#StoriesToLiveBy

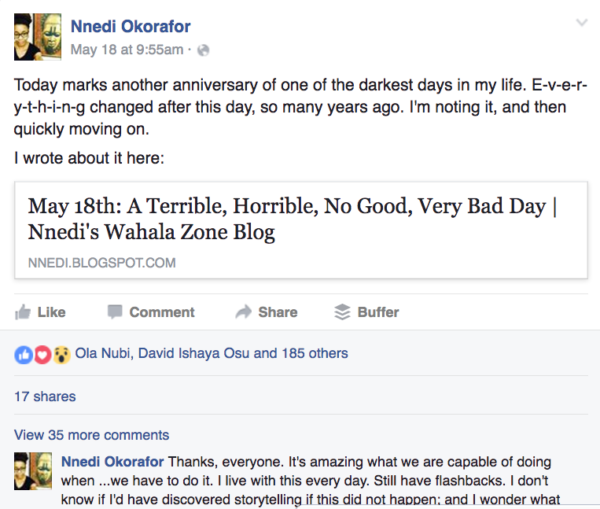

We are still reeling from reading this amazing story about triumph in the face of insurmountable odds. 7 years ago, Nnedi Okorafor shared a story on her blog detailing the life-changing experience that brought her to the gift of writing.

Last week Wednesday marked yet another anniversary of this dark and difficult moment in the author’s life. She talked about it on Facebook and, as is to be expected, received an outpouring of love from fans.

This true life experience narrated by one of Africa’s most hard-working and beloved writers is a must-read.

Whether you are an aspiring writer hustling hard to make it or you are simply up against obstacles that make your goals seem unreachable, Okorafor’s story will give you clarity of mind and inspire you to rethink your strategies for success.

Thanks to Okorafor for sharing this with her fans. We found it inspiring and hope you do the same.

[The story was originally published in Africana.com (now Blackvoices.com)]

***

Legs By Nnedi Okorafor

Long and lean, they once moved me quickly about the tennis court at high speeds. They kicked boys in grade school that called me “nigger.” They’re what most men first noticed about me. They are often the source of ridicule. And they are where I have my four tattoos. Nevertheless, these same legs were also the source of the darkest time of my life. And it was my mind which rests somewhere above these legs that carried me to where I am today.

From the age of nine to the summer after my freshman year in college, I spent most of my free time playing tennis. The product of two athletic parents, it was no surprise that I was blessed with their gifts of coordination, speed, and motion. My long legs made me fast and my long arms could blast tennis balls into orbit. My serve was clocked at one hundred fourteen miles an hour. For most of those years I played competitively, traveling around the country to compete in national tournaments with the likes of Lindsay Davenport, Jennifer Capriati and Chanda Rubin.

My senior year in high school I took a break from tennis to join the track team. That spring, I won 22 medals in the 400-meter dash, the mile relay, the high jump and the long jump. But when I got to the University of Illinois, I chose to join the tennis team. Aside from the tennis courts, my long legs took me around a very large campus. All was going well; little did I know that it was all about to change. One can never fully anticipate when something is going to knock her legs from under her.

Through most of my sports days, I had scoliosis, the curvature of the spine. It was genetic. All three of my siblings also had it to some degree but mine was the most serious. From the age of thirteen, my spine had been shaping itself into an “S.” I wasn’t in pain and I looked fairly normal (people just thought I had bad posture). When my doctor told me that if I didn’t have a spinal fusion performed, I’d be severely bent over with crushed internal organs by the age of 25, I wasn’t worried.

“A lot of people have this surgery,” the doctor said. “Even athletes. You’ll be back on the tennis court in 2 weeks.”

The only risk was a one percent chance of paralysis. When I weighed that one percent against a 100 percent chance of being bent over, freakish, lungs and heart squeezed terribly, the choice was obvious. So the summer after my freshman year in college, I walked into the hospital for the surgery. I was in peak physical condition and had few worries.

Ten hours later, I woke up in a hospital bed and fluorescent pink and green praying mantises were hopping around the room and a big black crow was trying to throw its body through my hospital room window. I was so drugged up with morphine and in so much pain that I didn’t notice my parents, sister and my best friend, James, standing there. It took me a full day to realize that my legs were dead. I was completely paralyzed from the waist down. I was a victim of that one percent chance.

I later learned that my doctor lost a lot of sleep those next few days. Just recently, almost a decade after this happened, my doctor said for the millionth time: “I just don’t know what happened.” There was nothing wrong with my legs; he thinks it was the spinal cord that was damaged during the procedure. Those first few days, he wasn’t even sure if I’d ever walk again. My condition was so unusual that at one point my doctor asked if I minded being included in a medical book (“Sure,” I said). A group of doctors even invaded my room to get a look at “such a rarity.” My mother took it the worst. I distinctly remember how her usually perfect Afro being lopsided when she came to see me. My father, a cardiovascular surgeon, took it in stride, focusing on dealing with the problem.

The first two weeks, I was a mess. When you can’t walk, you have to learn to depend on others. To someone who was very vibrant before, this was humiliating. I had to be carried every time I wanted to use the bathroom, take a bath, even to just turn on my side to get more comfortable. And more than once, no nurse answered my call. I watched my skinny but strong legs waste away to sticks. I grew paranoid of fires in the hospital. Since I couldn’t move, I imagined that I’d have to watch myself burn to death.

A horrible stench seemed to waft from the walls next to my bed and I got into the habit of spraying them with perfume. It was in that stinking sad hospital room that I first started to write, documenting my fears and fantasies.

Writing kept me sane.

After the first week, some of the sensation began to return. I wouldn’t be able to move my toe, then the next day I would. Then the next day I could move it with less effort. The second week, I started physical therapy. Don’t believe what you see on TV — nobody just suddenly finds that he or she can stand up. It’s a long, scary, difficult process that requires intense effort every time.

Imagine not being able to feel your legs. When you close your eyes, they disappear, too. Now try hoisting yourself up on those dead sticks when your back has recently been sliced open. “One fall,” you’ll keep thinking, as you sweat profusely from the effort. But if you don’t try, the less likely you’ll ever walk at all. Again, I had to go with better odds.

I got through physical therapy by focusing not on the results but on the doing. The workout. And I also learned the art of compensation. When I couldn’t do something, I’d find a way to replace that something with an equal but different substitute. For example, I replaced competing on the tennis court with competing with my paralysis. And I was going to win.

I returned home, using a walker. The sensation in my legs was slowly returning, and the physical therapy was regenerating my muscles. Some weeks later, I graduated to a tri-pod walker, sort of a half-walker. By the time I returned to my university, I was using a cane. It was hard because people kept asking me what had happened. Everyone knew me as an athlete and there was no visible sign that anything was wrong with me. I didn’t limp, I’d gained my muscles back. You see, I didn’t need the cane because my legs were weak; I needed it for balance; like a third leg. I walked very slowly and carefully. Some people even thought my cane was just a fashion statement.

Eventually, I stopped using the cane, though my balance remained at about 85 percent. I wasn’t able to return to the tennis courts because I could no longer move quickly. My legs were strong but the nerve damage made it hard to get them to obey my commands. I continued to compensate. Where I couldn’t compete, I went to the gym. When I couldn’t feel my feet that well when I drove, I started driving with a flashlight, to illuminate the pedals and confirm where my feet were when I needed to. Since I can easily be knocked down due to my not-so-great balance, well, you don’t see me near any mosh pits at concerts.

I also changed my major from pre-med to English. Through that horrible experience I discovered that I had a talent for writing. Everything happens for a reason, I believe. And some of the most horrible things are lessons in disguise.

Once in a while, I look at these legs and wonder what I’d have been doing if this didn’t happen to me. But then I simply fold them underneath my desk and continue writing.

Epilogue

Rocks You Like a Hurricane

This song by the metal band called the Scorpions was the soundtrack to one of my worst morphine hallucinations while I was in the hospital. It involved tennis courts, wet hair, praying mantises and pink large beetles. I don’t know why my brain chose this song. I never particularly liked it.

See/hear it here.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions