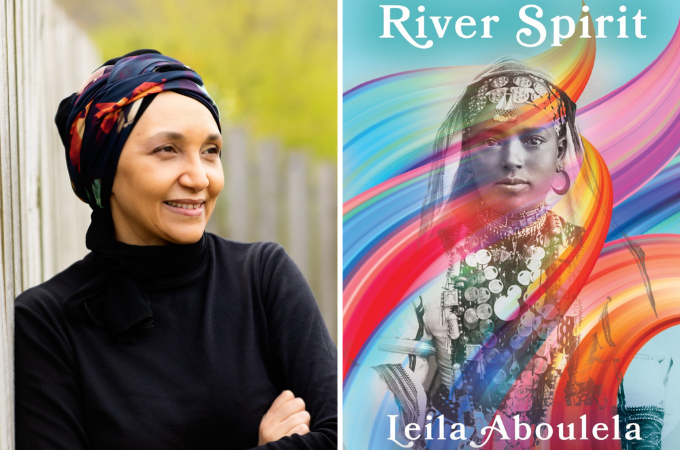

Prominent Sudanese author Leila Aboulela recently published her fascinating 2023 novel River Spirit. In a conversation with Brittle Paper, she shared with us the story behind the mesmerizing title of the novel, the challenges of researching the Mahdist Revolution in Egypt’s history, and the importance of retelling global histories through the perspective of marginalized characters.

River Spirit is a gripping story about an enslaved young woman’s coming of age during the Mahdist War in nineteenth century Sudan. Set against the backdrop of British imperialist history, the main character Akuany and her brother Bol are orphaned in a village raid and taken in by the merchant Yaseen who promises to care for them. However, Yaseen and the children are split apart after he decides to oppose the rising revolutionary leader, the self-proclaimed Mahdi. What will happen to young Akuany as she is sold and traded from house to house across the country? Read the novel to find out.

Leila Aboulela is a Sudanese author whose work has been translated into 15 languages. She grew up in Khartoum, Sudan, and now lives in Aberdeen, Scotland. She was the first winner of the Caine Prize for African Writing back in 2000 and has been thrice nominated for the Women’s Prize for Fiction. Her published novels include Bird Summons (2019), The Kindness of Enemies (2015), and Lyrics Alley (2011), which won the Fiction category of the Scottish Book Awards.

***

Brittle Paper

Hello Leila. Congratulations on the new book. How long have you been working on the book and what does it feel like to finally have it out in the world?

Leila Aboulela

Thank you, Brittle Paper. It’s been many years of thinking, researching, writing and re-writing. I wrote the first draft during the pandemic lockdown and it was great to have a long stretch of uninterrupted time. I enjoyed writing it more than any other book I’d written. It was wonderful to be immersed in the Sudan of that period. Now that the book is published, I feel as if my secret is out in the world. I am delighted especially with how many readers have engaged with the love story thread in the novel. I did not think I was writing a love story but in fact, this is now, I realize, exactly what I’ve done.

Brittle Paper

You are definitely an author who knows how to title books beautifully. What is the story behind the title of this book?

Leila Aboulela

My working title for the novel was Rammed Earth, Smooth River and then I changed it to Rammed Earth, Scorched River and then on submission to Rammed Earth, Two Rivers. No one really liked the ‘Rammed Earth’ part of the title, and my editor Elisabeth Schmitz suggested The River Spirit. There is a line early in the novel when the main character Akuany is introduced, in which the White Nile is described as ‘the spirit of who she was’. I loved the suggestion, but I was anxious that readers would think that ‘spirit’ was a reference to a supernatural being rather than a quality, so we dropped the determiner.

Brittle Paper

The story is set in the Mahdist War of Sudan, a period that is not well-known in spite of its monumentality in the history of colonialism. Can you tell us about that period and why you chose to write about it?

Leila Aboulela

The Turkish–Egyptian government, which ruled Sudan in the 19th century, exhorted heavy taxes on the people, most of whom were impoverished. The Mahdist movement developed in this context and when Muhammed Ahmed Abdallah, the Mahdi, took up arms against the government, his successes were spectacular given his meagre resources. Eventually the Mahdist armies, in 1884, put the capital Khartoum under siege. The British Governor General, Charles Gordon, an employee of the Egyptian sultan held out for months. His plight roused British public opinion and an army was sent to rescue him. Everyday he would stand on the roof of his palace, gazing out over the Blue Nile with his telescope awaiting the relief expedition. When it arrived, it was too late. The city had been taken by the Mahdists and Gordon was assassinated. I grew up with this thrilling story, studied it as school and university. By writing about it, I wanted to share it with a contemporary audience and look at it with a fresh perspective. In addition to this and even though it was not my initial intention, as I went deeper into the research and the writing, I started to see parallels between the Mahdist movement and modern-day insurgent movements such as Boko Haram and al-Shabaab.

Brittle Paper

What does your account of the story add to the existing narrative around the events of that period?

Leila Aboulela

The British colonialist narrative is naturally imperialistic in tone. Gordon is portrayed as a hero whereas the fact that he dug in and refused to surrender to the Mahdi caused the death of thousands of Khartoum’s citizens. Moreover, his death was used to rouse the British public into the need for vengeance, thereby supporting a full-scale invasion of the Sudan thirteen years later and making it part of the British empire in 1898. I had to sift through the propaganda and the self-righteousness to reach a somewhat more sober, unbiased truth. On the other hand, the Sudanese sources could often be uncritically patriotic, glossing over the brutal and tyrannical aspects of the Mahdist revolution and how much terror it spread among the tribes that were loyal to the government. I wanted to focus on the experience of the Sudanese themselves and especially the women. There were little historical accounts of the role of women. This was even though they accompanied the armies during the Mahdist wars. They cooked, nursed and set up market stalls every step of the way. They also played a part in espionage, gathering data and passing it along. Yet, they were only mentioned as footnotes in history or not mentioned at all. For the creative writer, this provided the opportunity to fill in the gaps.

Brittle Paper

Why do you think we need this story at this moment in time?

Leila Aboulela

We are now reassessing the role of the British Empire, looking at it with fresh eyes. We need to hear the stories of Africa’s encounter with Europe from Africans themselves. Mainstream colonial history has been viewed and written through the lens of Europe. This is insufficient for us in these contemporary times and as Africans we need to write our own history. Take for example the 1960s Hollywood film Khartoum which covers the same historical events. In it Charlton Heston plays Gordon while Laurence Olivier, in blackface, plays the Mahdi. It was not filmed in Khartoum, and it shows a meeting between Gordon and the Mahdi which never took place. There are no women. The only accurate details in the film are the weapons! The film is outdated and unacceptable to a modern audience, but the history did take place and the repercussions of empire are still felt today. This is why we need to go back to the primary records and refresh the narrative.

Brittle Paper

People tend to have a homogenous view of colonialism in Africa. But the Mahdist War tells a different, more complicated story. Can you elaborate?

Leila Aboulela

Sudan did not exist in isolation, cut off from the rest of the world. It was part of the huge sprawling Ottoman Empire and the majority of the Northern Sudanese felt an affinity with Egypt and Turkey because of a shared religion. In nineteenth-century Khartoum, there was a higher level of sophistication than we are led to imagine. There were hospitals, schools, a printing press, and significant levels of literacy. There was thriving trade with Ethiopia, Uganda, and with Egypt, extensive travel by boats and by land on camels. There were sophisticated methods of agriculture. Sudan was not an empty, sleepy, passive place awaiting the advantages of British colonialism. And the Sudanese were ready to unite despite their different tribes against a common enemy.

Brittle Paper

Akuany or Zamzam, as she is later named in the story, is black and a slave. Can you tell us a bit about the cultural context of that particular form of slavery and how that went into your crafting of the characters?

Leila Aboulela

When people think of slavery, they are likely to think of the long Atlantic passage and the plantation culture accompanied by deep systematic racism. The East Coast slave experience was different. Capitalism was not the driving force of the Arabs and Ottomans. Instead, they mostly enslaved men for military service and women for domestic labour. Sudan was one of the gateways to the large markets of Cairo and Istanbul, but slavery was practiced within Sudan itself as it was in other parts of Africa. I grew up knowing this and knowing people of slave descent. Almost every Sudanese family has a branch descended from an enslaved mother. Within the cultural context of Islam, a child whose mother was a concubine had the same rights and legitimacy as his half-siblings whose mothers were free. This led to a quick assimilation within the family setting but also carried a legacy of shame so that such matters are rarely talked about in Sudanese society. I came across the character of Zamzam in the Sudan archives at Durham University in a petition regarding an enslaved woman who had stolen a piece of material from her mistress and ran away to join her former master. It made me want to put together a story about her. Early in River Spirit, Akuany and her brother Bol survive a slave raid of their village but because they are orphaned, this puts them at constant risk of future enslavement. Bol is fostered by a loving family, but Akuany’s fate is much more brutal, and she is enslaved by the Turkish Governor’s wife.

Brittle Paper

There is the kind of history that tells the story of great events through the eyes of great people, often men. Why did you choose to anchor such a world-historical narrative on a character who is marginalized in so many ways in her world?

Leila Aboulela

I was drawn to her. I wanted to find out more about the texture of her life and how she interacted with the events happening around her. Because she is not invested in the politics, she is inadvertently a somewhat detached observer and for me that slowed down the historical narrative and made me able to focus on the domestic human details of her life. Part of the problem with the ‘great events’ narrative is the unnatural speed. Expressions such as ‘Khartoum fell’, ‘the army advanced’, ‘the battle was fierce’ doesn’t convey to us the experience of the people involved. Fiction can do that, and a marginalized character gives a greater scope for imagination and the chance to advance a plot that is affected by the great events but not necessarily about them.

Brittle Paper

This is not your first foray into historical fiction. Lyrics Alley and The Kindness of Enemies are very well-known. What would you say is different about River Spirit?

Leila Aboulela

The research was much more extensive with River Sprit. In Lyrics Alley, I was writing about family history, and it was set in the 1950s, so within living memory of many of the people I spoke to. With The Kindness of Enemies, I had primary first-person texts to work with and so I was reassured of their accuracy. On the contrary, with River Spirit I had to wade through propaganda and even many of the primary texts about the Mahdist period were edited, translated and published by British officials keen to whip up support for a full-scale invasion of Sudan, or afterwards to justify British colonialism! It was not easy at all. It helped that I am bilingual and I could access the original Arabic resources and other Arabic sources that had never been translated.

Brittle Paper

Tell us about the writing process. You have been doing this writing thing for close to three decades. Do you find that your process as a writer is changing?

Leila Aboulela

I am much more confident now and ready to take on bigger challenges. I was cautious when I first started to write, playing it safe to a large extent and not taking big risks. Now I am happy to take risks. I also enjoy the writing more and it flows easily. When I first started writing, the words sometimes came out with difficulty and in an uneven flow. Writing used to be a compulsion, sometimes painful and upsetting, more intimate and autobiographical. In a novel like River Spirit, I am not writing at all about myself and so there is more freedom in the writing.

Brittle Paper

Your representation of Khartoum, the devastation of war, and the decadence of Ottoman state power are so real and present I felt like I’d been transported. What went into recreating the world of 19th century Sudan?

Leila Aboulela

I also, while writing, felt that I was transported! Throughout the research I read accounts from different sources – even sources that were politically unreliable or biased were very useful in conveying a sense of place. I also found it helpful to read about the same event from different sides of the conflict and then map the similarities which were often consistent. I wrote the first draft of River Spirit during the pandemic lockdown, at a time when I had very few distractions and I could immerse myself fully in 19th century Sudan. To help me in this immersion I restricted myself to reading fiction that was set in 19th century Africa and also choosing films that were close to the period if not the place. By doing this, I could ‘stay in the zone’ even when I was not working. I have to admit that I enjoyed writing this novel more than any of the others. This was because as I was writing, all the characters and places felt extremely real to me as if they existed in a parallel space, or as if underwater and all I had to do was go to that space or dive there to find out what was happening.

Brittle Paper

Where were some difficult choices made in terms of the conception, crafting, and execution of the story?

Leila Aboulela

I had to make many deletions to the text. Although I thought I was careful, I made the typical mistakes of having information dumps and showing off my research. Through the editorial process, I deleted around 30,000 words. This was painful for me. A lot of good writing was lost but all of that writing was repetitive, historical details that were neither necessary for the plot or the character development. They were interesting details but probably not captivating for the average reader and were slowing down the thrust of the novel.

Brittle Paper

I have one final question for you, Leila. Some of the major African historical fiction published in the last few years have been written by women—Lalami’s A Moor’s Account, Makumbi’s Kintu, Tshuma’s House of Stone, Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, Okparanta’s Under the Udala Trees, Mengiste’s Shadow King, Mohamed’s The Fortune Men, Petina Gappah’s Out of Darkness, Shining Light, and many, many more. This is a major shift from a historical fiction tradition centered on Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. What do you think is the significance of having so many women telling stories of the African past?

Leila Aboulela

When women write historical fiction, they are often centering women’s experiences (or other marginalized characters) and telling their untold stories. They are also often highlighting the domestic sphere or interpersonal relationships, away from the battlefield. Fiction animates and highlights characters who are excluded from the official records. In my historical research, I never came across a first-person account written by a woman! Whenever they and their concerns were mentioned, it was in footnotes. Writing about the past is also a way of critiquing the present; after all we are now living out the consequences of historical events. By going back in history, we can contextualize our present more fully.

Brittle Paper

Thanks Leila! It was great chatting with you. River Spirit is a brilliant book, and I hope that readers continue to fall in love with it. All the best!

***

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions