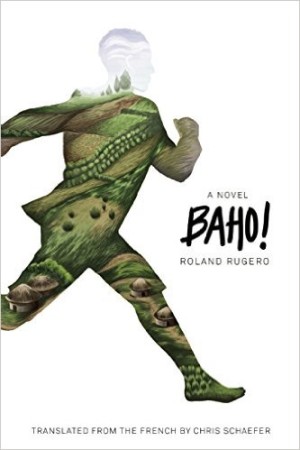

A couple of weeks ago, the English translation of Roland Rugero‘s second novel hit the stands, making Rugero the latest in a growing body of foreign language African novelists gaining access to a global English-speaking community of readers.

Baho! is the story of Nyamugari, a mute adolescent boy falsely accused of rape. The premise of the story—the idea of a mute person attempting to testify to his innocence—is fascinating. The writing is also rather compelling as is evident in the short sampler below.

The novel is set in rural Burundi. And somehow the rural location of the story gives the writing a beautifully pastoral texture. In the excerpt below, a series of violent moments are powerfully conveyed against the backdrop of a pastoral canvas of slopes, hills, sheep herding, brooks and so on.

Congrats to Rugero for finally getting his work out to an English speaking audience. Rugero who was born in Burundi in 1986 is a journalist and filmmaker. Baho! is his second novel. It was translated into English by Christopher Schaefer and published by Phoneme Media, the same guys who introduced Inongo-vi-Makomè’s spanish novel, Natives, to English-speaking readers [read here if you missed it.]

This has truly been the year of translated African fiction, with Fiston Mujila’s break out success. Mujila’s Tram 83 was published by a small indie press and went on to win the Etisalat Prize for African Literature, in addition to snagging a spot on the International Booker Prize shortlist.

Rugero’s Baho! —the first Burundian novel to be translated into English—just might be the next Tram 83 so make sure to read it sooner than later.

Enjoy the excerpt below courtesy of LitHub

Click here to order.

***

Uw’ivyago vyagiye n’ivyatsi ntibimubisira

Uw’ivyago vyagiye n’ivyatsi ntibimubisira

When tragedy assails you,

even the plants along the footpath impede your way

Nyamuragi runs quickly. He knows this hill and its slopes. Every evening he walks along them, pleased to survey his own small domain. The land of his fathers. It was many years ago that he was born here. A boy, the son of a man and woman who lived further upstream along this little brook where he washed his face this morning. He sees flashes of his life parade past, details of moments when his parents were still alive, like that evening when he cut his calf with a sickle while trying to throw it at a stubborn lamb.

When he saw blood flowing that evening, he contemplated the sacredness that resides in every animal. He thinks of intama, the sheep. White and peaceful. God himself wouldn’t know how to dress as white nor be as peaceful. A strange animal that rarely lifts its head. The ram has a husky, fitful voice and a perpetually drooping head. The elders were not wrong; it is an animal to fear.

He had a large family. In his boyhood they were seven: his two parents, himself, three lambs, and a ram. Nyamuragi would take the flock to pasture all by himself, a task he did not relish. He wanted animals that brought him to life with cries of confusion and attempted to escape from his watchful eye! Not these studious miscreants, honest to a fault, calmly looking for grass in the wood, and then plodding back to the rugo in perfect obedience. With them everything was so predictable! He would have preferred a rebellious goat—intractable, with a black back that he could lash with a young rod. In the end, the mute did not learn how to be a shepherd. No, he became a thinker.

His parents would go to the fields in the morning, and Nyamuragi would lead his sheep out. Surrounded by those peaceful companions, he reveled in a silence that was playful above all else. Slowly taking the sheep to pasture became a delightful habit for the little boy. It allowed him to be a man. He learned to observe, to listen, to be patient and, meek as a lamb, to share the warm fur of his beasts when evening visited the family abode. There was a true camaraderie. Occasionally he would even steal corn sheaves to give them. But life with those beasts was painfully predictable!

When he was nine, accompanied only by his sheep, he began to observe men walking their fields. Perpetually at his side, the animals were angry at him because he wanted more sheep. But his parents were not very rich. They didn’t have more than the four sheep to give him. Each time he watched his old neighbors passing by from his perch, he thought about Hop-o’-My-Thumb, the small, clever, youngest one who meandered along, tossing out white pebbles the length of his route. They were small beings making their way along paths of ochre earth, on well-trodden bare soil that was dense, naked, and slippery when rain decided to visit. Each one walking by. Miniatures, he observed them from on high. All of which discouraged him from speaking.

Then, when he was 14, his parents died; murdered in a din of harrowing screams! He remembered his mother’s terror, her dying curses, the blood that had run, soaking their small home’s entryway mats. Red, then black. A sickening odor. His father, who had resisted, had managed but one small blow—a pestle strike—on the neck of one of the killers. The jumbled goodbye shouts… Nyamuragi had hidden himself far away in the depths of his parents’ bedroom, and the monsters had not bothered to check the back of that unfortunate house. They had intended, of course, to make off with his sheep. Their lives were worth as much as his parents’—war had reached a fever pitch. All of which made him decidedly unwilling to speak.

While she was alive, his mother had taken him back to consult with the healer, the mupfumu, in order to determine once and for all the source of his muteness. The healer was new in the area, a specialist of very high caliber whose opinion was prized. The wise man had determined that it was a serious case: the child brought to him had the ikirimi, an unfortunate sickness that blocked the tongue and kept Nyamuragi from speaking.Ururimi, the tongue. The healer prescribed surgery for Nyamuragi. Rummaging around in his throat, he cut a few small veins and then administered some bitter leaves to be gargled each morning. The little boy bled. And then he became truly mute. He would have preferred to tell his mother that in the beginning he simply did not want to speak, but the good woman would not have understood. She considered him some sort of victim. Which was knowingly confirmed by the healer. He required a cure, and the prescribed cure had been carefully administered. In the end, it precluded any possibility of ever speaking again.

With the death of his parents whirring in his ears, Nyamuragi withdrew all trust from the words of men. He told himself that nothing remained but to examine their deeds. One night he fell asleep to the noise of his mother’s feet, the trembling voice of his father and his paternal breath reeking of alcohol, and the next he fell asleep to the freezing echo of their death and the morbid aroma of their decomposing bodies!

From this state of affairs, he had deduced one thing: Man is all-powerful. He is to be feared. And fear, at its root, is but an unspoken questioning.

He had made a vow to hold his tongue. He enclosed himself in a silence as thick as the wool of his sheep and his big-headed ram. Since then he had despised words. He believed in gestures and things. It wasn’t from some long and grandiose pronouncement that his parents had died, but from machetes and hate, from the lethal blow of an axe. Because of this, he had been uprooted. The growing tree, the axe that lays it low… deadly things.

So that is the story of Nyamuragi, the man who was running and jumping, dodging and sweating in Kanya’s fresh morning air, all while he pondered how best to demonstrate his innocence.

* * * *

The huge misfortune, as he understood it, was to show up at the creek, when he never usually went over to that side in the morning. And if he dared to stop, they would capture him, because he is now a freak of nature.

A freak of nature. Little Hop-o’-My-Thumb. His mother… Nyamuragi stops in dismay! He turns towards his pursuers. The mute finally understands: with the hills so completely mobilized, he cannot go on running indefinitely. What’s more, since he cannot learn to speak in these few minutes on the run, it is better to just turn himself in. He will try to defend himself with gestures, as he has always done until now.

Suddenly, he is knocked over and seized by the collar. The gnarled stick of an avocado tree breaks against his sweaty back. It hurts. He begins to cry. The pain of misunderstanding. He tries to disentangle himself from the hands clasping his forearms. He flails. He wants to explain himself. But in a squirming that reads like a new attempt to flee, there seems to be only one response. A vigorous hoe handle to the head. Swung by a woman. He has the time to see her raise the handle, the image of his father… But he faints before the blow can even reach him!

* * * *

Nyamuragi is dragged up the hill. Cries gush forth. The people will carry out the sentence! No court hearing is to be held, but what else is to be done? The deeds are too serious. “Uproot the evil from among your children!” the heart of Kanya thunders.

Felicia Reevers May 02, 2016 09:58

Many thanks, Roland! The excerpt was captivating. Looking forward to reading the book.