The first time I had a copy of Hegel’s writing on Africa in my hands and read it, I was struck by how short it was. A few pages only. Clearly, Hegel did not want to think of Africa for much longer than he needed to. One can’t really fault him. He had his eyes on a much grander project. And there was Africa blocking his vision. He saw Africa as an impediment that had to be cleared away to make space for an idea he helped invent: the idea of world history. Hegel wanted to erect a magnificent world-historical edifice that would run from ancient Asian civilizations all the way up to Europe.

Clearly, Hegel did not want to think of Africa for much longer than he needed to. One can’t really fault him. He had his eyes on a much grander project. And there was Africa blocking his vision. He saw Africa as an impediment that had to be cleared away to make space for an idea he helped invent: the idea of world history. Hegel wanted to erect a magnificent world-historical edifice that would run from ancient Asian civilizations all the way up to Europe.

But if this edifice is so big, why did Hegel not just find a way to fit everyone in? Why did he have to place someone outside and why did that someone have to Africa? The first question is easiest. Hegel had no choice but to leave someone out. It is a rule of thought that Hegel did not make himself but inherited from an old philosophical tradition. Take for instance the simple idea of a house. A house is a house to the extent that it can keep somethings and some people inside while keeping other things and other people outside. A house is defined by exclusivity or by its ability to exclude whatever it believes to be the outside. If we think of Hegel’s world history as a kind of edifice, we can kind of see why for him to preserve the integrity of the whole set up, he just could not include everything and everyone. Someone just had to get bounced. Photographs behave in a similar way. As we all know from having been photographed, cameras always have a frame. Frames are great because they put things in focus, but they can do that only because they leave stuff out. Africa, in a sense, is the stuff Hegel’s world historical camera refuses to enframe so that it can frame a world history. But the good thing is that, as I hope to show in a series of posts, this process of exclusion is not the only way to do history.

Why Africa? As a Nigerian might say, this question is the koko. It is the heart of the matter. For this reason, my response would be drawn out over several blog posts and would take different forms. I want to draw a picture of Hegel’s Africa framing History as the picture of the world. I want also to think of those who over time have tried to think with and against Hegel. Hegel and his Africa are certainly ghostly in the sense that they have simply refused to die a complete death despite the passing of time. They haunt writings from diverse fields of African thought. Strange bed fellows like Conrad and Achebe and the Negritude Philosophers and Soyinka’s Ogun were all trying in their own unique way to converse with Hegel, whose claims about Africa they found both astonishing and displeasing.

The puzzle continues….

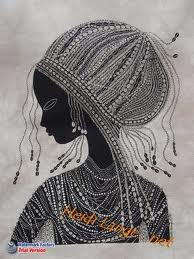

Photo: indusladies.com

Fabbeyond January 03, 2019 09:04

Actually Hegel is speaking about southern Saharan Africa aka black Africans (negroid morphological southern Saharan Africans )