Part I: Knowing What to Believe

In my first semester at New York University, I registered for a Critical Thinking course taught by Professor Mary Busbee. Like every college student, I spent time on Rate My Professor that summer, reading through the terrible reviews the students had left about the course and the professor. So, it wasn’t surprising that on the first day of the class, the professor declared that almost half the students would drop the course by the third class. To her, that was the tradition. We started as 20 students but by the third class, we were 12, with only 2 black female students.

As an immigrant to the United States and since I had a taste of higher education in Nigeria at the University of Ilorin, it seemed like an unnecessary privilege to only have to take 3-5 courses per semester, be able to choose a class that one likes and have the autonomy of dropping a course if one disliked it for any reason. So, regardless of the terrible feedback I read online about a course or a professor, the Nigerian in me was determined to not only stick through but learn my money’s worth and get an A+ grade out of it.

Professor Busbee taught us not to be easily swayed by available or popular information, to question things, to read fully and listen attentively for fallacies or truths, and effectively communicate our perspectives. We read and analyzed 4 books that would forever change my mindset and life:

- Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me) – by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson

- Asking the Right Questions – A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne and Stuart M. Keely

- On Bullshit by Harry G. Frankfurt

- On Truth by Harry G. Frankfurt

Simultaneously, we studied fallacies and propaganda, highlighting the impact of notable people like Martin Luther King Jr. and analyzing his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” The best part of the class was the liberty to try and share if we knew what to say, the encouragement to listen when we didn’t, the curiosity to question things, and the cautiousness to be informed so that we could understand the exchange of dialogue, ideology, and perspectives. To say my mindset never remained the same after this course is an understatement. I preserved all my course notes, often returning to them to remind myself of my biases and hindsight on critical issues.

While at NYU, I interned at several publishing companies because I was curious about the book publishing process and, more importantly, how information was made available to the world. Unlike the trade publishing companies, my final internship was at Elsevier – a leading research, science, and academic publisher. It was eye-opening to compare the book selection process for publication at Hachette Book Group or Simon and Shuster to Elsevier. At Elsevier, I was even more fascinated by the extensive process of selecting and validating researchers and data for projects like nanotechnology. I saw the layers of approval needed before research, data, or information could be released as facts that others could learn from.

With this consciousness, I finally pinpointed why I feel disgusted at assumptions, poorly stated or untrue facts, incomplete information, and generalizations. It is no longer scarce to come across a video on social media where someone with a microphone, often on a podcast, says, “We don’t talk about this enough” or “There isn’t enough information about that” or throws a generalization either in number or context like “90% of men do ABC…” or “Africans are XYZ…” to make their point sound true, essential, and urgent.

Notably, the dependency of mass action on leading opinions by a few people scares me. It scares me how until the leading voices of certain movements say or do something new or provoking, some people don’t often think for themselves or engage with the topic and issues independently. Even with that, the urgencies of such moments force many to participate in unrealistic and non-lasting solutions to repeating problems.

One skill I learned from Professor Busbee’s Critical Thinking course was the art of patience in the face of propaganda and how time truly tells. Notice how these conversations, like a tidal rise and falls, move water to the shore and then pull back. Many make statements and then retreat to the comfort of their homes until something else regarding that topic happens. Professor Busbee helped us realize that we must not jump on every popular bandwagon. With this cautiousness, I learned that the loudest, most heard, or influential voices aren’t always the wisest or most informed ones to drive the action necessary for a sustainable change that benefits the people with the most urgent needs.

Most importantly, I re-learned what I assumed we already knew; Google searches, content creators, podcasts, tweets by famous people, quotes, op-eds, personal experiences, nonfiction, and our feelings about history do not qualify as research, facts, or truth. Especially interning at Elsevier, I began to have a different level of intellectual respect for people who did peer-reviewed and published research on various life and world-changing topics.

In conversing with other classmates, I gained more confidence in saying I can listen and hear you out respectfully, but I am not obligated to agree, believe, accept, or fight for other people’s causes, perspectives, and convictions, especially when there is too much evidence to prove a lack of complete truth or fact. Notably, some are convicted about the wrong things or, sometimes, the right things but misuse their passion and platforms in the wrong ways. For some, the loudness of their convictions is often confused for its truth and this society of tolerance, participation, and acceptance we encourage dangerously equips and spreads their misinformation or misguided actions.

By the third week of the class, when we started forming discussion groups, my longing for safety in familiarity and likeness almost convinced me that I must be in the same group as the other black female student simply because I saw the Asian students form one group and the white students form another. However, I consciously refused that notion. Like this class and our groups, facing what’s new, unknown, unfamiliar, and potentially disagreeable is scary. By the end of that semester and even now, I could only imagine how much more terrifying it would be to live in a world with this much information and accessibility but very little knowledge, understanding, and wisdom to share and apply in a right, ethical, and justifiable way.

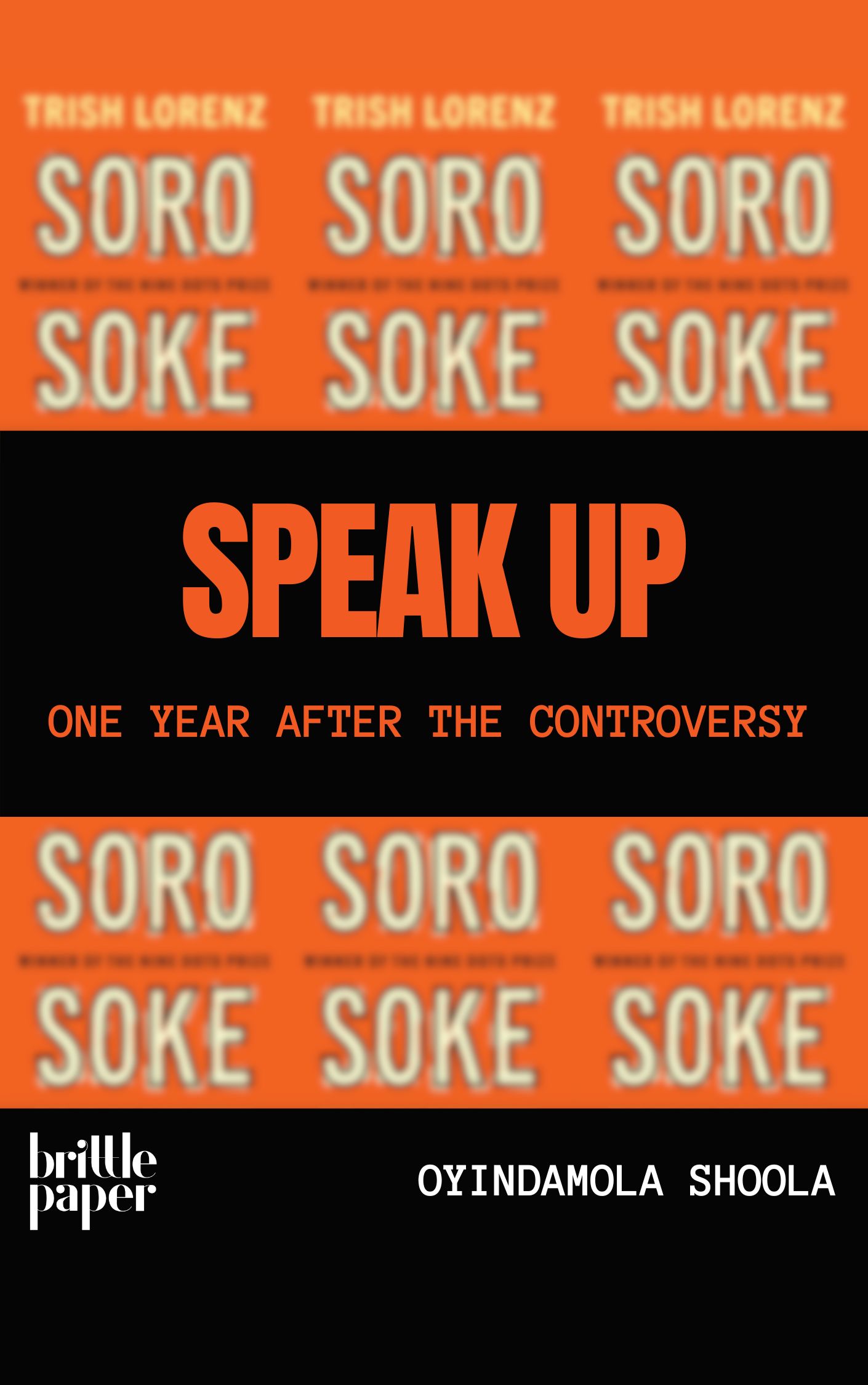

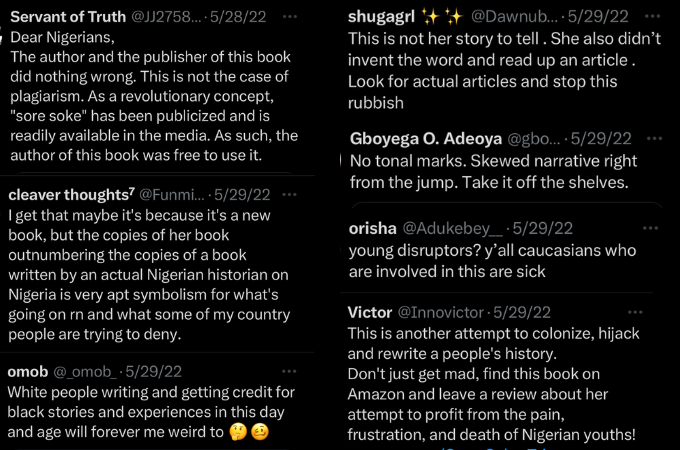

Information itself lacks power without application. The more I am conscious of the power of being informed and conviction of belief, either shared by speaking or writing, the more fearful I am of its misuse and misunderstanding. Seeing how cruel and unforgiving our world can be, especially on the internet, makes me even more anxious about being a voice of or for anything in this world. This series continues with my review of Soro Soke and a realignment of several mistruths that circulated the book and its author, Trish Lorenz.

Be sure to check back in next Friday for Part II

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions