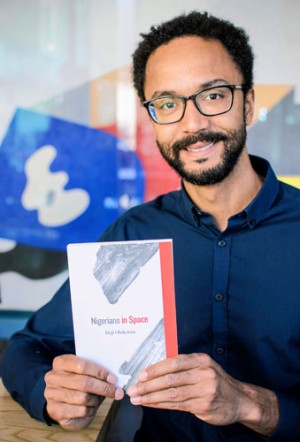

Deji Olukotun’s novel, Nigerians in Space, is one of the most entertaining novel about Africa to come out this year. It’s a quirky, multi-city, fast-paced noir fiction piece about a Nigerian lunar geologist who dreams of leading a Nigerian space mission. But as with all things Nigerian, things get a little more complicated than he imagined.

After I read the novel, I knew I was going to review it {HERE}, but I also wanted to chat with Deji, get inside his head, try to understand how he created this richly textured and fascinating fictional world of space-traveling Nigerians.

Enjoy!

Why did you seek out writing as a vocation?

Why did you seek out writing as a vocation?

I’ve written stories for as long as I can remember. When I was very young, I used to write my own fables in imitation of Aesop. Each one had a moral at the end—that was my favorite part. I continued to write through high school and college, but I was often frustrated that I could not express what I wanted on the page. Once I enrolled at the University of Cape Town in the MA program in creative writing, my teachers gave me the tools to write what I wanted and I haven’t stopped since. It’s a wonderful feeling.

What was the inspiration for Nigerians in Space—the “a-ha!” moment?

Well, there are two main plotlines in the story. The inspiration for the character Thursday Malaysius, who is involved in the illicit abalone trade, emerged from my human rights research. I came across a paper at the International Security Studies office and I thought it would be fascinating to explore this trade in which poachers from small fishing villages are able to make a living in a business that stretches all the way to East Asia. So I traveled to one of those towns and spoke to factory workers and prosecutors. The idea of a Nigerian lunar geologist came out of a question—what would the world be like at night if all our streetlamps produced moonlight? I worked backwards from there.

You said in an interview that while you like reading “purely literary” fiction, you prefer to write plot-driven narratives. And Nigerians in Space is very much in the noir category. The plot is schizophrenic—and delightfully so. It jumps around a lot and for a while the reader is not sure how the characters and spaces all connect. But by the end, seemingly unconnected individuals, spaces, narrative threads, and even objects come together to form a rather captivating narrative collage. What inspired such a plot treatment?

I admire literary fiction—which is a broad category—because of its ability to experiment with form, time, and especially character. You can read about the life of a character in a day and, if done right, it can be compelling and daring in a way that genre fiction cannot. You’ll see that I reference Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse in the book. I actually had a few pages devoted to To the Lighthouse, but I had to cut it for editorial reasons. I read To the Lighthouse in high school and it blew my mind—here was a true master of language and craft telling a story in an original way.

I grew up in a family of storytellers, so I always loved hearing a good yarn. But more specifically, my professor at UCT was Mike Nicol, and he was in the midst of writing his dazzling Revenge Trilogy, a hard-boiled noir story set in and around Cape Town. His passion for the genre made me focus on plotting, and this made it possible for the different threads to come together. It was maddening at times to keep track of all the little details, but I’m glad you liked it!

Lauren Beukes is South African and writes a novel set in Chicago with American characters. Chris Abani is Nigerian and writes a novel  set in Las Vegas with a South African character. You’ve written this novel with characters from all over Africa and set in Houston, Cape Town, Basel, Paris, Abuja. Why do you think African writers are now so interested in stories that take place elsewhere?

set in Las Vegas with a South African character. You’ve written this novel with characters from all over Africa and set in Houston, Cape Town, Basel, Paris, Abuja. Why do you think African writers are now so interested in stories that take place elsewhere?

I think it’s great that African writers are writing about the world as they see it or as they imagine it to be. There are plenty of stories of people from other countries writing about Africa, often in an exploitative way, so it’s great that the publishing industry is willing to celebrate African voices writing about non-African cultures. For my part, I had been fortunate enough to have visited or lived in almost all the places I wrote about in the book. This made it easier for me to write about them.

Nigerians and 419 scam. Nigerians and corruption. Nigerians and Boko Haram. Nigerians and…well, you name it. But Nigerians and space? In other words, your novel is about two things—Nigerians and space travel—that not many people link together. Was it challenging getting someone to publish it?

It was important for me to find a literary agent who believed in me, Gary Heidt. From the very beginning he understood exactly what I was trying to do—tell a non-stereotypical story with African protagonists that was plot driven. We actually had almost 10 offers immediately after we sent the story around. It was fascinating: literally 10 times the associate editors brought it to the editorial room because they were excited about it. But their colleagues shot it down at that phase. I don’t know why that happened, only that it was heartbreaking to get that close so many times. In the end, I was fortunate to connect with Unnamed Press. Their team is top-notch, all former editors and publishers, and they have gotten completely behind the story.

In the character, Bello, you do something strange with the figure of the praise singer. I’d never have thought of the Yoruba figure of the praise singer as a kind of spellbinder, a dream weaver, a quasi-conman, someone who has the power to transform language into something bewitching.

His character was inspired in part by Wole Soyinka’s play Death and the King’s Horseman, which explores the notion of the praise singer in brilliant fashion. With Bello, I was seeing what would happen if you had someone who was completely versed in the language of the West—public relations, marketing, and advertising—and combined these skills with a traditional role. The praise singer is at once a musician and politician, a sort of bridge, if you will, linking together generations of royalty in Yoruba culture. More than that, Bello dares to dream, to imagine a better future for Nigerians than the politicians he must serve.

Melissa’s skin! To be honest, I was a bit bothered by how much I was both creeped out by and attracted to her body. What idea of feminine beauty is implicit in her strange body?

Melissa came out of a number of strange experiences. Cape Town is a major stop on the global fashion circuit, and a close friend of mine—who is also a writer—was a fashion model at the time. (There were very few fashion models of color in Cape Town, incidentally.) With Melissa, I wondered: if black is beautiful, what happens if you’re not black enough? And in Africa, the absence of color—or being albino—can lead to a death sentence in some cultures. At the same time, Melissa is the daughter of a freedom fighter who helps with the South African liberation movement, so she has a public role. I like the idea that your greatest weakness can become your strength and this is her trajectory. Nnedi Okorofor also wrote about albinism in her stories, but I didn’t know that until well after I’d finished my book.

What do you love about your novel, Nigerians in Space?

I’m really proud to have written a novel that features African protagonists, and that which also takes advantage of my American heritage. I worked extremely hard on the prose, on the pacing, and on making the story as authentic as possible. And I wanted to tackle African stereotypes, not just in Nigeria but also in South Africa. I grew up around scientists—my father is in the biotech industry, so we always had scientists dropping by the house—and I wanted to give the African characters both agency and intellect. I think they have them.

Above all, I’d love for readers to enjoy the ride. Go spear-fishing with Thursday as he hunts for abalone; walk the catwalk with Melissa; and follow Wale as he pieces together the crimes. This a story after all.

What is your day job?

I’m a lawyer by training and I’m privileged to be able to work with writers every day at PEN American Center. I founded our digital freedom program, which protects writers around the world who are persecuted for using digital technologies—going to jail for writing a poem on Facebook or Twitter, for example. And I work closely with PEN Centers in South Africa, Haiti, Myanmar, and, yes, Nigeria. It has been an amazing ride but believe it or not, not very good for my writing. I’m overwhelmed by books and I don’t have much time for my own work. Could be worse, though!

Links that Connect | Catherine Onyemelukwe August 09, 2014 22:10

[…] often find fascinating pieces on her blog, like the recent review of a new book by Deji Olukotun, Nigerians in Space. The reviewer makes the novel sound like a little bit of chaos and a lot of […]