Dreams are truer than reality.

You know full well that only dreams come true.

***

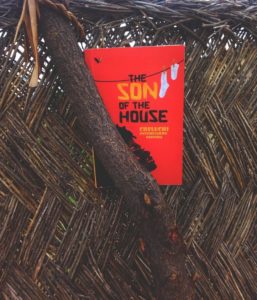

The novel starts out late at night with a dream and thundering rainfall, followed by a pregnant woman dying in a pool of blood, and her baby being essentially stolen by Babakar Troare Jr, the village doctor. Who wouldn’t want to read on! When I think of Maryse Conde, I think of stories with a ton of magical flair. Waiting for the Water to Rise, the English translation of an older work, was published last month. It is a moving read for the way the language gently draws you in. Conde’s language is dreamlike, suffused with poetry. The novel is enough of a page-turner, but what really keeps you transfixed to the page is the writing.

The magic of this book begins with the opening scenes. It is night time, and Babakar hears the ring of the doorbell through the deafening sound of the rain. The stranger at the door tells Babakar there is an emergency and leads him to a shack stationed by a Mahogany tree. By all accounts, “it was one of those nights ripe for the unknown or the unusual,” and Babakar’s life was indeed about to change forever because in that shack lay a woman in labor. The woman is Reinette, an illegal farm worker from Haiti. Babakar, the village doctor, has arrived too late, so she dies in a pool of blood but leaves behind a girl. Seeing her “chubby cheeks” and “head of thick black downy hair,” Babakar gets the idea that the baby is a sign from his own mother. So, he takes her and names her Anaïs. She becomes the center of his world, making his life a little less lonely and numbing the traumas of his past.

If the story had ended here, Waiting for the Water to Rise would be a family romance about how a disturbed and lonely man turns into a loving father. But Condé has other plans for her characters. Their bond tells a larger story of Black people losing homelands, surviving trauma, but finding ways to rebuild. Babakar is a Malian doctor living in Guadeloupe. A handsome recluse, he is tall, dark, and mysterious. But what is a middle-aged doctor from Mali doing in Guadeloupe, living alone in a community where he is despised? What are the chances that two strangers, a man and a woman, from two different Black worlds, Mali and Haiti, would meet at the crossroads of a child’s birth?

Unraveling the strands of Babakar’s life takes the novel 40 years earlier, on the banks of the River Niger in a Malian village. The story involves Thecla Minerve, a dark-skinned Guadeloupean woman with blue eyes and her romance with a descendant of the Bambara empire of Segu. It also involves the breakdown of Mali’s post-independent government. Part political drama, part crime story, that part of the story is gripping. It explains why Babakar has to leave Mali behind in search for a new life but also why his attempt to build that life in his mother’s homeland fails. Until Anaïs comes into his life, Babakar feels rootless and lost. Years later, when he learns that Reinette’s dying wish was for her daughter to return to Haiti, he embarks on yet another journey.

Through Babakar’s journey from Mali to Guadeloupe to Haiti, Conde links Black lives and worlds in a common experience of displacement. When Babakar arrives in Haiti, two other people join the story. Estrella is Reinette’s sister and Foud is a Palestinian hotelier. Just like Babakar, they are both given the space to tell their back stories. And like Babakar, their stories are about dispossession and displacement. Babakar’s mother is descended from enslaved people. He is born in Mali, which he flees and ends up in Guadeloupe, which he also flees, ending up in Haiti.

Through Babakar’s eye we witness a certain kind of movement of global Blackness that takes the form of fugitivity—always on the run, always in search of freedom and new kinds of community. As painful as the history might be, it claims a global connection for Black people. The redemptive message in the novel is that this connection could be the basis of rethinking and re-making community. There are glimpses of some other kind of basis for the Black experience because what brings all these people together is Anaïs. Her life evokes the possibility for something new. In a story that has traced a complex history of exploitation—from slavery to colonialism to the brutal violence of failed states—the tenderness that is centered on Anaïs’ life is preserved.

The novel is ultimately about interrogating what brings us together. In the face of displacement, dispossession, and grief, we have to find other ways of anchoring the connection we share with others. Blood cannot be the only legitimate basis for making a family. Chance encounters, the demands of an ancestor, shared experience of personal traumas, and a fervent hope for something better can all serve as a basis for bringing people from different parts of the world with different experiences together to share something close to a family bond.

************

BUY Waiting For The Water to Rise: Amazon | Bookshop

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions