For several decades, the issue of wars, child soldiers and other gory dysfunctions became such a staple of African literature that the pejorative poverty porn was born.

There are occasional hiccups, but African literature seems to have survived the stereotyping and seems to be coming of its own; indeed African literature is enjoying a renaissance as young writers insert their unique voices into the literary canvas and share stories that together paint more nuanced and robust narratives. It is a good thing.

Several years ago, I read Ishmael Beah’s A Long Way Gone, a gripping memoir about his life as a boy soldier during the civil war that engulfed Sierra Leone in the nineties (see Uche Peter Umez’s insightful review here). A bestseller (over 700,000 copies sold), it became mired in controversy as allegations surfaced that much of it was probably made up by Beah. The controversy did irreversible damage to Beah’s book; it should perhaps have been listed under the genre of fiction to avoid the needless uproar about its fiction. Regardless, it raised profound questions about the fate of children born into wars they did not ask for – and made to fight their way out of them.

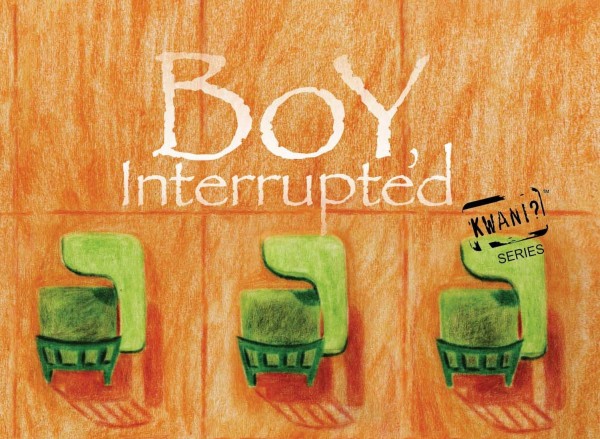

There is good news. Saah Millimono’s book, Boy Interrupted, tells Ishmael Beah’s story, this time as fiction. It might as well have been a memoir; in many parts it is so real the reader’s emotions run riot.

Boy Interrupted takes place, not in Beah’s Sierra Leone, but in Liberia, between 1989 and 2004. Tarnue, the main protagonist and narrator, is a ten-year old boy doted upon by his gentle parents. He walks around familiar and comforting surroundings, eyes and mind open, full of wonder and awe as the world colors the streets of his childhood, as if with crayons. His parents soon decide to interrupt his idyllic life and apprentice him to his uncle and his wife, far away from home in order to expose him to better opportunities in education. The separation from home is a painful dislocation from all that is loving and familiar. The uncle’s wife is mean and abusive. Tarnue becomes a child laborer, selling foodstuff on the streets. It is a roller-coaster from here on, and the reader soon gets trapped in the pages of this little book. I have to say Millimono draws terrifying pictures with words. It is autobiographical, but in a good way:

Once we got into the room, my uncle’s wife told me to take off my clothes. Wringing my hands and trembling, I did so. And then she began to beat me. Again and again the rattan whistled into the air and came down on my head, my back, my belly, my chest, my thighs, my feet, my legs, my hands. My screams filled the house. At one point I tried to open the door and run outside, but I was grabbed by the throat and dashed to the ground. I writhed on the floor and took the blows. I thought I would die.” (p 13)

This book is about a little boy who ends up as a boy soldier called Rebel Baby, but then it is a lot more than that. It goes beyond war. It is a love story and the heartaches that dislocation births. It is also about class and class warfare, one which hearkens to Chibundu Onuzo’s book, The Spider King’s Daughter. A good book should remind the reminder of wondrous things. Boy Interrupted is a good book. It reminded me of the books of my childhood. I remembered the haunting sadness I felt when I read Camara Laye’s The African Child; Millimono does an excellent job of getting in character as a child. I remembered Chukwuemeka Ike’s lovely book, The Potter’s Wheel, and I thought about the conventional definition of war and how there are many forms of war and the resilience of children in Africa who still manage to carve out a living, some loving and every now and then heart-rending joy in between the spaces of the places that are their daily theaters of war.

Tarnue endures savage physical and emotional abuse but is rescued from this and given a respite when he befriends Kou, a little girl from the wealthy side of the street. The result is a tender love story between the protagonist (of peasant stock) and the girl Kou (of upper middleclass upbringing). I remembered Ngugi Wa Thiong’o’s Weep Not Child as I thought of childhood love and the characters Mwihaki and Njoroge in the time of the Mau Mau. Things are going well but just when it appears Tarnue has caught a lucky break, war breaks out in Liberia and things fall apart in the most heartbreaking of ways. The book smells of death, but it also smells of innocence, of raw honesty. This is not poverty porn. This is in many ways a love story. And Millimono is no slouch when it comes to words, you read the phrase, “The rain fell in sheets…” and you remember it is always in your head when the rains come crashing down in mean sheets. All through the hell that is war, life goes on and Millimono celebrates Liberia’s culture robustly—in her food, in the language and in the dogged insistence of her people to live and love, in war and in peace.

Millimono’s little book made me think about history. History as a core subject is being chased out of the classrooms of Africa by those—mostly misbehaving rulers—who would like Africans to forget. Boy Interrupted is an authentic history book because in between the pages of fiction there are all these spaces filled with historical allusions that are easily googled and confirmed. In this book real life people are characters in well-researched passages: The late president Samuel Doe, gruesomely murdered by Charles Taylor, the current president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. We learn about the West African peace-keeping force, ECOMOG. There is ethnic cleansing; learn about the St. Peter’s Lutheran Church massacre in the summer of 1990. And there are still living witnesses like the legendary BBC journalist Elizabeth Blunt who was a correspondent in Liberia at the time. Watch her testimony on the death of Samuel Doe. Read this about the death of Samuel Doe. She is on Twitter as @bluntspeaking. Follow her, and ask her about Charles Taylor’s Liberia, LOL.

Boy Interrupted is a delicate, intricate story told beautifully and well edited too. As a lovely aside, hats off to Kwani Trust for publishing a book whose quality can rival any out there in the world. I could not find a single word out of place. There were no grammatical challenges to taunt my rage and the book’s design was a tasteful ode to artistry. I was impressed. Sadly, it is almost impossible to find this book to purchase anywhere. It is definitely not on Amazon or anywhere near the usual places where books should be found and purchased. Kwani needs to be a lot more aggressive and innovative in marketing its products. Still, I love Kwani Trust. It is the face of what publishing should look like in Africa. They are working with a business model that currently involves only (okay, mostly) Western donors. I believe that these initiatives should be an expense and that public institutions in Africa should play their part. There is a good history of Kwani Trust here. Filmmaker Wanjiru Kinyanjui, sculptor Irene Wanjiru, Ali Zaidi and the writer Binyavanga Wainaina are mentioned as part of the dreamers and doers that birthed the resource. I salute their industry, passion and vision. We should all rise and support them. They are doing exactly what we have been dreaming of doing.

Boy Interrupted is a complex narrative. There is mystery. Tarnue’s parents are perpetually in the distant background—these shrouds in the distance, timid souls stripped of dignity by poverty. There is education. This book is an important chronicle on the academic sorting that takes place in West African schools, where for many children, classrooms are places of terror where those with the “wrong” form of intelligence are derided, berated and beaten black and blue. There is humor, albeit mostly dark:

We Liberians na love our own country,’ Patience said, ‘and we na love each other.’

‘You have said it all in a few words, Patience,’ Garmai said. ‘This is the same reason we are still living in huts, still living in darkness, and can’t still produce our own food because we too selfish.

‘And the worst of it all is that most of our so-called book people don’t know nothing,’ Garmai went on. ‘While the Lebanese and Indians are every day on their feet making money, they sit in their offices running chi-chi-poly, envying one another, and loving to their workmates. And then in the evening they go drink Club beer and talk nonsense.’ (p 39)

There is a good piece about Saah Millimono here. Millimono was born in 1981; one wonders what he saw growing up. His book (the second place winner of the Kwani? Manuscript Project Prize) comes across as honest and heartfelt. It is not the contrived pabulum of Uzodinma Iweala’s Beasts of No Nation, strutting all over the place with that horrid contraption pretending to be a version of pidgin English.

It is not a perfect book. The dialogue is uneven, at some point the violence numbs the senses, and it becomes mechanical; bleached human skulls everywhere, death and all the clichés of war are solemnly gathered here for a pity party. It is about the smells of war and death warmed over. A boy goes to war becomes a boy soldier, earns his street cred by drinking, using hard drugs and killing on orders. He survives all of this and ends up marrying his childhood love who is pregnant for a warlord at age fourteen and is caring for a late friend’s set of twins. Do they live happily after? We don’t know. The book clatters to a flustered end right there. There may be a sequel or a movie. White folks love these kinds of scripts. It’s all good. There is a Nigerian soldier named Okonkwo with tribal marks. That seems improbable. But I like this book, I forgive Millimono, for he wrote from his heart and delivered a good story.

*******

About the Author:

Ikhide R. Ikheloa or Pa Ikhide as he is called on social media is a blogger, popular or notorious for his social and literary commentaries. He has strong views about African literature and he shares them freely. He writes non-stop on various online media. In addition to blogging at www.xokigbo.com. He has written for several Nigerian online newspapers and literary journals. He refuses to write a book because he stubbornly insists that the book is dying a long slow death.

Ikhide R. Ikheloa or Pa Ikhide as he is called on social media is a blogger, popular or notorious for his social and literary commentaries. He has strong views about African literature and he shares them freely. He writes non-stop on various online media. In addition to blogging at www.xokigbo.com. He has written for several Nigerian online newspapers and literary journals. He refuses to write a book because he stubbornly insists that the book is dying a long slow death.

Ainehi Edoro January 08, 2018 16:00

hi Scott, Check out Magunga's online bookstore based in Nairobi. They have the book in stock and may be able to ship one off to you. Follow this link: http://www.books.magunga.com/store/boy-interrupted-boy-interrupted-by-saah-millimono/ Good luck.