“Nobody will ever get my milk no more except my own children. I never had to give it to nobody else—and the one time I did it was took from me—they held me down and took it. Milk that belonged to my baby . . . . I know what it is to be without the milk that belongs to you; to have to fight and holler for it, and to have so little left.”

– Toni Morrison, Beloved.

IT IS PROBABLY an Armageddon Summer, somewhere, when Rosa Caramella is frozen into time. Rosa Caramella is my favourite cow. Named after Mia Couto’s hunchback outcast in Every Man Is a Race, little is known of her, only that she is a woman, cow, with the desperate need to love despite her mounting sadness. I have only met her through this one picture where she sits in the still like a God. Posing. Notice there is slight smirk that plays on her lips, or is it a pout? Look at those refined curling toenails, the certainty of her brown coat, her slender figure. Rosa here, date unknown, is not a fully fledged cow, but we, you and I, can see that she has all the makings of a great cow. Rosa will be beautiful. Rosa certainly knows this too—watch how those hazel brown eyes stare carefully at the camera, enticing—somewhat, a childlike innocence, careful, carefree, know it all, unflinching, brown, Rosa. I have wanted to write about Rosa since the day I met her, on Google sometime in 2015, yet the only approach I could think of was, well, the holy cow approach, and that was useless because the more I looked at her the more I knew that she was, is, not holy, or rather, not always holy, is not just holy. Long sentence, I know. I was unlanguaged until I read Megan Ross’ Milk Fever, and now that I have read it, I can say, Rosa:

your milk comes apart so it can be held

like soft frangipanis inking your skin

(Milk Fever, 16).

Reading Megan Ross’ Milk Fever has been like delving into an ocean, of blood. The veins are rivers, heavy breasts pelt bullets, thick lips shun prayer, and the madness of cows and women alike bursts upward like the wild dandelion flower. Milk Fever helped me reconcile with the historicity as well the spiritual connections between women and cows—something Toni Morrison in Beloved incites as well. Beloved is, I would suggest to those interested in the delights and pains of cows and women, a companion text to Ross’ debut collection. Set in the aftermath of the American Civil War Beloved is not only the story of a baby ghost but also a comment on the intricate assemblies women share with cows: Sethe, the protagonist, struggles incessantly with the incident of her milk being taken from her by the descendants of slave owners. They took her milk. Those who do not even know what it is that makes milk.

In Milk Fever, the planets and the ocean’s floor come together—death samples blood through the feminine whose present future blooms in the afterlife of motherhood and wet wounds. Butterflies change shape, breasts swell, teeth clatter, and the vagina envelopes the whole of human history in a gulp. It is a holy reminder to many of us that someone else is always bleeding “in the shop of horrors” (21).

When I was a little girl I was a false prophet, my eyes were crystal balls and through them I saw the many demons, then dreams, of lovers and children and pink cotton and everything else we are taught to dream off. We were all false prophets, the girls in my neighbourhood and I, we hissed secrets and exchanged our dreams and “from their mouths a small library blooms, an encyclopaedia of stems and ears” (23). Now my friends have dead babies. “No blueprint. A dead architect. Only blush, no bride” (23). In Milk Fever I was forced to remember how on Sundays our mothers knelt and not only prayed but you should have seen the potpourri that poured from their fingertips and how we smelt, not death, but dreams of our own houses and sulking children. Now we are far flung vicars of Venus, dead Gods. A wrench whispers in this elixir nest.

Even though Milk Fever does not offer a definite ingredients list as to the sorcery or mixture from the blood to the bone that assembles and endures the body’s heat, converges, convenes, intersects, connects, touches, liquidates, bears, suffers, undergoes, endures, the heat, the heat, one is constantly forced to ask of this sorcery or mixture from the blood to the bone that makes milk. “Milk blackens on burning chests” (24) and “I can’t reach my mouth to touch its tongue” (25). I am no chef; all I know are dead cows, dying women, and snippets from the Bible.

So there I am, looking at Rosa, thinking: Rosa, we share so much, you and I. Rosa, don’t be surprised when your tits start fleshing out and a multitude of hands rummage and intrude for your milk. Rosa, be careful. Rosa, you also look so tired, as if this is the last and final rest before departure, where are you going?

Of course the enigma of Rosa’s life haunts me all the time. Where is she? Is she safe? In the abattoir? A milk farm?

Rosa, are you okay? Rosa, don’t forget:

“[o]ur forebears keyed cars and siphoned colour. Sugared engines. Smashed windscreens. Practised black magic in orphanages and inked saints into tanned arms. Fed homes eucalyptus and beer. Built cities from copper buckets. Warmed milk on angry stoves. Measured time. Plotted stars” (23).

When I look at Rosa in what I assume to be the only surviving picture of her, I cannot help but despise the unnerving green fly that rests on the spine of her face; which brings me to my next epiphany: another thing that women share with cows is the nauseating presence of flies, and in the context of my daily life these flies come in the form of both living and dead men.

Sometime during this month I was terrified at having to write my first book review. I was in a bar with friends and it was nice, but the review sat on my neck like cargo. I was also expecting someone—a boy. Someone came, someone left with the intention of coming back, and someone never came back. I first realised I had been stood off when the purple of my faux fur coat started wearing off and my ponytail was keen on leaning over to the left side refusing to centre, my lipstick had changed shade. The motherfucker. It changed everything, not with him, I had always known where I stood with him, what I wanted. I was no victim. I was only the sorry ass that believed the best piece of shit (and shade) ever thrown to womankind: I will be back in no time. Nigga!

The next day when I looked at Rosa’s picture, trying to finish the review, Rosa changed. She was no longer the sexy holy cow with curling toenails and a pout. She was waiting. Rosa was waiting, like how Sethe waited for Halle. Sethe waited for Halle till she gave birth in a river with a white girl who only wished for velvet nursing her. See how water, blood, bone, and fire make milk? My initial reaction at being stood off was not rage, that came after, but more of an aha moment. Men are flies and women are cows. I was waiting, like Rosa, like Sethe, like Megan. I was the lady in purple. I was Andre 3000’s Caroline; sweet Caroline whose vagina did not smell like roses and she had to know that.

Remember when they took Sethe’s milk, like she was a cow? Sethe is not a cow, Sethe is not a cow.

Rosa, what makes milk?

Mother makes milk.

Oh Rosa, silly hunchback, sad lover.

I am always thinking of dead women. I am always thinking of my dead mother. My mother was a Stuyvesant Smoking God. Her tongue could scorch the devil out of you, especially on Sundays when, if any of, my brothers’ footsteps messed up the house. She was dangerous, and a lover too. I stopped sucking her titties when I was four; all her blood and bone, mashed up to milk, in me. She named me after her mother, and always I would ask if she loved her own mother, since I never knew her. It is true that some poems are not written by us, but for us:

in this shop of horrors: where daughters know

their mother’s mother only in photos

only in second-hand memories knowing she would have

loved you only by the

echoes in your mother

how lonely

is this:

calling someone a name when she is a stranger

when she does not know mine

when her daughter clasps her compact longing to touch

the face locked inside glass,

her scent less potent

each time it opens.

—“Origin Myths,” Ross.

We are no longer false prophets, dead cows, or even the sorry asses of history, but seers and givers and something else more scary—writers. Milk Fever is successful in the way it stages the myth of origin as well as a myth of return. Ross takes us through a journey in and out of the ocean’s surface—also read Female Body—without destabilising the desire for home or even an authoritative voice, because as Yvette Christianse writes in Imprendehora: “all the vanities will be laid low, even to the oceans floor” (44).

Ross settles into multiple points that articulate origin and the result is the fever that affects some cows and women after birth—the result is also haemorrhage, it is the sea eating up all the land, blood that swims, “and shores heeding the flood and yet [the] water won’t wash away the fault lines of a body history interrupts” (81). Reading Milk Fever alongside Christianse’s Imprendehora, it is evident that the human and the non-human are interconnected in a way that is essential, yet absent, in current feminist discourse and writing. The collections sift through traces and fragments in search of a freshly hewn language through which new worlds and subjects might emerge on the other side of rapture, a language that defines self-making in conditions of displacement. Milk Fever is concerned with notions of genealogy, the entanglements of departure, the possibilities, as well as the foreclosures, of freedom. Water breaks silence, and as Gabeba Baderoon stipulates in her 2009 essay “The African Oceans—Tracing the Sea as Memory of Slavery in South African Literature and Culture”: “Silence has a complex history.” Milk Fever is an explosion and a testament to how “the sun turns heavy into the sea” (30); and after reading it I too want to “open my notebook; savour the slow-ripening quiet, of a morning that is mine, a small freedom found” (68).

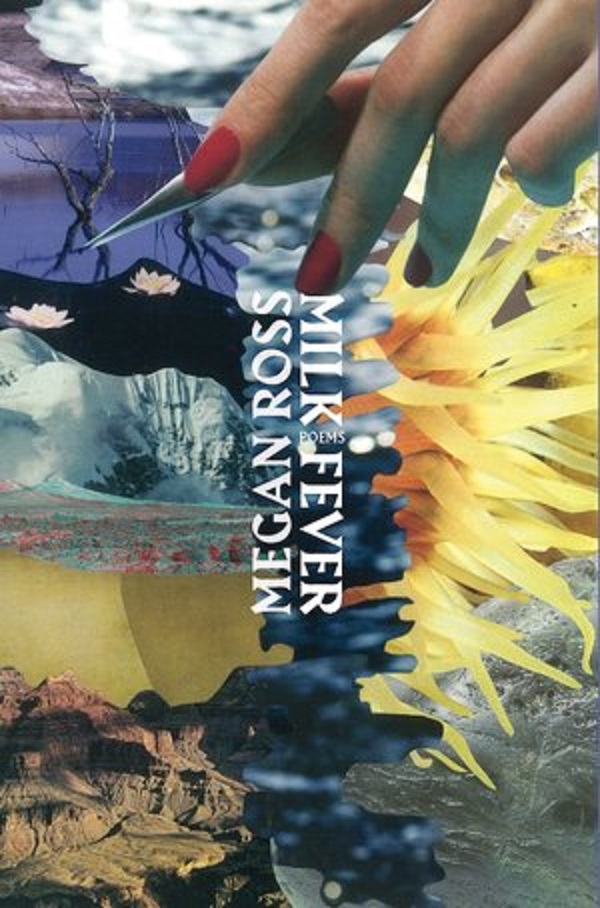

Megan Ross’s Milk Fever is published by uHlanga Press. Get it HERE.

ABOUT THE WRITER:

MAPULE MOHULATSI is a reader and writer. Her work has been published in Enkare Review, Itch Magazine, and This Is Africa, amongst others.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions