TW: abduction and sexual assault

Papa’s death was one of the two defining events of my childhood. The other was the day I was kidnapped. We later learned that my abductor was accused of murdering several boys my age.

There is something to be said for cheating death. The ghosts are intrepid. They will not go away. When you are a child, of course, you have no language for the haunting. Now, I have a name for it, but still, it does not go away. It shows up at school, at work, in dreams. It shows up at night. Oh yes, it loves solitude. It flourishes in the dark, in the dim corners of your mind, places where it is dank and airless. “You should not be here,” it whispers. “You are going to die. I am simply biding my time.”

Even now, there’s some dispute as to what happened, whether the man who took me from my home on that day in ‘85 was truly a serial killer. He was so kind, some people said. Besides, they only convicted him for one of the murders. Some went as far as accusing the authorities of a political ploy to pacify the electorate before the ‘94 elections. Even during his trial people showed up to plead his innocence. Such a nice, quiet man, one woman said. He had visited her house many times and taught her sons Bible lessons. The mothers of the victims endured the deaths of their sons and were then made to endure the anguish of the speculation. Many of them died with the murders of their sons having been reduced to a whodunit. For years, journalists agonised over the events that occurred over that decade. What really happened? If it wasn’t him, who really killed all those boys?

But I remember. I remember.

I remember the grey of the clouds on the day it happened. I remember his face, his voice, and everything up to that moment: the colours, and the confusion. I remember the moment I lost control of my body. My body my body. I don’t know when it felt like my own. I don’t know when last it felt like home. Something rarely shared.

I remember it like I remember bathing in a zinc tub in the kitchen of our house back then, sharing the bathwater with my cousins. I remember it like the sound of the embarrassed cockroaches scurrying out of sight when we switched on the fluorescent light in the kitchen. Like the smell of my uncle’s Mum for Men deodorant wafting through the house as he got ready to go out on a Saturday night. Like the eyes of fathers coming home on a Friday night, drunk and proud, with a fish parcel under their arms, a gift to their expectant children and indignant wives. For one night, they could be spared the effort of cooking. The salty food, with its rich flour-and-buttery batter, was a prize that the breadwinner had earned for his family, along with his 50 rand in wages for that week. “Daddy, did you bring us something nice?” the children would ask, knowing the answer.

I remember the terror I felt for years after that day whenever my mother went out of my sight. Shopping trips often became a dramatic scene when she gave me the universal maternal instruction, “Wait for me here. Don’t move.” Within minutes, I would imagine all sorts of nightmare scenarios of abandonment. At times, I even sought out the store security, in tears, to report myself lost.

I remember it like I remember my mother telling me at night before bed, “Do you know how many stars there are in the sky, and how many grains of sand there are on the beach? Infinity times infinity,” she would say. “That’s how much I love you.”

Just like the names and faces of our neighbours. I remember.

By the time we moved there, six years after the youth uprisings in Soweto and three years before our first state of emergency, researchers were already describing our neighbourhood as overcrowded. The Group Areas Act had made refugees out of us, forcing families to give up the mountain and the ocean for the sand dunes and alien vegetation of the Cape Flats. We fell into that category. Except, for us, the township where we landed was an upgrade from the nomadic existence my mother and her siblings had become accustomed to, relying on family to provide them with shelter after they fell on hard times. Often this amounted to a tin shack that they were allowed to install in someone’s backyard. My mother remembers how her shoes would float off the floor when water flooded their shack in the rainy season.

Our four-room council house in Bream Way, Nooitgedacht, was a bizarre clash of conflict and seam-bursting joy. We crammed into it, along with seven adults and four children, as many laughter-filled birthdays and Christmases as we could. Our rituals were chicken roast lunches on Sundays, violence on Saturdays, and holidays that included half the neighbourhood. Each year, around 15 December, when the factories shut down for the festive season, our backyard became a gathering place for family and friends. Even the factory girls who worked with my grandmother and aunt would join the celebrations. They would sleep on the stoop outside our backdoor when parties spilled into the next day. It was a high-octane existence. Everything was loud. The laughter was loud. The loving was loud. The larceny was loud.

Next to crime, being lazy, unemployed or underemployed, were considered the worst offences in my family. You could become an outcast for being any of those. You certainly weren’t deemed a respectable adult. And the one thing that separated us from animals was the level of enthusiasm with which we acknowledged our fellow man, especially elders. “She could have kept her greeting,” the old people would say. It was how we measured our humanity. And we held that view with the same ferocity as initiation rites in other communities. High on the list of serious contraventions was neglecting your children, which could mean being a no-good drunk or not dressing them in a decent winter coat or shoes, or having your offspring seen in public with a runny nose. Because you don’t raise your children for yourself. You raise them for other people.

When the children started disappearing, community leaders blamed the parents and socioeconomic conditions. The first body was found about a year after I was abducted. He was buried face down, strangled, with his hands tied. Like the other young boys, his body was discovered close to a train station. All of the children were found within a fifteen-kilometre radius, stretching from the bushy flats where we lived to the sand dunes of Mitchells Plain. In total, there were twenty-two victims. The youngest was six years old, the oldest thirteen. At least those are the ones we know about.

Sometimes weeks would go by with no news of another young grave, and parents would heave a sigh of relief. Perhaps the nightmare was over, they thought. But then the evil reared its head again. In no time at all, we became an anthropological case study. One foreign newspaper even compared the murders to the political killings of the time. It was a savage reminder that most murders in South Africa are political, it said. To shield their children from harm, parents kept them out of school, and they formed vigilante groups in their neighbourhoods, armed with pangas and whatever other weapons they could find. Hernus Kriel, the Minister of Law and Order, visited Mitchell’s Plain and announced a reward of 250,000 rand for information that led to the killer’s arrest.

Now and then, a memory of that period finds its way into my dreams. Sometimes it’s a sensation more than an image. The texture of the soil, perhaps, or the tone of his voice, unattached from his face, purely sound and inflection. As I write this, I am marooned in my hotel room in Abidjan, watching the lagoon float by from my third-floor window. It’s been months of not seeing family or friends, and no idea when a reunion will be possible. The smell of fried fish and tomato and onion salad lingers on the table behind me, where my lunch leftovers are waiting to be collected by one of the staff. I look at what I scribbled in my notebook yesterday.

20 August 2020

Loneliness is the root of all evil.

A few days ago, I was sitting at the same window, absorbing the latest news about the pandemic. I thought about the pile of work taunting me from my laptop, and the futility of trying to piece together parts of speech when the world was falling apart.

Most of all I thought about home. What would I return to when I could eventually go back there? Would my loved ones be waiting for me, or would I be orphaned? One after the other, these thoughts sped through my head, until eventually they flailed in every direction and collided hopelessly into each other. I felt a surge or a jolt of some kind and blacked out. “When was the first time I felt like this?” I asked myself as I recovered minutes later.

It was that day, I thought. It was that day.

It must have been August or September, one of those wintry months in the Cape, because the ground was wet. Until recently, the streets were almost impossible to navigate. Even as Spring beckoned, tendrils of cold hung in the air. We would have to wait a few more weeks for the southeaster to launch the warmer season. All these years later, without fail, the streets are still rendered impassable after a few days of rain.

“It’s been happening since this place began in ‘68,” a friend told me this year as the water encroached into some of the houses in the neighbourhood. Patients were turned away from the community hospital because nurses were unable to get to work and schools closed early so parents could collect their children before the flooding worsened. The invasion of the water was like a weeping of the rivers that used to flow here before they were herded into canals, much like the people who were forced to move here against their will.

Nevertheless, it was around that time of year that I had my narrow escape.

I remember the tracksuit I was wearing that morning, and auntie Barbie, our neighbour, shouting at me and my cousins over the shoulder-high mesh fence that separated our front gardens. We were playing with our pretend cars in the dewy soil. The make-do toys were red bricks we had found lying around in our yard or somewhere nearby. We turned the bricks on their sides, with the long, narrow ends of the rectangular objects serving as bottoms and tops of our imaginary buses. For passenger cars, we used the wider surfaces. The sound of the bricks swishing through the soil was soothing, and so were the neat grooves they traced through the Nooitgedacht earth.

