Fiston Mwanza Mujila was announced winner of the 2015 Etisalat Literature Prize at a grand ceremony in Lagos on March 19, 2016. As Chair of the Jury panel, which also included writers Molara Wood and Zukiswa Wanner, I was proud to make the announcement at the ceremony and to bask vicariously in the glow that surrounded him. The Jury recognized the book for its great humour, its experimental narrative style, its adroit characterization, and for the subtlety of its reflections on the state of African politics today. What I propose to do now is to set this startling first novel in the context of African and world literature.

The novel revolves around the fraught relationship between Requiem, an all-round hustler with a predilection for the oracular, and Lucien, a down-and-out historian and writer struggling to find his métier. Lucien is dependent on the largesse and support of his erstwhile friend and now reluctant benefactor. The story of the two friends is interwoven between two settings, one more prominently situated in the foreground and repeatedly returned to as the privileged confluence for all the major characters—the Tram 83 of the title—and the other the political and social setting of the City-State.

The City-State is a misshapen republic that has broken away from the the equally allegorically named Back-Country. Both are barely concealed references to the Democratic Republic of Congo, the City-State being the province of Katanga famous for its rich deposits of minerals including diamonds and cobalt, and the Back-Country being the rest of the DRC. The designation of the City-State is highly suggestive, as it points to the fact that it is neither a fully-fledged city nor is it an operational nation-state. Rather, its in-between status allows Mujila to paint an unsettling picture of brutal political self-interest placed at the mercy of a marauding capitalism.

Capitalism in the novel is firmly tied to resource extraction and is depicted in the novel by the many international tourists that mill about the place and always end up at the Tram. The name tourist is itself an ironical play on a commonly used designation of leisure and discovery, for the many transnational tourists of Tram 83 are no sightseers but rather intent on expropriating heterogenite, the word coined in the novel as a stand-in for the numerous minerals that the province has been known for in the course of its turbulent history. As we are told: “The region was so rich in deposits that a legend had grown up—and it happens to be true—recounting how the inhabitants of the City-State dug up their gardens, their houses, their living room, their bathrooms, their bedrooms, and even the cemetery. Yes, in the cemetery funerals would sometimes turn festive following chance discovery of a high-grade stone.” 1885 is frequently referred to in the novel as the year in which the tourists began to arrive in this veritable El Dorado, but those familiar with the history of the region will recognize it as a signal of the start of Belgium’s colonial rapine of the Congo following the 1884-85 Berlin Conference, when thirteen European countries and the United States met to settle the rules for Africa’s colonization. The precarious political status of the City-State in relation to the Back-Country also means that as their self-appointed messiah, the City-State’s Dissident General is emboldened to pass numerous edicts aiming to fortify its political independence and, more pointedly, to generate wealth for lining up his own pockets. The citizens of the City-State, the tourists, and everyone else are in permanent thrall to his every whim and caprice.

The foreground and background settings of the Tram and the City-State provide two different yet interlinked dimensions for interpreting the novel. The fact that the City-State spells political oppression, obscene consumption, the free-reign of greedy transnational capitalist interests, and decrepit social conditions for the many encourages that we read the novel at least in part as a political allegory reminiscent of some of the work of Ayi Kwei Armah, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Sony Labou Tansi, and Ngugi wa Thiongo, among the many other African writers that have turned to the subject of politics in Africa. As setting the Tram on the other hand is a cross between a nightclub, a circus, and a theater of dreams. As we are pointedly told on the very first page, “indeed, an air of connivance hung ever about the place”. This air of connivance turns out not to be an idle metaphor, for whenever we are ushered into Tram 83 we eavesdrop on various deals-in-the-making, some with potentially sinister consequences, as we later come to find out. The various deals include the Belgian tourist Malingeau’s proposition to Lucien for him to scale down the number of characters in his working play so he can get him published, Requiem’s incessant interventions to either prevent the book deal from happening, or if it does, for him to exclusively profit from it, or, as we see repeatedly throughout the novel, the baby-chicks’, single mamas’ and busgirls’ attempts at attracting the club’s male clients. As we shall see in a moment, the female sex workers’ repeated attempts at getting the attention of clients in Tram 83 and the “psalms” that they reel out as part of their seductive repertoires provide re-iterated refrains that establish an unusual rhythmic quality to the narrative.

There are many ways in which Tram 83 is likely to be read, but I want to surmise that all of them will have to involve some reference to music. Jazz and other kinds of music infuse the nightclub without fail. Each time we are ushered into it we have the benefit of a band playing and are given elaborate descriptions of the provenance of the bandsmen (they come from various parts of the world, including South America), the sources of their music (a medley of jazz, salsa, Zairean-infused rumba, and several other music types), their playing styles (good, bad, and plain mournful), and even of the clothes they wear. We are also regularly shown the club audience’s responses to the various bands, ranging from indifference through excited approbation to menacing hostility. But the musicality that we see at the level of content is also superbly augmented by rhythms at the level of narration and it is here that the experimental innovativeness of Mujila’s narrative style is likely to be recognized. The rhythmic character of the narration is systematically structured around a series of repeated sentences, phrases, and sequences in a sometimes harmonious but often dissonant distributional matrix. These provide the novel not only with the air of an improvisational jazz symphony, but, perhaps even more importantly, lend it a dramatic character, as if it was written to be visualized rather than just read, or for stage and screen, rather than just for the inert pages of the book we hold in our hands. There is something even danceable about it.

There are reiterated elements that contribute to the rhythmic sense of the narration. One is to be found in the subtle relationship established in the novel between ensembles and solos, or in another register, a chorus function and that of individual performativity. This particular feature is itself amenable to a musical interpretation, such as in examples of scene-setting at the beginning of a chapter 14:

Tram 83, interior.

In the background, a saxophonist performing a solo.

Center-forward, the young ladies of Avingon in their vestal robes eyeing up all the masculine clients.

Left-back, the Chinese tourists.

Front door, the busgirl with fat lips and her colonial-infantry patter (85).

Or, in a more pointedly operatic mode, the reaction (predominantly skeptical) to Malingeau’ first introduction of Lucien to the regulars of the Tram as a historian:

“Dear friends, you’re not going to believe me: this man you see is a historian!”

General hilarity.

The whole Tram as one:

“Didn’t you give a shit, or what!”

Then as a scattered choir:

“And you earn a living doing history?”

“Look what can happen by dint of imitating the tourists!”

“You study girls too, or just history?”

“You’re an embarrassment to us, with your wallowing in art history!”

“I’ll throw myself onto the tracks if dad insists I study history and stuff,” exclaimed a kid, barely ten years old, who was with his father.

. . .

“You can’t do anything about a passion. But I’m not just a historian. I’m also a writer.”

A guy at a neighbouring table butted in:

“Writer or historian, same difference.”

“I’m in writing,” he insisted.

“Writing. Writing. Writing.

His interlocutor pronounced this word in a guttural voice. He remained circumspect, as if victim of an apparition. Lucien remained on his guard, for fear of being made a fool of a second time.

“I’m a write but. . .” (42; 43).

And, about twenty pages later, a reprise, but this time as Lucien attempts a public reading of his manuscript, suggestively titled, by the way —The Africa of Possibility: Lumumba, the Fall of an Angel, or the Pestle-Mortar Years:

He extracted his texts from a portfolio. He took a serious stance. He opened the ball after having requested a minute’s silence in memory of the victims [of a recent mine cave-in]. He was trembling like a dead leaf. He emphasized the words, raised his voice. He hadn’t counted on the audience trying to trip him up. One minute too many, one sentence out of place, and he’d find out what they were made of. Which wasn’t long in happening, as the imprecations began to rend the heavens.

The whole Tram, as one:

“Get off, Lucien!”

Then as a scattered choir:

“Don’t you preach at us!”

“You’re hot, I want you!”

“Alligator!”

“Show-off!” (61)

One can almost hear the dissonant acapella captured in these scenes. The entire novel can be read along the lines of an opera or a ballet, for almost all the conversations that take place are set against the distribution of characters within the scenes in a variety of clusters that establish different relations of proximity and distance to the events that unfold. Mujila’s consistent infusion of music into his narrative calls to mind most strongly Wole Soyinka’s own deployment of drumming throughout the action of Death and the King’s Horseman. Soyinka’s play has a highly elaborate sonic and poetic dimension that is easy to miss when reading it merely as a play text. But whereas Soyinka’s sonic infusions provide a means of modulating the action of his play, in the case of Tram 83 the musical dimension is a means of suggesting an orchestration, as if Mujila is the conductor of the improvisational jazz symphony I mentioned earlier. This dimension of orchestration (and not just the presence of music at the level of content) seems to me to be distinctive in African if not world literature.

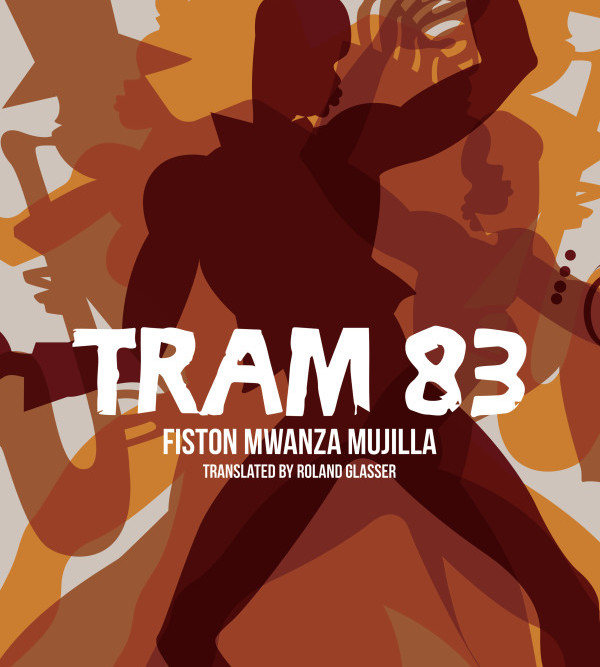

* Tram 83 was superbly translated from the French by Roland Glasser and published by Deep Vellum Publishing in 2014.

************

About the Author:

Professor Ato Quayson is Professor of English and inaugural Director of the Centre for Diaspora Studies at the University of Toronto. He studied at the University of Ghana and the University of Cambridge and was also a Fellow of Pembroke College, Director of the Centre for African Studies, and on the Faculty of English at Cambridge. He was the 2011/12 Distinguished Cornille Visiting Professor in the Humanities at the Newhouse Centre at Wellesley College; he held research fellowships at Wolfson College, Oxford (1994/95) and at the Du Bois Institute for African-American Studies at Harvard (2004). He is a Fellow of the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the Royal Society of Canada.

Professor Ato Quayson is Professor of English and inaugural Director of the Centre for Diaspora Studies at the University of Toronto. He studied at the University of Ghana and the University of Cambridge and was also a Fellow of Pembroke College, Director of the Centre for African Studies, and on the Faculty of English at Cambridge. He was the 2011/12 Distinguished Cornille Visiting Professor in the Humanities at the Newhouse Centre at Wellesley College; he held research fellowships at Wolfson College, Oxford (1994/95) and at the Du Bois Institute for African-American Studies at Harvard (2004). He is a Fellow of the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the Royal Society of Canada.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions