The sun is setting again, and you are not here. Not here to capture it between your fingers and squeeze like Udara. To you, the sun is just an oversized fruit. Sweetness, warmth, and thirst. The last time I saw you there was blood on the floor, and numbness in my back. Mama had caught us kissing in my room; she said it was all for my own good. I doubt she knows what my own good is. I think she wishes she knew.

When there is nothing more to be taken from it, the vessel destroys itself.

Just like leaving an empty tomato paste tin on the floor, you either take it out or it cuts you. In this story, I am the tin—I cut myself because I am hurting, and only more hurting can stop the hurting. I have always been hurting. My mother does not know this, and she does not know that you saved me.

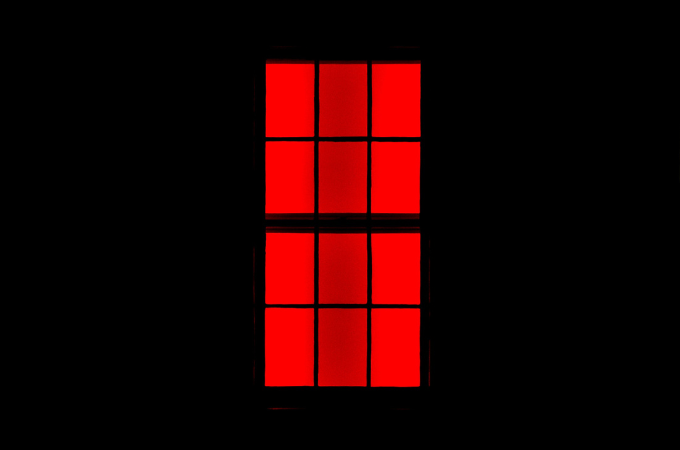

It is another Wednesday, precisely a week after she caught us kissing. I am recreating the art you have seen so many times. My mother screams; there is blood on the floor—my blood. I look at her and smile. “I thought you loved the color red?” I ask her, smirking. She only screams more. She snaps her fingers again and again, as though I were between them and she was trying to peel off my skin.

“That girl has possessed you! Dimma,” she shouts, and rushes me off to the pharmacy across the road. I am being questioned again and again like a criminal, and I have no answers for them, so I choose to block them out and focus on remembering you.

***

I met you a week after I began schooling at Nsukka, Shalewa. I thought you were the prettiest girl I had ever seen. I was climbing the brown, cumbersome staircases of the Faculty of Arts building, Block A, again and again. Because, like I always am, I was lost. I needed to submit the payment receipt for my FASA dues, and my eyes were stinging with tears. I made a mental note to surf the internet for the best ways to die because living felt like an incredible burden on my skin.

That was when I met you, and like an angel, you knew that I was lost. You knew where I was headed, and you were headed my way too. Your hair was done in black knotless braids with red curled tips, and your lips were the TikTok style: black upper lip and normal bottom lip, both violently glossed. You reminded me of the sweetness of pineapples; you smelled like pineapples. I would remember it later that night when I curled up in bed, and still searched for ways to die because I believed that angels do not appear twice, especially not to people like me.

Shalewa.

***

“Ina anụ ihem na ekwu, Chidimma? Did that girl tell you to do this? Talk to me,” my mother’s breath is in my face and inside my nostrils, like she wants to give me life again. I still do not answer her. There is nothing that can be taken out of me now. My mother thinks I am throwing a tantrum, as if for a piece of fish. She doesn’t know. “Give me that phone!” she says and grabs it from my non-existent grasp. She takes my index finger and places it on the fingerprint ID thingy. It opens. She will find your name saved with a single purple heart. Your DP is a photo we took at the top of the Abuja building last Saturday. We were smiling so hard that our lips cracked.

We haven’t talked since the incident because I do not reply to your concerned “heyyyss” and “pleeeease talk to meeeess.” I want to, but my fingers will not do so. I am not too “available” in my body these days.

My mother searches, and she finds nothing of the sort. She takes me home again. And while we walk, I still remember you. Shalewa.

***

The second time we met was at Tames Place, a unisex salon. Both our hairs were turning gold. You were dying your hair because your next hairstyle was to be golden braids. You did not want your jet black hair to destroy the whole thing. I was dying my hair because I needed to feel more in control of my life.

When we were done you took my number, and we discovered that we both lived close to each other at Hilltop. So, we walked home together silently, as the sun set in a peach dinner dress. You stopped at Favor’s Lodge, just behind the bole woman’s shop. I walked farther down to Our Lady’s Lodge. I stepped into my room and stood before the mirror. That was when Ajanaku first spoke to me.

“Too white, too white!” he thundered, and my body shook. I was harboring a hurricane in my body. I was scared, but not all that surprised. I always knew I was not the only inhabitant of my skin; it was too heavy for just me. I hardly even ate.

The most frightening thing about Ajanaku is that he does not snuff me out completely, he lets me watch while he pilots my body. So, I was there when he reached for the white-framed mirror and smashed it on the smooth milk tiles. When my neighbor came to check up on me, he connected to my bluetooth speaker and played my favorite song, Kali Uchis’s “Melting.”

Melting like a daydream, stay a while.

He increased the volume and waited until my neighbor sighed and left. He grabbed a shard of glass and asked, “You want some color, Shebi?” How about some red?” Without waiting for an answer, he slit open my palms and began rubbing them fiercely on my hair. There was no pain; it was like a dome was keeping me away from myself. “Color color color! Red is the best color for us!” he chirped like a kindergarten child with a sore throat. Ajanaku loves it red.

A notification entered my phone, and it was you. You were at my door because your room’s power had run out; you had to wait for the remainder of people sharing the prepaid meter with you to pay before you bought power again. Later, with my head between your thighs, you told me it was because you thought I looked very lonely.

You knocked and knocked, but there was no answer. Ajanaku had left me unconscious. I woke up to see my door broken and people screaming in my room. I was taken to a hospital in town in the Yahoo boy’s car. The Yahoo boy was my neighbor. Later that night, after my palms had been bandaged, you boiled some hot water and washed the blood out of my hair. You stayed with me that night, and when Ajanaku began chuckling through my lips, you only held me tighter and whispered in my ears:

I will save you.

And I loved you because you knew. You knew me and what was in me—you knew me more than my mother. Shalewa.

Ajanaku placed my lips on yours, and when he tasted a bit of your love, he grew calm for a very long time.

***

“Chidimma, you are possessed by an evil spirit. Ahhhhhhhh!” my mother announces, and begins staggering around like a drunken rabbi. There is a Bible in her hand and a piece of white chalk. She draws a holy circle and forces me inside of it. I want to tell her that the only thing that could save me was your love and your cherry lips. You are my church; you are my place of worship.

“Oh, you Beelzebub! You will perish today!” she bellows, still staggering. Ajanaku, snickers. Beelzebub is neither his name nor mine. Not even any of his close relatives. Sorry, gods are their own relatives. Like the trinity—Ajanaku is everything in one body.

“Oh, you spirit of lesbianism! Spirit of fornication! Spirit of suicide! Oh yakata yakata, fall yakata!” My mother is effervescent; she pushes me down. Ajanaku still does not answer. The gods are aware of their worth. They are proud, and their egos are like the stomach of a constipated child. Ajanaku will not answer if you do not call his name. But he decides to have a bit of fun with my mother. So, he leaves my body and catwalks around our compound. He is as tall as I am from the ground to my knees. He is slender like a woman, and his skin is striped black and white like a nylon bag. Ajanaku’s lashes are long and curled, just like mine. He stands in front of my mother and whistles,

Twinkle, twinkle, little star.

My mother jumps and screams, “It has left! Yes! Chidimma, baby, you are a star!” She hugs me so tightly that I can hardly feel it when Ajanaku takes his place in my body again. Our body. He corrects me, and I shiver. My mother bursts into praise.

“Ihe ịmere dị mma! Ihe ịmere dị mma!”

Ajanaku sighs. My body is a soaked pillow as I drift into sleep. Our body. Ajanaku lets me dream about you. Perhaps he misses you too. Shalewa.

It is midnight when I wake up with a weird kind of hunger, and the first things I see are the sleeping lizards on the wall. I sleep with three lizards in my room because our walls are cracked all the way to the outside. I have learned to sleep with them. You pretended like you had learned too, before my mother caught us kissing, and I never saw you again. Tonight, I am very angry with the lizards for being in my room, so when Ajanaku says rise, I rise and pick up my glass heels from beneath my termite-infested table.

And when Ajanaku says kill, I impale the lizards’ bellies through their backs, one by one. All three of them are on the dusty oxblood rug. I think it is all over, and I try to take my place on my bed again, but Ajanaku says eat.

It must be a joke, so I hesitate. Ajanaku says eat again. This time he is angry because gods are supposed to be doing the ignoring and the hesitating. Ajanaku kicks me in the gut, and I bend over. He picks up a lizard and puts it in my mouth. We chew. Ajanaku is not satisfied.

This is when Mother walks up on us and then decides that maybe love is love. She picks up my phone and calls you. Shalewa.

In this world, I learned that love’s beauty depends on what or who you’re loving, not even the feeling itself. I learned it from my mother. And while she calls your number, I want to tell her that it is too late. Ajanaku does not want to eat love anymore.

My mother begs me; she says you are coming to Enugu from Nsukka first thing tomorrow morning. She says, please, please. But Ajanaku’s ears are only for listening to himself. It is built in such a way that his own voice ricochets across the walls of his head. And Ajanaku only hears eat now.

My mother is asleep when Ajanaku slips out of her embrace and goes to the kitchen. He picks up the knife my mother uses to cut periwinkles’ shells so that they can be sucked out. He takes my hand, and we slip back into my room. I, too, am begging Ajanaku, please, please. But Ajanaku does not hear me.

With five swings of the knife, my mother’s head is alienated from its body. Her eyes are wide open in shock, her mouth agape with traces of spittle on her cheeks. Tears are streaming down my eyes, and it irritates Ajanaku. But he is euphoric like a schoolgirl with Capri-Sun in her hands. “Red like an apple! Red like strawberries! Red like watermelons! Red, red, red!” He picks up my mother’s head and shrieks in delight. He drops it carefully beside the remains of the lizards on the floor. He hugs her body, and her blood is all over me and us. Blood is spurting from my mother’s neck, and he tastes it, we taste it.

My mother’s blood tastes sad. Like a woman who has been patient her whole life.

Photo by the blowup on Unsplash

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions