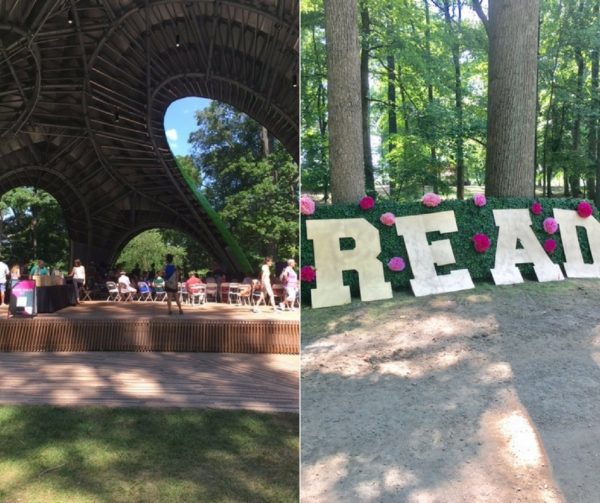

The city of Columbia, Maryland—a city located midway between Washington D.C. and Baltimore—hosted its first literary festival ‘Books in Bloom’ this past Sunday on June 11 at Symphony Woods Park. Nigerian writer and Columbia resident, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, headlined the event this past Sunday promoting her book Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions.

Downtown Columbia Partnership hosted the festival in cooperation with Howard County Library as one of the events celebrating the city’s 50 anniversary.

Before reading to a packed crowd, Adichie said:

“I am not a feminist because I’ve read the right books. I am feminist because I observe the world. I’m a feminist because since I was old enough to think, I observed that the world didn’t extend the same courtesies to women as it did to men. So my feminism is rooted in lived experience. So I thought this book was that and it has a practical use.”

On Feminism and Culture

Adichie read the fifteenth suggestion from her book:

“Teach her about difference. Make difference ordinary. Make difference normal. Teach her not to attach value to difference. And the reason for this is not to be fair or to be nice, but merely to be human and practical. Because difference is the reality of the world. Because by teaching her about difference, you are equipping her to survive in a diverse world.”

When an American-born daughter of Ethiopian immigrants asked the author about how best to talk to her traditional Ethiopian parents about feminism, Adichie stressed the use of anecdotes instead of jargon.

“It may be helpful not to use the word ‘feminism’ but use examples instead when talking to family and bring it to the level of storytelling. Sometimes theories are too abstract, that is why in this book, I did not use too much feminist jargon such as ‘patriarchy’ and ‘misogyny’ and sometimes people don’t know what you’re talking about but if you say to them, “Hillary Clinton does one thing and Mitt Romney does the same thing but who is judged more harshly and is that fair?” And you know what, the person may say, ‘I know what you’re saying’. If you look back into Ethiopian history, you’ll find those women. Sometimes it’s useful to pull from history.”

Feminism isn’t an American invention

Adichie asserted that feminism isn’t an American invention, challenging the audience to look for narratives of resilient women throughout world history.

“Sometimes Americans think it is but there have been throughout history feminist women in all parts of the world. They may not use the word ‘feminism’ but they do stand for those values.”

The author said she likes to talk about her great-grandmother who was labeled both ‘headstrong’ and ‘troublesome’ to talk to family members who would otherwise not be open to the idea or the language of feminism.

“Of course, she didn’t know the word ‘feminist’. She refused to allow people—men—to take from her what was hers. When her husband died young, she couldn’t inherit the property because it was supposed to be for her husband’s brothers and she said ‘no’, it’s mine. So she had this label of ‘headstrong’ her entire life but she stood up for her rights and I like to talk about her because it’s a way of disarming them. So if they say, ‘You’ve read too many American books about feminism’, I say, ‘Okay, let’s talk about my great-grandmother,’ and suddenly they don’t have that reflexive resistance at all. It’s important to fight these battles now so that our sons and daughters don’t have to fight them.”

Feminism by any other word is not feminism

When asked by a female audience member, ‘Why is feminism always directed to women? Until we make this a non-gender issue, it’s never going to become mainstream, so can we think about ‘humanism’ or another term for this?’ Adichie simply replied ‘no’.

“I’ll tell you why. My vision of feminism is not directed only to women and I don’t think it’s possible to talk about gender equality and not include men—we share the world with men. I think calling it words like ‘humanism’ or whatever, there’s something about it that seems to me a kind of hiding because the problem with it is that its women who have been excluded, its women who have been oppressed, it’s women who have been suffered all of these negative consequences, and somehow to call it ‘humanism’ seems to be hiding away from naming what the problem is. I take the view that unless we give things names, then we can deal with them. Humanism seems a bit too watery. The thing for half of the world is that, for so long, there’s been oppression, exclusion and if we want to fix that, we have to name it honestly—part of the problem is to get men on board, we have to make them feel comfortable. Why is it always about making men feel comfortable? There are many men have taken on the feminism label and are proudly ‘feminist’. I know many men who are. I don’t believe in the need to find a new name. I do believe in the need to make it mainstream and make it relatable. This is related to what I was saying about [feminist] jargon, if maybe we are talking about feminism, we use the level of story or example, rather than using jargon.”

On Raising Little Boys and Girls

“I think raising boys differently is as important as raising girls differently. It seems to me that we borrow some of the things we apply raising girls to raising boys. Parents are not as quick to offer comfort to a boy who trips because the assumption is that we need to toughen the boy up. And I have also known progressive couples who have expressed they are embarrassed with their little boys crying too much or being ‘soft’. I think in general, what I am saying is that I think we need to re-define masculinity—and part of the problem is what we’ve decided what masculinity means. I think we need to teach little boys that vulnerable is a beautiful and human thing and this idea of being strong doesn’t make sense because what it does is to teach boys and men to hide—what we’ve done is create these layers that men hide behind. So that idea that if you’re a man, you can’t cry but they are crying on the inside and if they aren’t able to cry outward, it comes out as violence or aggression—it’s important to teach them about vulnerability, how to express themselves and to praise them for doing that. Part of my feminist vision is not one where we talk only about mothers and caregiving but also about fathers and caregiving—which is so important. I think if little boys see alternatives to this toxic masculinity, they will see that they don’t have to be that. When there’s talk about parenting, it’s always talk about mothers—we need to talk more about fathers. We need to make it more ordinary—part of it is not overpraising men for raising their children. It’s very worrying to me when someone says, ‘He changes diapers, that’s great.’ No, it’s not great, it’s just normal.”

Advice for Writers: Rejection is part of the Process

The Nigerian author said that writing is the love of her life—but writing and making the decision to get published are entirely two different things—and a part of writing is rejection.

“Writing is the thing that I love, the thing that makes me happiest. But making the decision to be published was something a bit more strategic and I did my research on how to get published. I learned to try to get my short stories published and started getting rejection after rejection after rejection and I kept sending and sending and sending and finally someone said, ‘Not bad, you might just publish this.’ That’s how it started, which is to say that rejection is part of the territory. You have to care about writing. It has to matter to you in a way that it is visceral and true. I would stay up until 2 or 3 in the morning, I would write because I had school during the day and I had other responsibilities. Because writing mattered so much to me, I would take out time from my sleep really to write. And I think in the end, that’s what matters. You have to care and if you care, I think it will work out for you.”

*********

Brittle Paper thanks Arao Ameny for this detailed coverage of Adichie’s talk.

*********

About the Author:

Arao Ameny is a Ugandan-born MFA Fiction student at the University of Baltimore and resides in Columbia, Maryland. She’s obsessed with Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera. Find out what she’s reading on Twitter at @africanwriter or Instagram at africanwriter.

Arao Ameny is a Ugandan-born MFA Fiction student at the University of Baltimore and resides in Columbia, Maryland. She’s obsessed with Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera. Find out what she’s reading on Twitter at @africanwriter or Instagram at africanwriter.

Simeon Mpamugoh June 20, 2017 10:58

Well simplified response from Adichie such that the topic: Femininity is better understood. Women must stand up for what they believe. There is no difference between a man and woman except in what they have between the thighs.