This reflection, in a slightly different version, was first published on Bernardine Evaristo’s website: bevaristo.com. All images are credited to Evaristo. Visit the site to see more accompanying photographs.

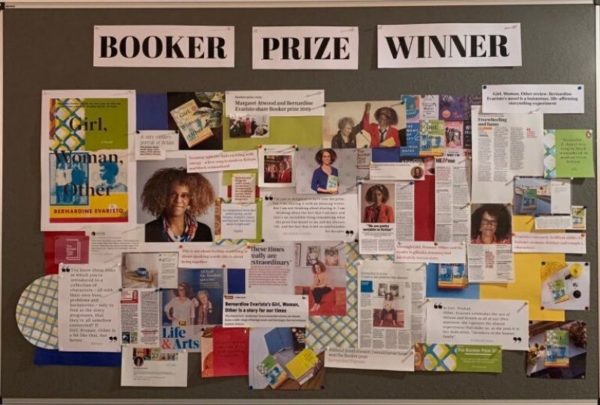

As a new year begins, I reflect on my amazing good fortune since winning the Booker Prize on October 14. Every day, I marvel at the power of this prize to revolutionise my career in every way imaginable, just as it did for many of my predecessors.

After Winning the Booker Prize

In interviews, I am always asked how I feel about sharing the prize and my reply is genuine and heartfelt. I am happy to share it, especially with Margaret Atwood, who is such an inspiring feminist, environmentalist, legendary writer, and generous person. I certainly don’t feel that I’ve won half a prize. My name alone appears on the Booker plaque sent to me, just as hers appears on her plaque.

I am the first black woman and first black British person to win it in its 51-year history. It is a bittersweet honour, because it’s not that other writers have been undeserving in the past, and yet only four other black women have ever been shortlisted. I do hope that another black woman will claim it soon.

The response to my win has been incredible. I have been bowled over by the celebration, warmth, and appreciation coming my way. I know a lot of people in the arts and literature, and I am deeply connected to my communities. I think my win signals hope for all those artists who dream of a bigger audience and all those people who want us to succeed at every level in this country and who feel that my win is also theirs—as I’ve been told many times. I’ve been in the arts for nearly 40 years, and for this to happen at the age of 60 has been a staggering experience, especially with a radical, experimental novel positioning black British womanhood at its centre, a third of whom are on the queer spectrum.

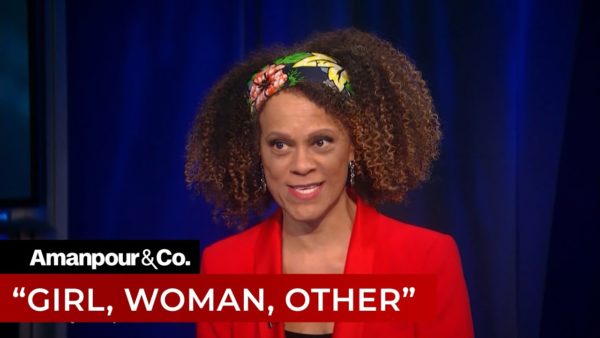

Since winning the prize, I’ve given more interviews in two months than in my entire career—most of them for major outlets: print, podcasts, and broadcast media, including my first invites to be interviewed on TV, including by CNN with Christiane Amanpour. I’ve actually lost count of the number of interviews I’ve given. To put this into context, I didn’t secure a single major interview in print media for the novel when it was published in May. Indeed, as far as I can recall, my only previous interview of any substance was in 2001, for The Emperor’s Babe in the (London) Times. I tend to be invited to be interviewed on radio. I guess the point I’m making is that while I’ve had a rich creative life and published eight novels, I was never cherry-picked for success, although I have long been well-reviewed in print media. However, while good reviews might enhance careers, they don’t, it seems to me, necessarily bring writers to wider attention. I’m not complaining, but I think people need to know that the road to this point in my career was not one of easy advantage.

A month or so after winning the Booker, I’d signed off on 28 translation deals, whereas previously I’d had only five translation deals covering my seven books—the first one published in 1994. Girl, Woman, Other has made the Sunday Times bestseller list for hardback fiction several times, and is currently selling more in a week than practically the entire lifetime of any one of my previous titles. As I’ve said many times, the book hasn’t changed, but the context of the book has changed. I wrote it to address the invisibility of black British women in fiction, and in so doing gained increased visibility as a writer myself. The novel is now floating off into the world to be read by people who would never normally encounter it, and in languages that range from Arabic and Georgian to Sinhalese and Taiwanese. My words, my twelve British womxn, now have a global reach, and for that I am deeply grateful.

The Making of Girl, Woman, Other

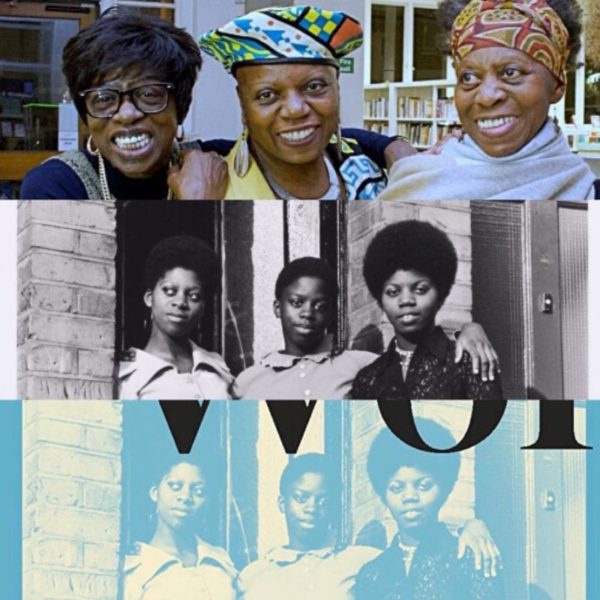

The Bailey Sisters in Clapham, a 1970 photo by Neil Kenlock, appears on the cover of the novel. It was found in a photo library by the cover designer, Ali Campbell. The three sisters discovered they were on the cover and came to my event at Brixton Library. The history of black British women is mostly untold, and they are part of our hidden history. I so enjoyed meeting them.

The novel was first published in May 2019 in the UK, by Hamish Hamilton/Penguin Random House, under the editorship of publishing supremo Simon Prosser, who had published six of my eight books with wisdom, sensitivity, and great skill for nearly 20 years before this breakthrough moment. I will always be deeply appreciative of his loyalty and guidance as an editor. The novel was published in November in the US, with the editor Peter Blackstock at Black Cat/Grove Atlantic, a new publisher for me, who, along with his colleagues, has expertly steered the novel onto several US bestseller lists.

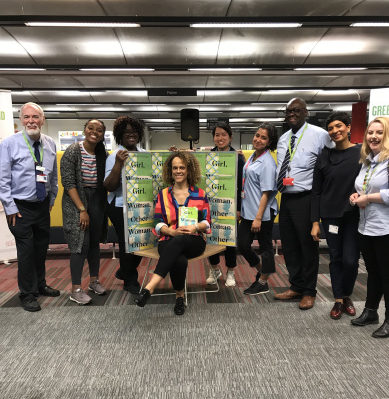

Public Events in the UK

As the Woolwich Laureate for 2019, appointed by Greenwich & Docklands International Festival and Greenwich Council & Partners, I spent a lot of time this year in the hometown I left in 1977, aged 18. (#espadrilles. . . .) During my reading at Woolwich Library, I was interviewed by Rasheeda Paige-Muir, founder of Revolyoutionlondon. Rasheeda is a Woolwich home girl, growing up a few streets away from my childhood home, and is one of the many young women I met this year who are actively being a force for good in the world. Her sister, Shani Paige-Muir, runs the Nyah Network Book Club, where I also did a turn.

I have since spent several days at Woolwich Library interviewing and recording local people talking about Woolwich: conversations which will inspire the “Woolwich Narrative” I’m going to write. Woolwich Library is amazing: it’s a community hub, a gathering place for all kinds of groups, a place where tutors teach children after school, a warm and safe space for people to get in off the streets, and it gives people who need them access to computers. There are lots of books there and it’s wonderful to see so many people sitting around reading them.

I ran some writing workshops for young people at Tramshed, formerly Greenwich Young People’s Theatre, where I spent my childhood acting in plays. I’m now one of their ambassadors. My still great friend J. from those days remembers me getting good parts at the youth theatre, but I don’t recall that at all. I wrote about the youth theatre for the Guardian.

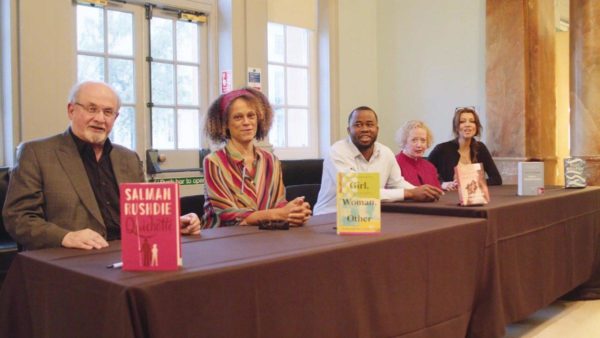

In October, I was at the Cheltenham Literature Festival with my fellow shortlisted novelists: Salman Rushdie, Chigozie Obioma, Lucy Ellman, and Elif Shafak. There was also an event at Southbank. Elif Shafak, one of the nicest and most supportive writers out there, was shortlisted for her haunting novel 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World. Several months after reading it, the story still lingers in my imagination.

In November, I was on a panel for the National Literacy Trust at Slaughter & May, with the Booker Prize literary director Gaby Wood, Malorie Blackman, Diana Evans, and Louise Doughty. And I was interviewed by Nydia A. Swaby at a Politics of Pleasure event at the ICA. In December, I was at the Black Girls Book Club Festival. Then I was at the first Words Weekend Festival, where I was interviewed by David Olusoga. Another highlight was being in conversation with Candice Carty-Williams (whose hit debut, Queenie, was published this year) for a BBC Radio 4 Front Row programme on Boxing Day, featuring just the two of us.

Literary Festivals in Nigeria

I have long travelled internationally as a writer, and this year I was invited to do events in Holland, Hungary, Poland, and, in October, the wonderful Ake Arts and Book Festival, run by Lola Shoneyin (also a brilliant novelist), and the Lagos International Poetry Festival (LIPFEST), run by Efe Paul Azino. At LIPFEST, I taught a fusion fiction workshop, and I was interviewed by Otosirieze Obi-Young of Brittle Paper, a conversation that covered my entire career. Both festivals took place in Lagos, where my father was raised.

It’s always special returning to Nigeria, and this time I took two of my siblings, who had never been before. Our father passed in 2001 but his spirit lives on, especially in Lagos, which was in his blood.

Recent Writing

Earlier this year, I wrote a somewhat lighthearted piece for The Royal Society of Literature pamphlet, A Room of My Own, alongside David Almond, Val McDermid, and Daljit Nagra, addressing the issue of what a writer needs to work. I wrote:

For about 30 years I was the Queen of Precarity, earning little and never knowing how the year would pan out financially.

This was indeed my reality. But I do accept that I chose a precarious profession, which for most writers brings creative fulfillment but little by way of financial return. A writer needs to build self-confidence and be self-motivated, and obstacles and set-backs develop these qualities if you don’t give up. The easy path doesn’t help artists build resilience, which, for everyone at some stage in their career, is essential to keeping going. I do think that after so long I am a testament to some of the most important qualities needed to maintain a career in the arts: ambition, determination, resilience, resourcefulness, and tenacity.

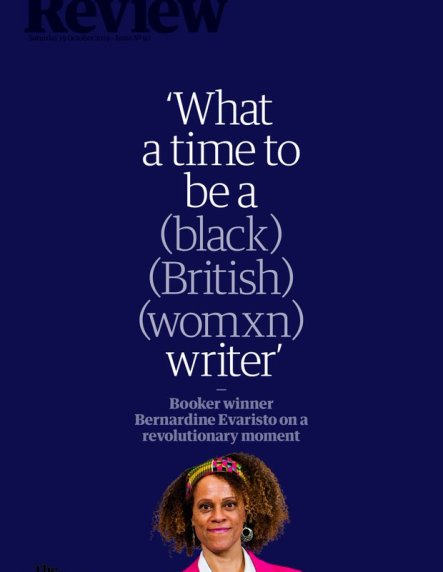

I have written many journalistic pieces and articles recently. An extract from my long essay, “What a Time to be a (Black) (British) (Womxn) Writer,” from Brave New Words (Myriad Editions, Nov. 2019), edited by Susheila Nasta and Mark Stein, was published in the Guardian. I contributed an experimental creative piece for Sam Winston’s The Dark Project, launching 2020. It involved spending a few hours in a blacked-out room in Hackney and then writing out of this experience. In October, I read a prose poem, “The Simple Life Cycle of the Islanders,” at the newly launched Museum of Colour, written for its Pitts River Museum Oxford collaboration. I also wrote a reimagined ending to Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway for BBC Radio 3’s “The Essay, Open Endings,” which was broadcast on Christmas Eve. And my “Top Books of the Year” choices appeared in six newspapers and magazines. More pieces are due out in coming months, including a short story commissioned and forthcoming in February.

I also contributed a story to New Daughters of Africa, edited by Margaret Busby and published 26 years after the first, Daughters of Africa, came out in 1994. Each anthology features about 200 (different) black women writers. What a feat, what a resource, what an encyclopaedia of our writing.

A lowlight was having a short story turned down, post-Booker, by a magazine which commissioned it and then decided it wasn’t good enough. Well, that put me in my place. I sent it to my harshest critics, telling them to be their usual brutal selves, and expected them to shake their heads in disappointment, but they all loved it. It was a savage satire, so maybe it misfired. Who knows? On the positive side, it’s good to stay grounded and rejection is very grounding. I’ll find a home for it somewhere.

Teaching at Brunel University

I rarely mention my other career in public, as Professor of Creative Writing at Brunel University London, where I’ve taught since 2011. This was a busy term for me, teaching several classes, tutor groups, and supervisions, and it was an incredible challenge post-Booker to maintain everything. But I felt duty-bound not to drop the ball with my students. It was very grounding (oh, that word again) for me to get up at 4 a.m. to mark-up students’ fiction homework in time for class later in the day, while a whirlwind of publicity and events gathered pace. I’d leave class, hop in a cab or get the tube from Uxbridge to central London, go off to do an interview or book signing, and then a public event, and arrive home at midnight, and then get up again at 4 a.m. to mark-up student’s work for the following morning’s class. I’m not quite sure how I held it together. Let’s just say that I’d almost curbed my caffeine habit pre-Booker, but I was soon back on five strong cups a day. I did 67 public events this year in the UK and abroad—readings, panels, talks—most of them in the second half of the year.

This autumn, two of my PhD students passed their vivas, subject to minor corrections, which is always an incredible relief for them and incredibly satisfying for their supervisors. After several years of intense doctoral study, they are soon to graduate as academic doctors. I also examined three external PhD candidates at other universities.

On Being Both a Writer and a Curator

Years ago, in the ‘90s, someone I knew, another black woman who was a powerful producer and had a sharp tongue, told me to concentrate solely on my own writing career and stop behaving like a “social worker” for other writers, because I’d never get anywhere. I had published two books and was working in literature development at the time, so her words stung. I’ve come across this sentiment since, although not put quite as brutally: that serious writers should stay focused on their own careers and not get distracted, by, for example, all the activities I generate and participate in. I don’t agree with this and winning the Booker Prize is proof that you can be taken seriously as a writer and be a serious activist involved in literature at grassroots level. It’s a choice, not an obligation.

I long ago chose to take my community with me on my creative journey. I grew up in a political family with activist parents who believed and fought for a more egalitarian society. When you are racialised and in various ways minoritised or marginalised in a society, you are also often not privy to the subterranean networks of power that support a status quo that is too often exclusionary. Individual success does not a sea change make. We need to be there for each other. We need to support each other. This is one of the many reasons why I loved Toni Morrison. We were at the centre of her universe and she never ignored or forgot us, which I highlighted in my tribute to her in the Guardian.

The Complete Works, the Brunel International African Poetry Prize, the African Poetry Book Fund, & Other Projects

One of my joys last year was to witness the ongoing success of The Complete Works poetry mentoring scheme (2007-2017). Ninety-five percent of the mentees have published poetry books, often more than one, and several of the 30 alums published new poetry books this year, including Raymond Antrobus, Mona Arshi, Jay Bernard, and Roger Robinson. Other alumni include Malika Booker, Sarah Howe, Rishi Dashidar, Kayo Chinonyi, Karen McCarthy-Woolf, Warsan Shire, Adam Lowe, and Eileen Pun.

In 2019, the Brunel International African Poetry Prize entered its seventh year, with joint winners: Nadra Mabrouk (Egypt) and Jamila Osman (Somalia). The 2018 winners were: Hiwot Adilow (Somalia), Theresa Lola (Nigeria), and Momtaza Mehri (Ethiopia). (As you can see, I don’t have a problem with prizes having multiple winners: #spreadingthelovebaby.) African poets are now proliferating and getting published and recognised across the globe. The Brunel University is the primary funder of this prize, and every year I work closely with Kwame Dawes, founder of the African Poetry Book Fund (APBF), on this and his prizes. I co-judge the APBF’s Sillerman First Book Prize for African Poets, and this year I was the sole judge for its Glenna Luschei Prize for African Poetry, which went to Koleka Putuma (South Africa), for Collective Amnesia.

I’ve further taken part in other projects this year, such as judging the LGBT+ Polaris Book Prize, which the novelist Paul Burston founded, alongside the monthly Polari Salon. The winner was Andrew McMillan, for his collection Playtime.

I’m currently cooking up another literature project advocating inclusion. My aim is to always place our under-told voices on the map: to help develop craft; to build careers and literary communities; to value our perspectives and validate our cultures; and to get our stories out there—taken seriously and read widely.

On New Black British Writing

I’m pleased to observe that an unprecedented number of black British books were published this year, many of them debuts, and I hope this momentum is sustained. I’ve provided puffs for many of these books and supported many others through reviews, mentions, and teaching them—nearly fifty books all told.

I’m aware that in 2019 I neglected established authors with new books I’ve been dying to read. As I progress into the New Year, I already have seven debut manuscripts waiting for me to provide quotes, just at a time when I really want to choose my own reading list. I will post on social media about books I’ve read and loved, and might even do this on Goodreads, but I need to spend time nourishing my own practice with books of my own choosing, and so I won’t have the chance to provide any more puffs for the foreseeable future. My aim this year is to read a book a week: fifty-two books. And I can’t wait. At the moment, I’m excited to read Minna Salami’s Sensual Knowledge: A Black Feminist Approach for Everyone and Paul Mendez’ Rainbow Milk.

My Next Book

I’ve had lots of ideas for a new book percolating in my head for most of this year, and I hope to sift through them and start writing it soon. Girl, Woman, Other, with its twelve co-protagonists and experimental fusion fiction, took five years to write and was a mammoth undertaking. I hope the next one doesn’t take as long, but I can never predict the length of time it takes to write a book—a book will dictate its own terms. I imagine that, as usual, there will be a lot of noise in my head while I’m working on the new project.

While I was writing Girl, Woman, Other, I was aware that my last book, Mr Loverman, had proved popular with readers, many of whom felt very affectionately towards it. What if everyone hates this new novel, I kept asking myself, while simultaneously reassuring myself, as I always do, that each new book will find its readers and that I have to write the book I have to write. I do expect that the noise inside my head for the new work will be louder than usual, and I will have to work hard at muting it.

The Truth about Books and Buzz

I began this year still tweaking Girl, Woman, Other, which was finally signed off in February and published in May. The industry is ever-evolving; since Mr Loverman was published in 2013, I’ve noticed that a big deal is increasingly being made of the media’s lists of “the most important and exciting books” to be published in the year. It felt, at this time last year, as if these books had been sanctioned as the only books worth paying attention to. Indeed, such lists are crucial for building hype around forthcoming titles, even though the books hadn’t yet been read, I imagine, and certainly not reviewed. I remember feeling disappointed that I only made two of these scores of lists. Why were media bods not excited about my book, I asked myself. I’m not at all a self-pitying person, and that moment quickly passed, but I want to register it here.

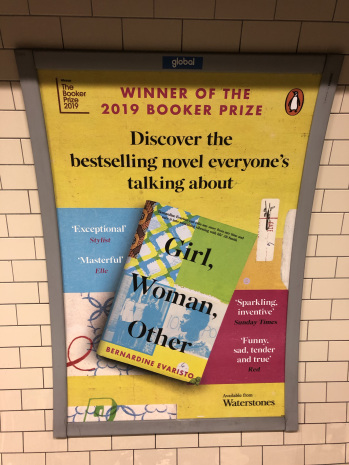

And then the rest of the year happened and, by the end of it, Girl, Woman, Other was on over twenty important Books of the Year lists, including several major Top 10s, the Sunday Times Books of the Decade list, and then, at the end of December, Barack Obama’s Favourite Books of 2019. What I really want to say to other writers out there is to not be disheartened if you don’t make these lists in the coming weeks, and to remember that social media is now a powerful space for you to share your work and engage with readers. We are no longer solely reliant on mainstream media to get our work out there. You also don’t know what’s going to happen with your new book—you really don’t. I’ll never get over the thrill of seeing a poster of the novel underground, another first in a year of personal firsts. People travelling around London sent me sightings of the poster in numerous tube stations.

I could never have predicted the journey of Girl, Woman, Other through the year, or my own emotional journey, which began in January with a degree of trepidation and “business as usual” and ended on such high notes. Winning the Booker Prize changed everything. I feel so blessed and give thanks. Don’t give up, writers, artists. If you love what you’re doing then keep doing it and keep improving your skills. We are powerful. Aṣẹ.

About the Author

Bernardine Evaristo, MBE, is the author of eight books: the poetry collection Island of Abraham, the novellas Hello Mum, Soul Tourists, and Lara, and the novels Mr Loverman, the Women’s Prize-longlisted Blonde Roots, the Arts Council Award-winning The Emperor’s Babe, and the Booker Prize-winning Girl, Woman, Other, a Sunday Times bestseller. She is the founder of the Brunel International African Poetry Prize and The Complete Works. A Professor of Creative Writing at Brunel University, she is currently Vice Chair of The Royal Society of Literature.

About Poets: BERNARDINE EVARISTO - a śort spel June 03, 2023 14:46

[…] TELEGRAPHBLOODAXEBRITISH COUNCILBRITISH LIBRARYBRITTLE PAPERDESERT ISLAND DISCSECONOMIST*EVENING STANDARD*FT*GOOD READSGRANTAGUARDIANHERALD […]