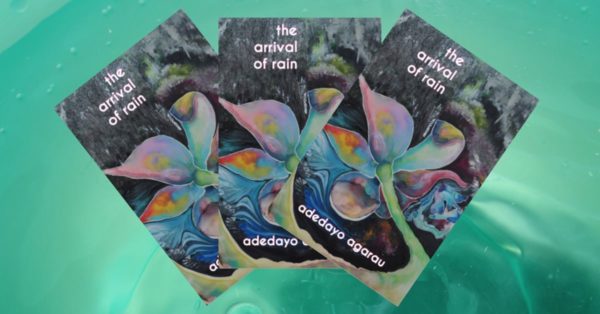

The opening lines of Adedayo Agarau’s poetry chapbook The Arrival of Rain (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2020) goes: “broken every time the door opens/or is banged against your face/you can count your losses/but do you remember my name?” The poem is titled “look how far i’ve come,” and the reader will most likely pause after reading it. What follows is lamentation and heartbreak: “i am with you inside the room/the ground is littered with pictures/of girls who do not love you back.” In this manner, the first series of poems explore brokenness, emptiness, and sadness.

There is spirituality in some of the poems. “Baptism” reads like a prelude to an exorcism:

12 candlesticks bounded by the grip of your hands / your knees narrowed into the marrow of silt

fire x7 / Jesus x7 / your white sultana carrying the embodiment of the sea’s grief the demons

The voice, haunted by loneliness and quaking to untenable emotions, assembles himself to curb the demons he has identified. He shows an attempt to understand himself in “the first portrait of me as adedayo”:

let’s assume the body is an estrangement/a beach house washed up in a sea/ the tender waves calling calling calling/ let’s assume the body is a little flower/ praying for the sun pleading to be left alone in the wind/ alone with the stars in a night sky /alone with the grief trapped in the ship of its own sea /let’s assume the body is a departure.

It is in this same fashion that he writes the poems as portraits, as a medium of self-seeking, a poet trying to unravel what bothers and torments him. The poem “untitled” is remarkable in its performance of paradoxes and its tendency to elude deeper meanings beyond the line. I was struck by these lines:

my mother’s face is a sea of drowned ancestors / i can tell that her unhappinesses are helium balloons in the sky / a god crucified by a kiss hangs around her head / grief is what we have in common / but i am never home to name my losses.

The paradoxes of “unhappinesses” and “helium balloons” and of sharing grief with the home keeper and yet never being at home to losses—they are laid out well. The most striking, perhaps, is of the mother being covered by a god betrayed by a sign of love; it brings to mind something about love: its power to redeem and disarm. It is even more haunting that the poem projects grief when it is really just love. In many ways, this could be said of the collection. Most of what it explores—self-seeking, empathy, heartbreak, spirituality—centre on deep intimacy, love.

In “what it means to be freed by your country,” Agarau returns to the social consciousness explored in his earlier chapbook, For Boys Who Went, which is dedicated to Daniel Usman, one of the victims of electoral violence in the 2015 general elections. Agarau’s social consciousness is important in light of his belonging to a generation of writers with dwindling social consciousness. As these writers gained prominence over the years, they changed the landscape of African poetry. Otosirieze Obi-Young has referred to them as “the confessional generation.” The poets especially fit into this category because of their knack for self-expression. One achievement of confessional poetry, like Agarau’s in this chapbook, is a personal engagement with the reader, and a subtle poking of the subject of heartbreak.

The Arrival of Rain explores self-discovery over an expanse of torment, heartbreak, empathy, loneliness, and grief—all with a tinge of spirituality, under the shelter of love that keeps trying despite being knocked out. It is a testament to a poet trying to find his way back to himself. It is commendable but not perfect. Some of the lines could have been better pruned, and some of the poems would have been just as efficient if they were shorter. The structuring is interesting, but a few poems seem over-dependent on it. However, considering the evolution of African poetry, the last concern could be a plus in the eyes of another reader. This is a welcome book from one of the most consistent young poets in the continent.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Michael Chiedoziem Chukwudera is a journalist working for Voice of the East Media. His writing has appeared on African Writer, Brittle Paper, Kalahari Review, Praxis, and elsewhere. He enjoys reading and traveling. He is interested in the often avoided topics by the Nigerian and African intelligentsia and hopes to spark some discussions on them. Follow him on Twitter and medium: @ChukwuderaEdozi.

https://sketchfab.com/tapdoanmasan October 26, 2020 07:12

I wanted to thank you again for that amazing blog you have created here. It truly is full of useful tips for those who are definitely interested in this specific subject, in particular this very post. Your all actually sweet along with thoughtful of others as well as reading your website posts is a superb delight to me. And such a generous treat! Jeff and I usually have enjoyment making use of your points in what we must do in the near future. Our list is a distance long and simply put tips are going to be put to fine use.