“Get off that sand,” auntie Barbie ordered us. “You going to catch a cold.” We jumped up as auntie Barbie yelled, not even looking in her direction. There was no time to waste when it came to obeying adults. As soon as she was satisfied that we had obeyed her, auntie Barbie turned around and went back inside her house after collecting the milk on her stoop. When we were certain she was safely inside, we went back to our deeply satisfying game.

“Beep-beep!” we shouted when our paths crossed. Other times, these traffic jams would lead to conflict, but today we were just too happy to be together.

It was school holidays. Shane, Chad and I were too young, but Nathan had started primary school that year. Nathan was two years our senior and the eldest of our quartet, in addition to being tall and strong. Even at that age, he already held dominion over us. It was a privilege to be in his company, especially now that he had joined the ranks of the school-going.

“Good morning,” a friendly voice said from the other side of the fence. Before any of us could answer, the man continued. “I’m looking for Mrs Isaacs’s house.” He was tall with a deep-brown complexion and thick hair, styled in what we called a curly perm those days. I was probably the first to answer, being precocious.

“It’s over there,” I pointed to a house three or four doors down on the opposite street. He seemed not to see where I was pointing. “I’ll show you,” I said, leaving the yard to walk with him.

“Liam, come back here,” Nathan commanded.

“I’m coming now,” I replied dismissively, determined to show that I was just as worldly as he was.

“Here it is,” I said as we reached the house in question.

The man gripped my arm, with just enough force, and said, “No, that’s not the house I was talking about.”

I went along with him, puzzled but eager to be helpful. At some point, he proffered a packet of NikNaks, placating me somewhat with one of my favourite snacks. We turned right into Barracuda Crescent, then took another right into Kasteelberg Road, along the streets with nice houses, lush trees and prim hedges that greet you from behind vibracrete fences decorated with friendly patterns, similar to the ones children are taught in school when they are first learning to write. These houses were actually occupied by nuclear families of four, not like ours, where even the kitchen served as someone’s bedroom.

The further we walked, the more our pace quickened, and so did my asthmatic breathing.

A few steps, and then gasp, gasp. Fine droplets of sweat formed on my forehead and the backs of my knees as I tried to keep up.

Gasp, gasp. A few more steps.

Gasp, gasp, gasp.

We reached our destination. Not 10 minutes from home. The place where I faded into this drifting thing that I’ve become. It was morning, but probably past peak-hour traffic, because he managed to guide me unnoticed across the busy main road and into the nearby bushes. The ground was thick with untended leaves, and they cracked underfoot as we stepped into the vegetation. After walking ten or so steps, we stopped. He asked me to turn around and pulled down my pants. He pressed himself up against me, and I froze. What was happening? My confusion turned into fear.

“My child, my child!” it was my mother. Her screams echoed through the streets. “Stop it!” someone reprimanded her. I tried to break free but he gripped me and held his hand tightly over my mouth. “Shush,” he said. “It’s okay.” The commotion grew.

“Liam! Liam!” other voices shouted.

Realising that they were closing in on him, my captor fled, while I ran towards the sound of my mother’s voice. I found her in a nearby street, being propped up by my aunt, and trailed by a search party of neighbours. I can’t remember my first words or what I did in that moment and the days that followed. But I do remember the sense of relief I felt when I was reunited with my loved ones.

Somehow, they had found me. By then, the sky had cleared, and I was golden again. Only a faint trace of clouds clung to the dome of my five-year-old sky.

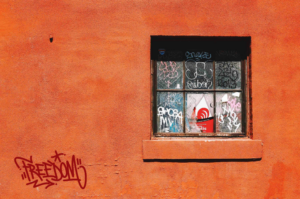

Photo by Jakob Owens on Unsplash

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions