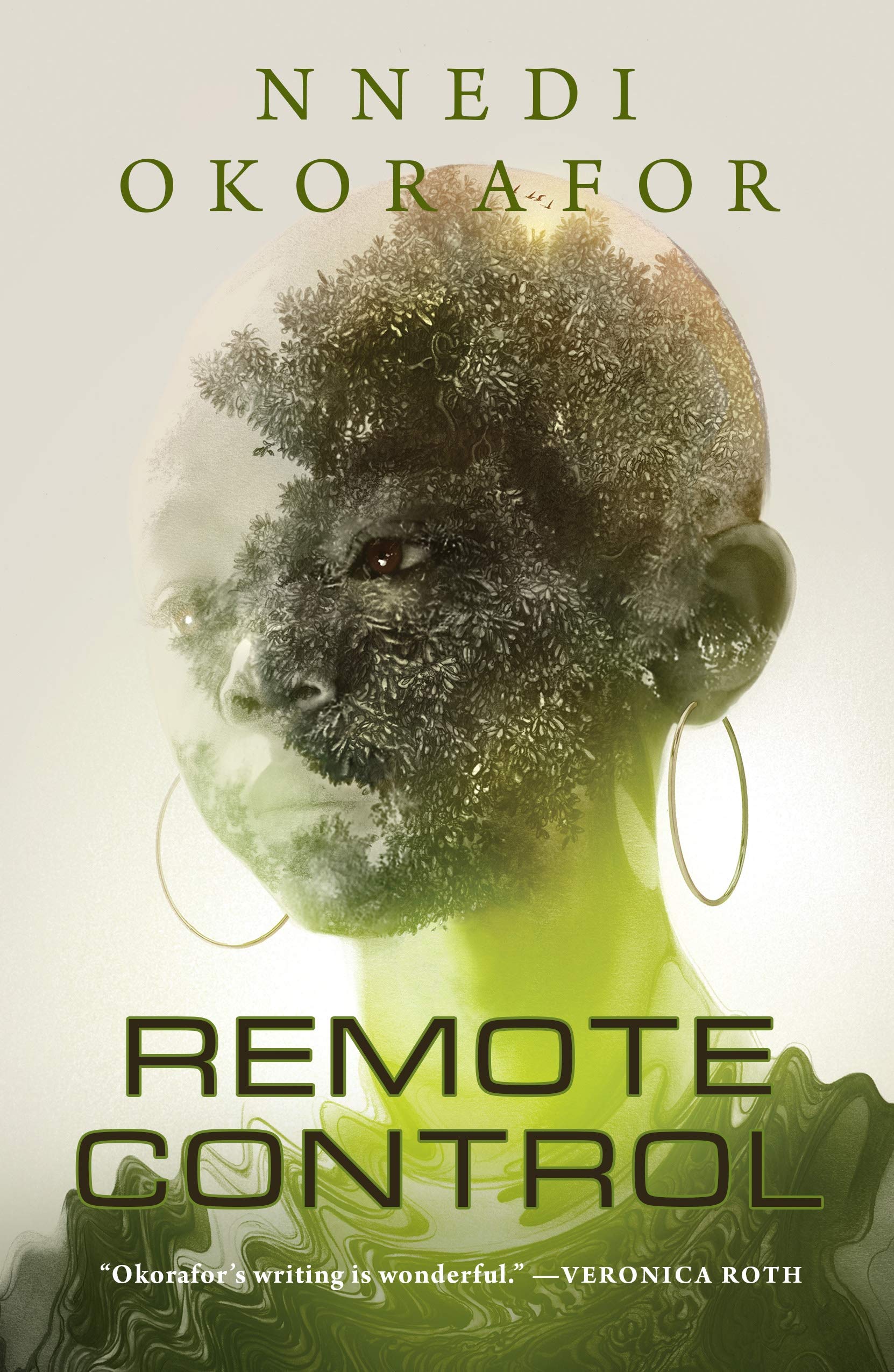

African speculative fiction is a literature of powerful female characters. From Tomi Adeyemi’s Zelie to Lauren Beukes’ Zinzi December, teenage girls wield enormous influence over their worlds. We’ve come a long way from African novels were women’s stories centered on domestic crisis or aspirations. The young women we see in African sci-fi fantasy are world-builders, adventurers, and warriors. Nnedi Okorafor has contributed a lot to this tradition with fan favorites like Binti and Onyesonwu. Her latest novella, published earlier this year, and titled Remote Control introduces one of the most enigmatic of these world-shaping female characters.

Remote Control is an adventure story of a teenage girl with an extraordinary ability. Her name is Sankofa. The adopted daughter of death, she wields the sovereign power to kill. She is sometimes summoned to bring peace to end-of-life sufferers of chronic illnesses by taking their lives. She also uses her power to kill to protect herself and others from predators. While her embodiment of death excludes her from normal life, it enables her to take up space and influence the world. She declares: “I am Sankofa, I belong wherever I want to belong.”

Sankofa was not always a death-dealing prodigy. Her journey from girl to god covers the first part of the story. She was born in Wulugu, a town in northeast Ghana. Her name was Fatima. A child of shear tree farmers, she loved the outdoors. Most nights, she’d climb one of the shear trees and watch the stars. She is a curious child, keenly observant and reflective. Her life changes when the remains of a meteor shower—she calls it the seed—comes in contact with her skin. After this otherworldly encounter, her life quickly unravels. By the time she leaves Wulugu to begin a new life on the road, the city is a pile of dead bodies.

Sankofa makes the story. She is as much a myth to the other characters in the story as she is a larger-than-life force for the reader. Through her itinerant lifestyle, she takes up space. She blows things up, burn things down; in other words, insisting on reshaping the world rather than be constrained by it.

The feminist core of the story lies in Sankofa as a figure of violence. A girl who walks the world with the power to protect herself from harm, Sankofa lies beyond the reach of patriarchal violence. She shows us why it is, perhaps, better for a girl to be feared than to be protected. We can also see why a radical feminist such as Mona Eltahawy would love Sankofa. As Eltahawy argues, in her book Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls, that girls are particularly vulnerable in a patriarchal world. They are caught in a deadly bind, in which they are subjected to violence but socialized to be incapable of protecting themselves or fighting back. The instrument of socialization is the idea of the “good girl,” which is used to deepen the vulnerability of girls in order to abuse and exploit them.

Sankofa is far from being a “good girl.” She is a mix of contradictions. She defies common assumptions about what feminine respectability should be. From the age of seven, she’s lived a vagabond existence. She is the girl with a face “dark and sweet,” but she can be terrifying. She is not giggly or cutesy, but she cares about how she looks: her gold hoop earrings, color coordinated outfits, and striking wigs make up her signature look. She might wield the power of a deity, but she doesn’t take self-care lightly. One of the side effects of Sankofa’s extra-terrestrial encounter is that she is bald, hence the wig. To make the wig less itchy, she frequently applies shear butter to her head, hence “the jar of shea butter bigger than a grown man’s fist” that is always in her bag, alongside “a hand-drawn map of Accra, and a tightly rolled-up book.” Following an encounter with a predator:

She turned away, opened her bag and brought out the jar of thick yellow shea butter. She scooped out a dollop. She rubbed it in her hands until it softened then melted. Then she rubbed it on her arms, legs, neck, face and belly. She sighed as her dry skin absorbed the natural moisturizer.

The image conveyed in this scene is simple, mundane, yet powerful. It evokes a deeply ingrained black feminist idea of care of the self and the body.

Sankofa’s many contradictions evoke an ideal of feminist experience where a woman’s life is left alone to assume a multiplicity of shapes. She is never reduced to the heroics of her strengths, neither is she made out to be insecure. There is enough messiness in her actions and attitude to make her real and relatable. What is more human than the many ways in which we don’t always add up to a perfect being or miss the mark on being a “good girl.”

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions