There was an old woman with a ragged scar on her cheek who lived alone on the outskirts of Dahomey. The people all knew of her and would gawk and whisper when she passed them in the market square — the only time she entered the city — to buy fruits and vegetables.

At night, they said, as if following some hidden instruction, she would jump and kick. She would dive on the ground and crawl then stand at attention, looking at her surroundings with sharp eyes. The boys who sneak out to watch her laughed and jested. One day, she caught them, then the laughing stopped.

So did the spying.

When the sun was going down and evening approached, three children, two boys and a girl, none older than 9, would go to the woman’s lonely hut at the edge of all they knew, and they would sit on the ground in front of it and wait for the old woman to come. And she would tell them stories.

She told them stories of old kings, stories of Dahodonu, the founding father, stories that nobody in the village knew. She would tell them stories of Mawu-Lisa, the mother-father god from which all things sprang. She could make them laugh with the stories of people in the kingdom. She only came once a week, but she knew who was being unfaithful and with whom.

She could also make them scared.

So scared that they would walked back to their homes in the village, trembling and flinching at the sight of their own shadows. But they loved hearing the old woman’s stories, and she, in turn, loved telling them.

Today, they went together to the woman’s hut, which was covered in swirling marks and which none of them had ever seen. Wind blew an old charm at her hut opening this way and that. The air was filled with the sweet smell of the woman’s cooking at her large pot, on a small fire next to her hut.

There were bones of a guinea fowl nearby.

The three of them went slowly to the woman who had her back to them; they had heard about the incident with the boys and knew not to make any sudden moves around the woman. She was stronger and faster than she looked; one of the boys had been a soldier.

“Mama,” Oumaru, the eldest of the three, said quietly. “We have come for today’s story.”

The other two boys, Glele and Tegbesu nodded.

The woman did not turn her back. She continued stirring the stew. “Sit,” she said, her usual energetic voice was strained, “eat first. Story after.”

The children nodded and sat as she handed them clay bowls and spooned stew for each of them. They ate in silence. She handed them water. The food tasted as nice as it smelt.

After collecting their plates, she sat in front of three of them. The sun was tumbling through the sky now, and the light cast her in an occult glow.

She coughed. “Children,” she said, “I have spoken to you of a lot of things. I have told you the stories that have been passed down from age to age. Today, if you will listen, I will tell you the story of the witch, the one they say used to live here,” she gestured to the hut, “in this very place.”

“So,” Glele said, he was the youngest and the quietest, “the stories are true? There really was a witch?”

The woman smiled at the boy. “All stories ever told are true,” she said, and looked at the sky that had exploded in a cascade of orange light and dark blue darkness. Then, quietly, “Stories are where memories go when we forget them.” She continued looking at the sky, and the children looked nervously at each other. She did that sometimes, stared into emptiness. It was like her body was there, but her mind had travelled to a different place, and time.

There was hesitation and then, “Mama,” Oumaru prodded.

“The story,” the old woman jerked back, “is from long ago… a time before now. Tell me, my children, I forget, who is the king now?”

“King Kpengla,” Tegbesu answered. He was the roughest of all the children. Many a cane had been broken on his back.

The old woman nodded and smiled. “Kpengla,” she said, “he was still a little child by then. No bigger than any of you.” The children giggled at that; it was funny to imagine their regal bone faced king a child like them. The woman continued, “His father before him was King Tegbesu, after whom you are named, little one. Names are important. They are omens that can foreshadow one’s future.”

Tegbesu beamed and stood up with both arms on his waist. “Did you both just hear that?” he said. “Mama said that I will be king!”

“Don’t be silly, Tegbe,” Oumaru chided. “Only someone of the king’s royal line can be king.”

Tegbesu looked to the old woman for support, but she just shrugged and said, “Sorry.”

Glele said nothing.

“In those days,” the woman continued her story as the fire crackled and the sky darkened, “the role of Kpojito had just been established and Hwanjile had become the very first Kpojito — Queen Mother.

“But, in the twentieth year of his rule, her son, King Tegbesu, son of Agaja, fell dangerously ill and entered a dreamless sleep. Herbalist after herbalist came and went with no success. All the Vodun practitioners in the land were called, and they came, but they too failed to bring the King to health. An alliance was made with the Oyo empire,” The woman scowled to the east as she said this, “and they made no progress as well. Weeks passed, and then months, and then a year with the King asleep, and still, no cure was found.”

“A…year with no king,” Glele breathed, his eyes to the ground. “It must have been bad.”

“It was,” the old woman nodded, “There was chaos in the land, and the white devils who invaded our land were making deals with generals who were branding and selling our own people in exchange for guns and iron. And so, a council was called, consisting of the Queen-Mother, Hwanjile, and the four elders, with the migan — consul, who made up the King’s court. They had been running the Kingdom in his unfortunate absence. Hwanjile sat on her throne and looked steely at them as the elders nervously shuffled in their seats.

“‘Our queen,’ one of them said, ‘we have tried everything. But nobody, even the Yorubas, has managed to bring our king out of his slumber.’

“‘We have not tried everything,” said the migan, a towering man called Akaba. ‘They say there is a witch,’ he said, ‘that lives on the outskirts of the kingdom.’

“The queen gave him an icy stare. ‘Then why,” she said, ‘are you just bringing this to attention now, Akaba?’

“‘It was to be a last resort,’ he responded, meeting her gaze. The queen stared at him for a moment longer and turned to the elders, ‘Send ten of the fiercest warriors and let them bring this witch to me. Today.’”

“I want to be a Dahomey warrior,” Oumaru said, clapping her hands.

“Me too,” Tegbesu said.

Oumaru scowled at him. “Only women can be Dahomey Warriors.”

“I can be the first,” Tegbesu replied, folding his arms.

“That is not how it works,” Oumaru said with her fists balled.

“Why can I — ”

“Did they find the witch?” Glele said, raising his head to see the old woman.

“Yes,” she said, “just like the Consul had said, the witch was in the hut. The soldiers sent were among the fiercest in the land, and they had brought a new recruit along with them, to show the young girl how it was done being in the force.

“They marched to the hut with gusto and vigour: they were part of the greatest force in Africa and had never found an enemy they couldn’t conquer. They busted into her hut, armed with the sharpest swords and the strongest shields, expecting a fight they would tell for years to come.

“They were expecting to be hit by the spells of a strong witch, but all that hit them was the smell of stale beer.

“They did not find what they thought was a witch but instead they found a woman lying face down on the ground, empty calabashes that were once filled with drink scattered across the room. The woman looked to be young, not even 30, but her hair was wild and her clothes faded and old. A black cat with curious eyes was licking itself clean in the corner. Cobwebs had made a home in the hut, and the woman was there, lying in the middle of the mess.

“The warriors were puzzled, could this really be the witch? Regardless, they picked her up with scrunched noses as they discovered the source of the smell, and they marched her to the kingdom.

“Passers-by who are still alive from that day would tell you that though she looked and smelt like a mad woman, the eyes she used to inspect the people and the kingdom were not addled by alcohol or muddled by time or madness: they were sharp eyes, as sharp as a hawk. They brought her to the court and threw her on the ground to kneel in front of the queen mother.

“‘Speak your name,” Hwanjile said, sitting on the throne of her slumbering son. The woman did not even stand as she mumbled something.

“‘What?’ the queen asked, leaning forward.

“The witch raised her head, and one could almost see beauty underneath the earth and grime that looked to be a part of her face. Smiled a sharp smile and said, ‘I threw it away.’

“The consul, who was also seated, almost smiled. ‘You threw away…your name?’ he asked.

“The woman shrugged. ‘I did not need it anymore,’ she said, ‘so I threw it away.’

“The queen’s fist balled, and her voice became an octave higher. ‘Then what,’ Hwanjile said, ‘do we call you?’

‘Whatever you want,’ the woman replied, smiling her sharp smile again.

“‘Witch, we have called on you because we have a problem,’ the Consul began, ‘our King is — ’

“‘Dying,’ the woman said.

“‘What?’ the Consul replied.

“‘Your king is dying,’ The witch replied. ‘In a day’s time, his body will give up in his endless sleep, and then, he will die.’

“‘How do you know this?’ The Queen Mother asked with narrow eyes.

“The witch looked at her for a moment and then another, then said, ‘I know things.’

“‘Can you heal him?’ the consul asked, practically pleading.

She thought about the question for a moment and then said, ‘Yes. I can.’

“Hwanjile was outraged. ‘How can we trust this dejected woman who drinks like ten men? What if she was the one that did this in the first place?’

“‘If I wanted to kill your king,’ the witch said, loud and clear enough for everyone in the room to hear, ‘he would be dead by now, a hundred times over.’

“There was silence in the room. They could feel the truth in her words.

“And then, ‘What will you demand as a fee?’ the consul asked.

“‘You are in possession of a very old necklace. It’s in your King’s private chambers. It has three dark jewels on them in the shape of a diamond. I want it,’ She said.

“The queen looked like she was going to say something, but the consul interrupted. ‘It is yours,’ he said, ‘whatever you need to help you, we will give.’

“‘A bath,’ the witch answered, scratching her armpits, smelling them and wincing, ‘and an assistant to help me search for ingredients for the cure,’ she looked around the room and saw the youngest warrior still standing there looking out of place. ‘You,’ she said, pointing to her, ‘what is your name?’

“‘Beolice,’ the young girl answered with her chin up, just like she had been taught.

“‘Beolice,’ the witch echoed as if tasting the name. ‘You will be my assistant and before day break tomorrow, we will find the cure to the king’s ailment. Now, man,” she said, looking at the consul, ‘my bath and my necklace.’

“‘Your payment will be given after the king has risen,’ the Queen Mother said, ‘not before.’

“The witch did not say anything for the longest while as she stared at Hwanjile, then she said, ‘So be it.’

“The witch’s bath was arranged, and new clothes given to her as servants flocked around her and braided her hair, all the while Beolice stood by, watching, her hand on her spear.”

Glele yawned, and the old woman smiled as she stoked the fire, sending sparks to heaven.

“When all was done,” the old woman continued, “the witch took Beolice through the Sacred Forest where they would find the ingredients she would use to cure the king. The witch walked into the forest dauntless, but Beolice was visibly scared, as she clung to her spear. They reached a point where the witch, as if sensing something in the air, stopped. A cat that looked suspiciously, like the one they had found in her hut, appeared from the foliage and purred against her leg. The witch smiled and stroked its back.

“‘Why do we stop, witch?’ Beolice demanded. The witch only turned her head and smiled a wicked smile.

“‘Take my hand,’ she said.

“Beolice regarded the hand with apprehension. ‘No,’ she said.

“‘I do not know how long we have left,’ the witch said. ‘She has most likely sent someone after us. Time is not on our side. So, Beolice, take my hand.’

“‘Who will send someone after us?’ Beolice asked, almost laughing. ‘I am a Dahomey warrior. I checked our track as we walked. We were not followed.’

“The witch said nothing. She just kept her hand outstretched, which Beolice grudgingly took and found to be cold, far too cold for anyone living. Still, she held on. And the witch held on to her.

“There are things that can be communicated, children, things that can be said with words, this is how we pass things on from person to person.

“It is the way of us human beings.

“But the witch, she was not completely a human being anymore.

“Beolice gasped as knowledge flowed through her from the witch in blue electric sparks as the witch closed her eyes and concentrated. In a moment that lasted as long as it began, it was over, and Beolice flinched away from the woman, readying her spear.

“‘What was that?’ Beolice demanded. ‘Tell me, witch.’ Beolice levelled her spear at the witch’s heart.

“It was a sharp spear, made with hard iron and cooled with the blood of the enemies from Oyo. It had been used to cut through a man like he was cloth. But the witch, she only smiled. ‘You saw it,’ she said. ‘Did you not?’

“’You showed me lies,’ Beolice replied. Her teeth bared.

“‘I have no reason to,’ the witch said. ‘I am only here for my necklace.’

“‘That necklace has been in the palace guard for over a hundred years,’ Beolice said, ‘how can it be yours?’

“The witch put her face in her palms. ‘I was very reckless during those times,’ She said. ‘I was going through something.’

“The cat purred to get its owner’s attention, and the witch’s eyes widened.

“‘Behind you,’ she spat.

“Beolice did not hesitate as she spun and impaled her spear into the enemy that had managed to sneak up on them. But the intruder was fast and slashed at Beolice’s face, but she held her spear tightly as she looked into the enemy’s eyes, the dying eyes, of her general.

“‘Hazmat,’ she breathed. ‘No.’

“But there was no response. The General simply choked in her own blood. Beolice jerked her spear out and stared at the body. The witch was not standing beside her.

“‘You…’ Beolice managed to say, wiping blood off the cut on her cheek. It would leave a scar, she knew. ‘You told the truth. But why would she do this?’

‘” Nobody knows what evil lurks in the heart of men,’ the witch said, and then, ‘or women.’

“The witch observed the scar on Beolice’s cheek. ‘I can heal it,’ she said, ‘if you would like me to.’

“‘No,’ Beolice said. ‘I will keep this scar.’

“The witch sized up the young girl. ‘As a reminder?’

“‘When we train to become warriors, we are trained in hard blood and cold iron. We are taught not to rely too heavily on our swords, on our spears, or our shields. We are taught to become the weapon. And we do not leave, we do not stop, until the fight is won. When first blood is drawn, it is till the end. I do not keep the wound to remind me, I keep it as a promise.

“’I will end this.’

“The witch did not speak for a while but only nodded and began walking. Beolice did not ask questions, she knew where they were going and followed. She did not wipe her spear, there was no need: one more person would die by its blade.

“They got to the palace late in the night,” the old woman said staring back at the six eager eyes that stared back at her, “the witch worked quickly. With a touch, she disabled the palace guard with blue flames from her hands. They separated. The witch went to the king’s sick bed. Beolice went to his chambers where his mother slept.

“In a few moments, Beolice met the witch at the agreed point, a necklace with black diamonds in one hand, a bloody spear in another. Before Beolice gave the witch the necklace, she hesitated and asked, ‘But if you could heal the king,’ she said, ‘why did you take us all the way to the Sacred Forest?’

“The witch smiled. But it was a sad smile. ‘I wanted to see something,’ she said. ‘I wanted to see how far she would go.’

“Beolice nodded and handed the necklace to the witch whose stare lingered on it for a moment. Then she put it on and blue sparks flew around her body.

“‘We have Vodun in our place,’ Beolice breathed, ‘but it is not like this, not so…angry.’

“The witch smiled. This time, there was a bit of honesty in it. ‘I have had a lot of years to practice,’ she said and clicked her fingers. The cat walking from nowhere came to meet at her feet and regarded Beolice strangely.

“‘Goodbye, Beolice,’ the witch said as she turned and began to walk.

“‘Goodbye,’ Beolice said as she watched the witch, the saviour of their land, leave. The next morning, the people of Dahomey would wake up to a healthy king, two less Dahomey Warriors, a stolen necklace, and a dead queen-mother.”

The old woman stoked the fire, staring at the flames as they lapped the wood.

“Is Beolice still alive?” Glele asked, his finger in his mouth.

The woman smiled at that and touched the scar on her cheek. “Sometimes,” she said, smiling at the flames.

“Sometimes,” she echoed. “Now, little ones, it is time for you to go home. Come, I will walk you to the gate.”

*******

[Learn more about The Witches of Auchi Series here. Catch up on Episode One and Two here and here. Episode Four drops on Monday, Oct. 21.]

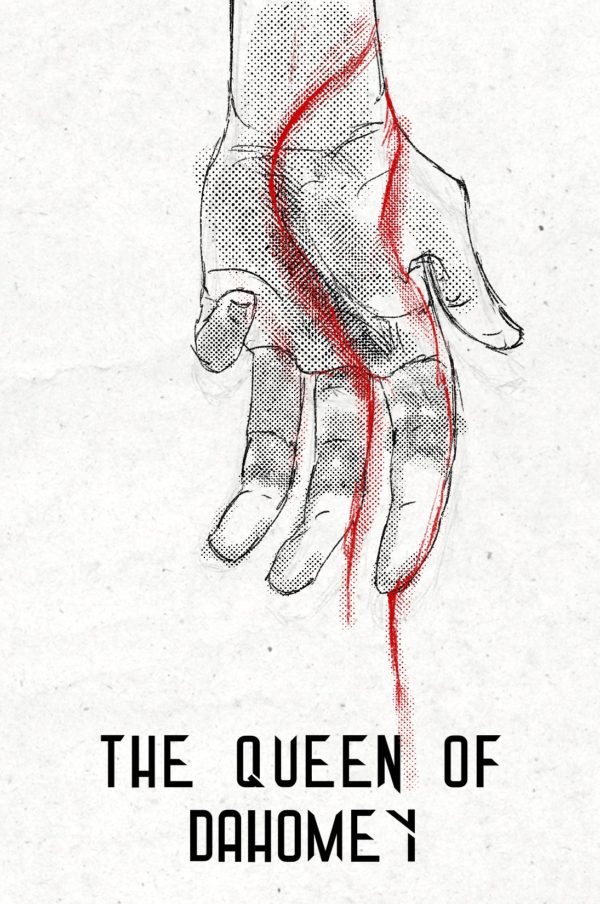

All art by Anthony Azekwoh

DarkQuinn August 26, 2022 11:58

A true masterpiece!! Movie-worthy❤️